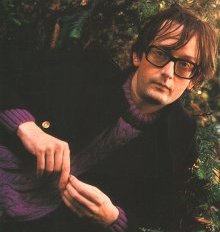

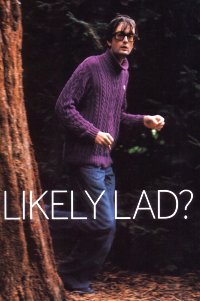

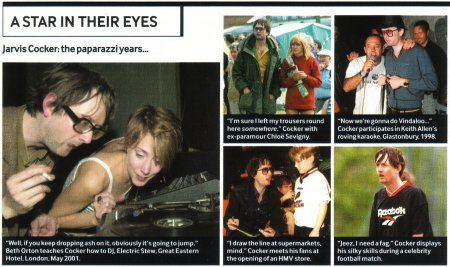

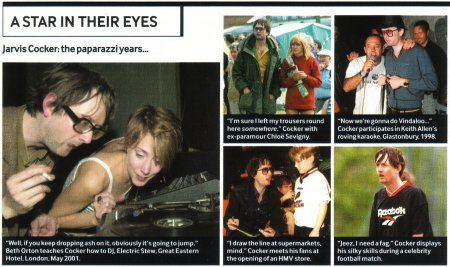

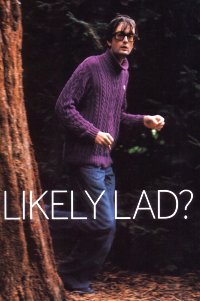

Whatever Happened To The Likely Lad?

Whatever Happened To The Likely Lad?

Words: Steve Hobbs, Photographer: Chris Floyd

Taken from Q Magazine 183, November 2001

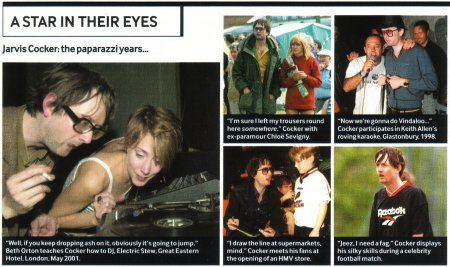

Once upon a time, Jarvis Cocker was Britain's best-loved proletarian. One "moon" at Michael Jackson later, it was hola paparazzi, hip Hollywood girlfriend and non-selling drug album. Sobered, and three years on, Cocker and Pulp are back, with a thumping fame hangover and a day return to the country.

Pulp, it seems, are running away - though on this particular September afternoon they haven't got far. Still, they glean some comfort from London's cultivated equivalent of the Great Outdoors. "This is the imaginatively named Big Tree," says Cocker, pointing in the direction of a wooded glade as he strolls briskly through Kew Gardens. "I heard about it on Radio 4. It's as old as the dinosaurs. That's why the branches start up so high - to stop the brontosauruses eating them."

Fascinating though this nugget of information is, it does little to lift the mood among the bedraggled remainder of the group, sheltering from the cold autumn drizzle. Poor, petite keyboard player Candida Doyle - dressed in a home-knitted patch work cardie and, quite literally, old school trainers - has turned the colour of her pale blue summer dress. Only guitarist Mark Webber, in his sensible scarf looks content.

Right now Jarvis Cocker is into nature. The new Pulp album, titled We Love Life, includes tracks called Weeds, Sunrise and Birds In Your Garden. Trees are the subject of the band's first single, The Trees, in three years. He's even growing "a bonsai fig tree" in his tiny Hoxton garden which, with a typical Cocker flourish, he took as a cutting from the graveside of author William Blake.

"I never took any notice of nature when I was a kid," he says. I thought we'd all be living on space stations or floating metropolises by now. But after This Is Hardcore, which was a very alienated record, it was time to go back to simpler things, like this, the natural world." He waves vaguely at the rows of ornately trimmed flower beds and carefully maintained green houses. Then he laughs. "Only this is better because everything is labelled."

There has been some concern of late regarding Jarvis Cocker's state of mind, speculation fuelled, in part, by his continually changing social circle. After Pulp's post-This Is Hardcore live return at Reading Festival last year, talk of a new album dissipated. There were dark rumours of dissent in the ranks and that an album's worth of tracks that had been jettisoned. Worse, Cocker's new Hoxton life, which necessitated rubbing shoulders with the artistic likes of Tracy Emin, seemed to be turning his head. Then there was the high profile fling with Hollywood actress Chloe Sevigny which, combined with the bleak soundscape of This Is Hardcore, seemed to signal the last days of disco, as far as Cocker was concerned. A DJing set at a Chanel party during last year's London Fashion Week followed, as did an appearance in the social pages of unCommon People's monthly, Vogue, with stylist Camille Bidault-Waddington.

Next up came involvement in a Channel 4 series about Outsider Art, and the recruitment of '60s recluse Scott Walker to re-record Pulp's scrapped album. Performances such as the Touch Of Glass collaboration with Pulp bassist Steve Mackey and a glass harmonica player at Walker's Meltdown Festival did little to change the popular opinion that Cocker had disappeared somewhere up his own upper colon. Even so, artiness we could forgive. After all, Cocker did study film at St Martin's College and, even during his brief brush with Vogue, still dressed himself like a particularly down-at-heel student. But now, with the continual talk of nature and the desire to get back to basics, new whispers surfaced: that pop's favourite working class cynic has traded in his glorious sneer and become - god forbid - a hippy.

Next up came involvement in a Channel 4 series about Outsider Art, and the recruitment of '60s recluse Scott Walker to re-record Pulp's scrapped album. Performances such as the Touch Of Glass collaboration with Pulp bassist Steve Mackey and a glass harmonica player at Walker's Meltdown Festival did little to change the popular opinion that Cocker had disappeared somewhere up his own upper colon. Even so, artiness we could forgive. After all, Cocker did study film at St Martin's College and, even during his brief brush with Vogue, still dressed himself like a particularly down-at-heel student. But now, with the continual talk of nature and the desire to get back to basics, new whispers surfaced: that pop's favourite working class cynic has traded in his glorious sneer and become - god forbid - a hippy.

So, while Cocker is spirited away by the photographer to hug a few more trees, the rest of Pulp seek refuge from the cold, and recount events since Reading Festival's false dawn, some 18 months ago. "Reading was a dodgy point," remembers Doyle. "We had started an album with Chris Thomas [Different Class and This Is Hardcore producer], but it hadn't worked out and, despite trying several different producers, nothing was happening. There came a point when we were thinking, Christ, why bother?" So Pulp came very close to calling it a day?

"I certainly thought about leaving," adds Doyle. "But I realised that I'd still feel shit even if I did. If Scott Walker hadn't come about, I don't think we'd have bothered to finish this LP."

Pulp first hob-nobbed with Scott Walker in the summer of 2000, when Cocker was asked to appear at the artsy Walker-curated Meltdown Festival on London's artsy South Bank. Together with Mackey he performed a set which the softly-spoken bass player now describes as "disastrous". "When Scott came into our dressing room afterwards, I just hid," Mackey remembers. "So when he called a few days later and said he wanted to produce our album I didn't know what to think. I'd never considered working with him."

But Walker had been a big influence on early Pulp recordings. Cocker in particular had always been a fan so, despite reservations, the band agreed to give it a try. As Doyle says, "The choice was that or not get the record done." Perhaps the vacillation over recording stemmed from Cocker's fear of failure following the unevenly received This Is Hardcore. Drummer Nick Banks certainly thinks so. "There were times when it was very difficult to get Jarvis to make any decisions," he says. "But once Scott was on board it was obviously not an opportunity to be missed."

Mackey agrees. "Jarvis has certainly been very variable over the last year. He's been having this fight with himself about only doing things he enjoys. That has meant saying no to people, but it has made his life a lot easier." While age may have augmented Cocker's desire to have a more serious outlook on the future of the band and his career, this is, lest we forget, still the man who pointed his arse in the direction of Michael Jackson during the Brit Awards in 1996. "Ultimately, I have difficulty thinking of Jarvis as a pop star now," Steve Mackey smiles. "There was a time when he definitely was one. A celebrity even. But not now. Although he'll probably hate this, he's much more of an artist these days." Well, forewarned is forearmed.

Later, Cocker seems neither relaxed nor particularly happy. The photoshoot has overrun and he is now late for an appearance on Radio 2. Besides, he says, he is tired and pessimistic today. The recent US terrorist attacks have left him with a feeling of creeping dread which has been keeping him awake at nights. He folds his lanky 6'2" frame into the back seat of a surprisingly cramped family car, carefully hooking his knees behind his ears. It was a basic need of mine after Hardcore to go back to basics in some way," he says, explaining the modest choice of vehicle.

"To slow down and try to find some meaning in life. A lot of people grow up thinking that stardom will do something for you and solve a few problems, but that's not true. You have a basic human nature that won't be solved by fame. No one ever says, Before he was famous he used to be such a prick, but now he's quite nice. Fame usually has a negative impact on people and I was aware that it was happening to me. I had to find some way of stopping that. In my dealings with other people I was becoming difficult," he adds carefully, as the car heads towards the BBC studios. "Your ego gets inflated and you start to see other people as items of consumption. You have to make sure that the reasons you have relationships with people are the right ones. It's easy to get into relationships as a career move. I don't think I got that bad, but you do wonder about your motives sometimes."

The incongruous images of Cocker and Hollywood starlet Chloe Sevigny that caught the attention of the tabloids during their brief relationship last year would suggest that this was the case. Cocker sighs and shakes his head. "I don't talk about my personal relationships," he says quietly. "Chloe just didn't work out. You can't ever say why and anyway, it's crap to think about yourself that much. I didn't like New York [Sevigny's home] very much. You can't get lost there, the street system is too logical." Cocker returned to London, but the paparazzi attention became too much. By way of therapy he started taking himself off for long walks and bike rides into the countryside to hide.

"I was attracted to the countryside and nature because it is dangerous in some ways," he says. "I knew fuck-all about it and wanted to learn a bit." It's a new outlook that sounds disturbingly like the manifesto of a new age traveller, or worse, a fell walker. Cocker vehemently disagrees. "This isn't Pulp's pastoral album," he scowls. "I was very aware of avoiding hippy dippy stuff. Weeds is not a nice song; Sunrise may be the most noisy terror tune ever recorded. I'm screaming about my life and I certainly don't want it to end. You have to fight to the death for the right to live your life. As soon as you stop making any effort then your life fucks up."

Making more of an effort is important to Cocker now. Maybe it was getting into the year 2000 and, despite his lyrics, finding he hadn't fully grown. It certainly bugs him that he is still, to many, the bloke who mooned at Michael Jackson. Even so, he denies suggestions that he's currently reinventing himself. "It's such shit to talk about reinventing yourself because no one does," he says. "My problem is I never chuck anything away, that's why my house is such a mess. But I had to bin off some of the more flippant sides of me. Not that I want to become a boring bastard, but I didn't need to be such show off anymore."

Change is a strong theme running through We Love Life. From the adapt-and-survive ethos of Weeds to the wistful retracing of a long-dead Sheffield love affair in Wickerman, Cocker's lyrics are still sharp and beautifully observed, just a little less personal. But in many ways, it's a more familiar Pulp record than This Is Hardcore. The spiky discord has been replaced by lush, soaring strings and Walker brings a live languidness to the record which Pulp have not had since their earliest albums.

"I think anyone who listens to the album will know it's us within the first 20 seconds when my shitty voice comes in," says Cocker. "Hardcore was made against all the odds when we were going through bad times. This record is back to a more-healthy state. You need to do different things to keep your mind alive. Like me and Steve have our DJing with Desperate, Mark has film. Music is a product of your life, not a substitute. Life first, creation second. That's how it works."

So, does that mean we can expect Pulp to turn into some kind of arts collective, a Sheffield Wu-Tang Clan that comes together occasionally for a variety of projects? "I don't think so," Cocker says, shaking his head. "You sound like such a c**t if you call yourself an artist. I just like the idea of people doing things." As the car turns into the BBC studios, Cocker unfolds himself from the back of the car and starts chuckling to himself. "I like the idea of being a Sheffield Wu-Tang though," he laughs. "Especially if I can be Ol' Dirty Bastard." With that he is ushered away.

Jarvis Cocker, a changed man? Sort of.

Whatever Happened To The Likely Lad?

Whatever Happened To The Likely Lad? Next up came involvement in a Channel 4 series about Outsider Art, and the recruitment of '60s recluse Scott Walker to re-record Pulp's scrapped album. Performances such as the Touch Of Glass collaboration with Pulp bassist Steve Mackey and a glass harmonica player at Walker's Meltdown Festival did little to change the popular opinion that Cocker had disappeared somewhere up his own upper colon. Even so, artiness we could forgive. After all, Cocker did study film at St Martin's College and, even during his brief brush with Vogue, still dressed himself like a particularly down-at-heel student. But now, with the continual talk of nature and the desire to get back to basics, new whispers surfaced: that pop's favourite working class cynic has traded in his glorious sneer and become - god forbid - a hippy.

Next up came involvement in a Channel 4 series about Outsider Art, and the recruitment of '60s recluse Scott Walker to re-record Pulp's scrapped album. Performances such as the Touch Of Glass collaboration with Pulp bassist Steve Mackey and a glass harmonica player at Walker's Meltdown Festival did little to change the popular opinion that Cocker had disappeared somewhere up his own upper colon. Even so, artiness we could forgive. After all, Cocker did study film at St Martin's College and, even during his brief brush with Vogue, still dressed himself like a particularly down-at-heel student. But now, with the continual talk of nature and the desire to get back to basics, new whispers surfaced: that pop's favourite working class cynic has traded in his glorious sneer and become - god forbid - a hippy.