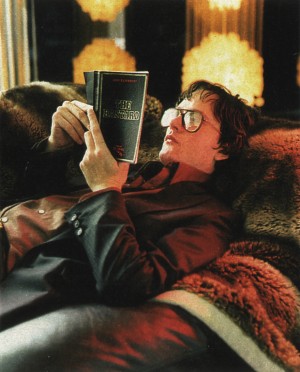

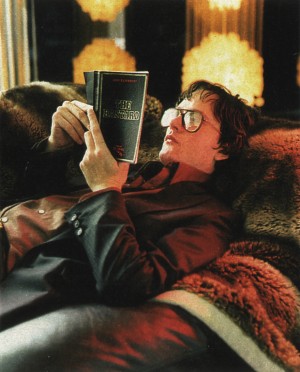

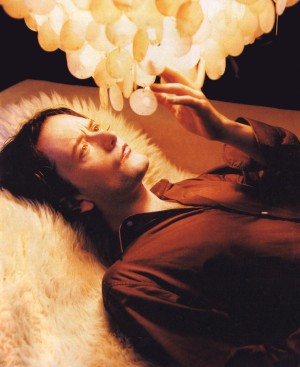

Words: Dylan Jones, Photographer: Richard Croft (On location at Peter Saville's Flat)

Taken from The Sunday Times Magazine, Spring 1998

Vic Reeves has called Jarvis Cocker 'the weed in tweed'. But is he also Britpop's poet laureate?

My heart was pounding so loudly I was convinced the auctioneer could hear it. After all, he was only 6ft away. In a matter of minutes the bidding had already reached £1,200 and, having set myself a ceiling of £1,000, I was obviously way over my limit. But still I carried on.

It is not often I go to auctions, but this was too good to miss. It was last summer, and Bonhams in Knightsbridge was holding one of its irregular design sales. Lot 114 was something I had lusted after for years: a complete bound set of Nova magazine, from 1965 to 1975, this collection including the dummy edition. Nova, not only the perfect manifestation of the Swinging Sixties, but probably the most influential women's magazine of them all, a kaleidoscopic amalgam of provocative fashion, hard-edged journalism and gender politics. The estimated sale price was £500-£800, so I thought I was in with a serious chance.

As far as I could tell - I was sitting in the front row - there was only one other person bidding for lot 114, so I figured they could drop out at any time. But they didn't, and as this faceless, silent hand behind me agreed £2,400 I shook my head and bowed out. As I wiped the sweat from my brow, my wife leant over and whispered, "It's Jarvis Cocker." "Him?!" I whispered back. "What the hell does he want those for? I hope he's going to steal the ideas and use them as well as I was!" In a way he already had. The cover of Pulp's 1995 LP, Different Class, was based on an old Nova layout, while the band's designers continue to plunder the magazine's typography. Cocker is very Nova himself: quintessentially arch, decidedly irreverent and studiedly cool. And someone who wears his social conscience on his sleeve.

Afterwards, we found ourselves in the same coffee bar. While I queued for some conciliatory cappuccinos, my wife went up to Cocker and asked him how high he would have gone, though on this occasion Cocker's legendary wit deserted him and he just shrugged and stared at the floor. So much for my first brush with Britain's most iconoclastic popstar.

Nine months later a brightly dressed Lowry stick man looms into the basement that houses Bunjies Coffee House and Folk Cellar, a bunker just off Charing Cross Road that probably hasn't changed since it opened over 40 years ago. Jarvis Cocker first discovered the place when he was studying at Central Saint Martins College of Art round the corner. Today he is wearing a black and white gingham overcoat, an ill-fitting black suit, a brown jersey and a pair of brownish pointy boots. He looks as though he buys his clothes in a place called the Dandy Fashion Charity Shop, and his middle-aged student ensemble - Cocker is 35 this year - is amplified by the carrier bag full of books he holds with both hands.

He seems distant, but quite personable. He does however, look incredibly miserable. Both in person and on record, Cocker has the requisite dour sensibility of a northern post punk bard, while Pulp's songs are like Mike Leigh plays set to music - little kitsch 'n' sink dramas about urban deprivation and strange sex. Cocker's lyrics, which are group's mainstay, are perfect examples of lo-fi realism, full of dirty fingernails and soiled undergarments, damp council flats and indiscriminate muggings.

His songs concern misfits, inadequacy (he once went on stage in a wheelchair), drugs and, most pertinently, class. He also makes a virtue out of celebrating the commonplace, much as Morrissey used to do when people took notice of him. Cocker is a man who likes fish and chips ("not fries"), PG Tips, Marmite (with the pre-1983 metal lids), red postboxes and Routemaster buses, smokestack skylines, the World Service (though not the new soap) and right wing politicians he can despise (he admits Tony Blair confuses him). You get the feeling that he'd prefer things to stay the same so he can remain in opposition. Like other miserabilists before him, Cocker is paradoxically vain. Speak to people who know him and they'll tell you that his biggest crime - his only crime, to be fair - is being too self-obsessed. It's hardly surprising that a pop star should be self conscious, particularly one who has wanted to be famous from an early age, but some are better at it than others. "He knows exactly how his shirt's behaving when you photograph him," says someone who has shot him several times over the past few years. "He composes his whole body in front of the camera as though he were a mannequin. It's like there's this ordinary man transforming himself into this weird-looking nerdy guy, but a weird-looking nerdy guy who knows exactly how he should be photographed, and from which side."

He is such a traditional English eccentric that by rights he ought to be gay, but he is anything but. While he looks more like an elongated, first year biochemistry student than a pop star, he has become something of a heterosexual rock god. When I interviewed him for The Sunday Times Magazine five years ago, he was just on the cusp of fame, and found this notion ridiculous. "If I do become a sex symbol I'll be overcoming my natural disabilities - I'm lanky, with bad eyesight. In reality I look more like an ugly girl."

He is such a traditional English eccentric that by rights he ought to be gay, but he is anything but. While he looks more like an elongated, first year biochemistry student than a pop star, he has become something of a heterosexual rock god. When I interviewed him for The Sunday Times Magazine five years ago, he was just on the cusp of fame, and found this notion ridiculous. "If I do become a sex symbol I'll be overcoming my natural disabilities - I'm lanky, with bad eyesight. In reality I look more like an ugly girl."

Today - perhaps slightly disingenuously - he says he still hasn't come to terms with it. "I think I've passed my sell-by date on that score. You might be sexy but you can't have sex with people. Because it ends up in the papers. You've probably got more opportunities than you've ever had at any other period in your life, but you can't really take advantage of them. Plus I think there's something deeply unsound about shagging someone who thinks you're great. Why spoil their beautiful dream by actually doing it to them? There's friend of mine who used to say that he wanted to become famous and then shag people really badly, like make it last 30 seconds, to puncture their illusions. He never became famous but I believe he did the second part quite a lot."

So, does he have a moral code? "Well, I'm not an angel, but your life loses its shape if you don't impose some discipline on it. Maybe I just keep saying it to try and keep myself out of trouble." One of the ways Cocker keeps himself out of trouble these days is by staying in his hotel room when the band are on tour. Pulp's recent single, which is also the title of their new LP, This Is Hardcore, was inspired by just that: hardcore pornography. "There's always an adult channel in the hotels where we stay, and each night I'd usually end up watching them. It's safer to stay in and watch a porno video than to go out on the town, and it made me think about the people involved in those films, and about the people watching." The song is also about coming a bit too close to the object of your desires. Perhaps the most pertinent lyrics on the new record are these: "I am not Jesus though I have the same initials, I stay at home and do the dishes."

Due to the global success of The Full Monty, Sheffield is currently enjoying the type of tourism usually reserved for Canterbury or Stratford-upon-Avon, and the city so filled with air conditioned coaches full of Japanese tourists looking for Shiregreen Working Men's Club, Bacon Lane bridge and the other local hot spots seen in the film. It is the city that Jarvis Cocker knows well. He was born there, and went to school in a downtrodden Sheffield suburb called Intake. By the time he had reached his teens, most of the city's industry had gone, and it was a bleak and depressing landscape for any adolescent to grow up in, let alone one as introverted as Cocker. His father left home when Jarvis was only seven. An acquaintance of the singer Joe Cocker, his father would often pretend to be his brother, a pose he kept up when he moved to Australia. Jarvis' mother was so hard up after he left that she took a job emptying fruit machines.

Forced to wear glasses after he contracted meningitis aged five, Jarvis' demeanour wasn't helped by the fact that his mother sent him to school wearing lederhosen, a present from some German relatives that she thought might look cute. He was not exactly an outgoing child. When he was 14 he was kidnapped by two middle-aged men in an Escort van, reluctantly agreeing to a lift after his mother had told him to be more sociable. The men then tried to sexually assault him, though Cocker says he outwitted them with sarcasm. There was a strong duality to his teenage years, with half of him lusting after an imagined Martini lifestyle ("I took far too much notice of magazines and TV"), and the other half firmly rooted in the housing estates of Intake. He had ambition, but wasn't sure what to do with it, and after narrowly failing to get into Oxford to read English, he went on the dole. For six years.

"I was always on the fringes of things at school, but when I left it became even worse. You can't help but feel marginalised when you're unemployed. We were a demographic group that absolutely no advertising was aimed at - basically we were the doley scumbags. And then after a while people become adrift, and without a structure you can quite easily end up sitting in your kitchen smoking all day which obviously isn't a good way to spend your life." On a whim, he formed Pulp with a bunch of friends in 1980, but during the next six years they experienced such a spectacular lack of success that not once did he come off the dole.

Such was his disillusionment with the group that he interrupted their rickety climb to stardom by enrolling at Central Saint Martin's in 1988 to study film-making. This obviously necessitated a move to London, which helped the nascent rock god become acclimatised to a world that up until then he had only fantasised about. He was both excited and repelled by what he found, as never before had he been exposed to so many people from so many different backgrounds. Saint Martin's was also where he met the "posh" girl from Greece for whom dirty East End bedsits and "common" working-class guttersnipes such as Jarvis seemed perversely erotic. It was she who would inspire the class-war anthem, Common People, what would later turn Pulp from an interesting bunch of second-raters into world-beating pop iconoclasts.

Back home I was very anti-London, very anti the fact that everything was based down here," says Cocker. "I'm glad I was brought up in Sheffield because although there wasn't anything going on, if there's no culture then you have to invent it. When I moved to London I was quite resentful. But I got over that. I didn't want to end up like one of these people with a chip on their shoulder who'll only go to pubs if they serve northern ale. The thing I had to get used to is that in Sheffield everything happens in the centre of town, it's like a village. When we came to London we used to do the same thing, we'd come into the centre of town on a Saturday night and stand in Piccadilly Circus and think, what the f*** are we supposed to do now?"

While at college, Cocker kept his band going, albeit on a part-time basis. Then, in 1993, having left Saint Martins, the world suddenly seemed to catch up with him and things started going right. All of a sudden Pulp were fashionable. Their single Babies (the narrative of which concerns a boy hiding in a wardrobe to watch his girlfriend's sister having sex) was picked up by a major record label, Island, and became a hit with the leather-jacketed inkslingers from the weekly music press. This was followed in 1994 by genuinely popular singles such as Lipgloss and Do You Remember The First Time (loosely based on Cocker's own loss of viginity, at the age of 19) and a hit album, His 'n' Hers. Critical mass was soon achieved with the monumentally successful singles Common People, Sorted For E's & Wizz and Disco 2000 a year later, along with their critically applauded breakthrough album, Different Class.

Suddenly Jarvis Cocker was a household name. And then no sooner had Cocker become famous that he did something so out of character that his world was changed forever. On February 19, 1996, he invaded the stage at the Brit Awards when Michael Jackson was halfway through one of his messianic hymns. Overnight, Cocker became a tabloid star, splashed all over The Mirror, The Sun and the News of the World, the lanky northerner who dared to attack the King of Pop. The attention still rankles. "It was like suddenly turning into Mickey Mouse," says Cocker. Rather ridiculously, this display cast him as some kind of rock 'n' roll animal. "Lots of people still expect me to be a Noel Edmonds type who's always doing a Gotcha, planting whoopee cushions under people's seats. It was only an expression of moral indignation, and I hate the fact that I'm still known for it.

"In Sheffield I had a lot of time to build up a picture of what fame might be like. But when you become famous you begin to wonder what defect in your personality made you want to be famous in the first place. "It was a very strange experience for us, having been so out of step with what was going on for years and years, to suddenly realise that we were producing something that was right for the time. Everything about the group happened in the wrong way, because by the age of 31 most people would have knocked it on the head. I suppose I'm a test case."

These days west London is his home. He lives with Sarah, a girlfriend of sorts, and Joel, a painter, in a spacious mansion flat in Maida Vale - "Media Vale", as Cocker calls it. For the musicians, artists, art dealers and fringe acquaintances of Cocker's new fame friendly world, his flat has become as familiar as the Groucho Club, the Atlantic Bar & Grill or Sadie Coles's trendy HQ gallery in Heddon Street. An elegant tip, with piles of uneaten food in the kitchen, dirty cocktail glasses in the bathroom and rows and rows of Cocker's oddball LPs pushed up against the living-room walls, it has all the trappings of student accommodation. It is also very 1970s and is full of tan leather sofas, smoked glass tables and chrome fronted mirrors. "The estate agent said, don't worry about the décor, it can be changed," says Cocker. "I went to look at it and it was perfect, it was somebody's 1970 bachelor pad and looked like the kind of place where you could make a porn movie. In a way it was good because I didn't have to take it seriously as a place to live."

Irony is a big thing in Cocker's world, something he used with ease when working his way through the mid-1990s, digital version of Swinging London. "It would be great to walk into a club like John Travolta dies in Saturday Night Fever and have everyone give you a high five and yelp hello, but the reality is having some p***ed-up bloke going, 'How's your mate Michael Jackson, eh?'" he says. "Having said that, I've been lucky. I've not had too many people wanting to kick my face in. At first I shied away from public places because I was embarrassed for my mates. I became a bit of a social liability." So for a while he did the Groucho and Blacks, the Soho House and the Union and Green Street, and most of the other private members' clubs in Soho where a paranoid pop star is always welcome, and where it's easier to indulge in the kind of behaviour that can get you thrown out of places where real people go. He was courteous, too, to the Imogens, Camillas and Jaspers he bumped into along the way, the very people he privately professed to despise.

"At first it was a bit like standing in front of a shop window, wondering how these people with their glittery lives actually behave," says Cocker. "I got invited to lots of dos, and after feeling quite marginalised for most of my adult life, to be allowed into that world, I had to go and look at it. It was natural human curiosity. It was like gate-crashing a party, but after you've gate-crashed it so many times you become part of the furniture." He stopped going out, he says, when he read that he'd attended the 10th anniversary party of Starlight Express. It was the London art mob that really fascinated Cocker, though - a bunch of belligerent bohemians who were creating a genuine social milieu. He began hanging out with Damien Hurst, Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas, and became the subject of several paintings by the portrait artist Elizabeth Peyton. The strongest relationship he forged was with the American artist John Currin, a latter-day Goya who has become something of a celebrity since his first British show last year. Cocker even asked Currin to collaborate on the sleeve and video of Pulp's recent single Help The Aged (a kind of When I'm 64 rewritten by Will Self).

"There is a shared aesthetic between John's paintings and the characters in Jarvis's songs," says Currin's dealer, Sadie Coles. "Essentially they are both dealing with human frailty and faded glamour. Cocker seems genuinely excited by the possibilities and the power of visual art, but although he's undoubtedly a great chronicler of our times, and there is often a genuine poetic quality to his writing, he's got quite a sad demeanour."

Cocker seems unduly secretive about his involvement in this world. He almost seems embarrassed by the notion of it, as though he might be getting above himself. "I know a few people in the art world, but I hated most of the poseurs at art school," he says immediately turning the conversation towards the past. "It's a cliché, isn't it, getting famous and then meeting other famous people? They put up the ramparts to keep you out, but if by some fluke you manage to breach the ramparts you're immediately into pro-celebrity golf land." You could say that Cocker cares more about not embarrassing himself than he does about anything else.

Cocker seems unduly secretive about his involvement in this world. He almost seems embarrassed by the notion of it, as though he might be getting above himself. "I know a few people in the art world, but I hated most of the poseurs at art school," he says immediately turning the conversation towards the past. "It's a cliché, isn't it, getting famous and then meeting other famous people? They put up the ramparts to keep you out, but if by some fluke you manage to breach the ramparts you're immediately into pro-celebrity golf land." You could say that Cocker cares more about not embarrassing himself than he does about anything else.

This involvement in the art world might yet bring him some satisfaction, as he is about to start filming three one-hour programmes for Channel 4 on "outsider art". Essentially a documentary about art made out of rubbish, the series began in southwest France, where a postman has built a palace in his back garden from stones picked up on his post round, and it ends in Los Angeles, at the salvage construction Watts Towers.

The series will take him away from London, and away from the goldfish-bowl life he has come to know these past five years. While he obviously enjoys much about his stardom, it doesn't seem to have made him particularly happy, and he certainly doesn't seem that fulfilled. He still enjoys making records, still enjoys performing, although you get the feeling that he knows that being a pop star isn't a dignified profession for a man in his mid-30s, even if he does still talk like a 18-year-old punk. Maybe he really wants to be David Bowie but feels vaguely embarrassed about the fact. Whatever, he certainly worries about his place in the grand scheme of things. It's this perpetual anxiety that made him - BBC fan or not - turn down a cameo on the recent Perfect Day record. He also refused to allow the Teletubbies to record a children's version of Common People, said no to a Mercury One 2 One commercial, and politely declined £5,000 to appear on Noel's House Party. Only £5,000? "Well, my credit's down at the moment. In a few months I'll be getting as much as Mr. Blobby."

What about ambitions, have they changed?

"I really hope I'm not performing in 10 years' time, but then 10 years ago I couldn't imagine myself still going to nightclubs, and I do. You tend to move the goalposts as you get older. I realised the other day that I've been in this group now for half my life, which is a very long time, perhaps too long. And there are certain things I should probably do. I wish I could be more pragmatic sometimes, but for some reason it doesn't seem to sit very easily with me. Maybe I'm just immature."

When I spell-checked his quotes after transcribing the interview, I was surprised to see the number of times Cocker had used the word "cliché", as though it were the devil's own mantra. The thought of softening at the edges obviously causes him great anguish. He is worried, too, that he is beginning to tolerate many of the things he used to despise. Having lived with failure for 15 years, having been the victim of cultural biorhythms, he is finding it hard to throw off his convictions. Maybe he should buy a Ferrari, or a yacht - something big and expensive, something to take his mind off being Jarvis. Perhaps he should stop being so hard on himself. After all, having waited over 10 years for success, couldn't he just enjoy himself a little bit more? I'm sure it would do him some good. He might even decide to give me back my Novas.

He is such a traditional English eccentric that by rights he ought to be gay, but he is anything but. While he looks more like an elongated, first year biochemistry student than a pop star, he has become something of a heterosexual rock god. When I interviewed him for The Sunday Times Magazine five years ago, he was just on the cusp of fame, and found this notion ridiculous. "If I do become a sex symbol I'll be overcoming my natural disabilities - I'm lanky, with bad eyesight. In reality I look more like an ugly girl."

He is such a traditional English eccentric that by rights he ought to be gay, but he is anything but. While he looks more like an elongated, first year biochemistry student than a pop star, he has become something of a heterosexual rock god. When I interviewed him for The Sunday Times Magazine five years ago, he was just on the cusp of fame, and found this notion ridiculous. "If I do become a sex symbol I'll be overcoming my natural disabilities - I'm lanky, with bad eyesight. In reality I look more like an ugly girl." Wimpey Bard: Jarvis Cocker Interview

Wimpey Bard: Jarvis Cocker Interview Cocker seems unduly secretive about his involvement in this world. He almost seems embarrassed by the notion of it, as though he might be getting above himself. "I know a few people in the art world, but I hated most of the poseurs at art school," he says immediately turning the conversation towards the past. "It's a cliché, isn't it, getting famous and then meeting other famous people? They put up the ramparts to keep you out, but if by some fluke you manage to breach the ramparts you're immediately into pro-celebrity golf land." You could say that Cocker cares more about not embarrassing himself than he does about anything else.

Cocker seems unduly secretive about his involvement in this world. He almost seems embarrassed by the notion of it, as though he might be getting above himself. "I know a few people in the art world, but I hated most of the poseurs at art school," he says immediately turning the conversation towards the past. "It's a cliché, isn't it, getting famous and then meeting other famous people? They put up the ramparts to keep you out, but if by some fluke you manage to breach the ramparts you're immediately into pro-celebrity golf land." You could say that Cocker cares more about not embarrassing himself than he does about anything else.