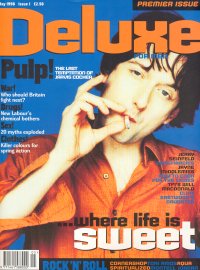

Words: Vivi McCarthy, Photographer: Simon Fowler

Taken from Deluxe Issue 1, July 1998

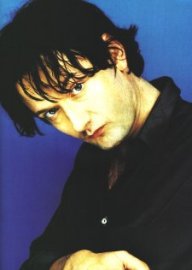

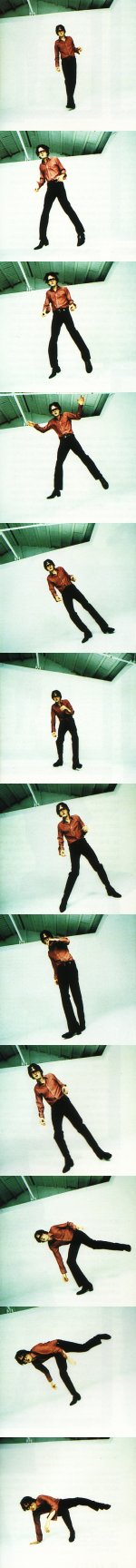

The Rake's Progress: Meet the new Jarvis Cocker. He's darker, he's dirtier, and now he getting messages from God. What next?

People change, but they want their favourite stars to stay the same. Throughout Pulp's Britpoptastic rise to fame, when everyone in Britain considered themselves part of the Common People, the band seemed to be the living incarnation of the way pop groups used to be on the telly You expected them to hang around together all the time and live in a communal comedy house like The Monkees or The Banana Splits - albeit one with 'erotic' prints on the wall. It would only have been right.

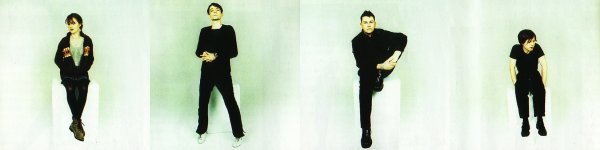

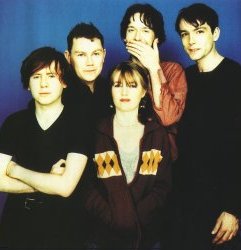

This rainy Friday afternoon, they arrive in a trickle, one by one, popping in from increasingly separate lives to reconvene in London and remind themselves that they are, after all, Pulp. It's taken them 90 minutes to assemble for the Deluxe photoshoot, and Pulp greet one another with simple "A'right?"s. Nick Banks (chunky drummer, co-owns a pub in Sheffield called The Washington) got the train from Sheffield, where he spent some time today clearing dog dirt from his garden. Candida Doyle (otherworldly keyboards woman, likes toys) came from her boyfriend's place in London. Mark Webber (Pulp's second guitarist and Troublesome Kid, runs a cinema club night at the London ICA where he shows art movies that border on pornography) arrived early and 'sparky'.

Jarvis Cocker has been in Stockholm, entertaining the press. Steve Mackey (spidery guitarist, now Pulp's chief arranger and technologist) arrives last and makes straight for the soft drinks in the fridge. He relates how he and Jarvis DJ-ed at a party for the Elite Models agency in Milan the previous week. "It was about the best DJ-ing Pulp have ever done, to be honest," he says. "We played 'Axel F' and Vanilla Ice. You stick them on over here and people go, 'Oh, it's so uncool, it must be great!' Which we never like. But for the Italians it never stopped being cool in the first place."

Jarvis Cocker has been in Stockholm, entertaining the press. Steve Mackey (spidery guitarist, now Pulp's chief arranger and technologist) arrives last and makes straight for the soft drinks in the fridge. He relates how he and Jarvis DJ-ed at a party for the Elite Models agency in Milan the previous week. "It was about the best DJ-ing Pulp have ever done, to be honest," he says. "We played 'Axel F' and Vanilla Ice. You stick them on over here and people go, 'Oh, it's so uncool, it must be great!' Which we never like. But for the Italians it never stopped being cool in the first place."

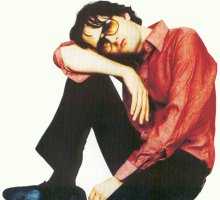

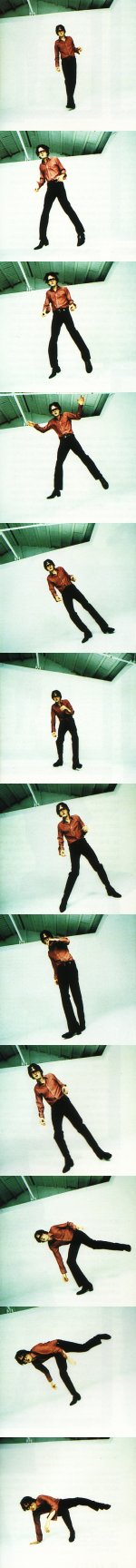

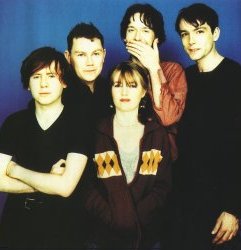

Pulp banter and mutter and mess with their clothes. Mark hands out fliers for his club to anyone who'll take one. Nick mentions that he and his wife now have a second kid on the way ("So that's twice he's done it now," someone calls out). There is an atmosphere of mild industry, because, in the parlance of the business, Pulp are about to start 'The Campaign' for their new album This Is Hardcore. It is their first since Different Class transformed them from Oxfam-togged weirdos into the authentic custodians of the British perspective, and it is a make-or-break record (but then, every record is a make-or-break record nowadays). To this end, Pulp's press officer has given them a carton of potential press shots, two or three of which need their approval. These are the pictures that will be sent out to every publication from the Stoke Evening Sentinel to The Face, so they're supposed to say something: we're hip, we look different from last time, we're back on the block and we've moved on. That kind of thing. This is a picture that has to be worth a thousand words.

Jarvis calls an impromptu band-meeting on the studio couch. Pulp rifle through the pictures, pulling them apart and telling one another how ancient they look. After much deliberation and inch-close inspection, they opt for a shot of all five on a couch. That's settled, then. "Oh, I dunno," mumbles someone. "We look like the M People." And straight to the bin it goes.

In this little micro-decision we have the two dilemmas of Pulp. Firstly, there's the age thing. Geeks have to grow up. In pop terms, Pulp were old when they made it. You know the story: 13 years spent on tiny labels won them a devoted cult following, but essentially for a long time the sound of Pulp was the sound of pissing in the wind. Then all of a sudden it wasn't and, in perhaps pop's most heartening moment of the 1990s, people started buying their records. Pulp were a bit wrinkly but their years were doubly pertinent because of what they sang about. Pulp had looked round and they'd seen us. They had seen us wondering whether to give up E or find a real job. Nothing had escaped them - not the fretting, the vomiting or drug-taking - and they summed up our existences in a way that gave some empathetic relief. Pulp were the band for people who should know better. Here was Jarvis, the wimp who spun on his heel and used his head to become cooler than the big boys who had rejected him.

Downtrodden outcasts, shy kids, strange kids, kids with big noses... all of them had a reason to hail geek's new king. Even hard-faced townies had to hand it to hirn. But who wants to be a geek forever? Who wants to do a Morrissey, be a gnarled Peter Pan wannabe still churning out songs of rejection? Who wants to be the oldest, saddest swinger in town? Where do you go post-bedsit? Next up there's the pop problem. Their new fame took them to new places; to the teen magazines, to the tabloids, to Hello! Like Blur and Supergrass they found themselves being pushed into a cute 'n' cuddly mould, rock sensibilities squeezed out in favour of pin-up posters and the need for a witty answer to questions like 'what colour are your pants?' Twelve-year-olds have limited attention spans and no loyalties. As M People have found out. Credibility; enigma, holding something back, not doing interviews, that's what keeps the punters keen. Ask Radiohead. If rock stars have maturity to fall back on, and there's no longevity in pop, where does that leave the pop group that wants to grow up with its dignity intact? Can Jarvis still be a spokesman for the underdog when he doesn't inhabit the same set of kennels anymore?

Downtrodden outcasts, shy kids, strange kids, kids with big noses... all of them had a reason to hail geek's new king. Even hard-faced townies had to hand it to hirn. But who wants to be a geek forever? Who wants to do a Morrissey, be a gnarled Peter Pan wannabe still churning out songs of rejection? Who wants to be the oldest, saddest swinger in town? Where do you go post-bedsit? Next up there's the pop problem. Their new fame took them to new places; to the teen magazines, to the tabloids, to Hello! Like Blur and Supergrass they found themselves being pushed into a cute 'n' cuddly mould, rock sensibilities squeezed out in favour of pin-up posters and the need for a witty answer to questions like 'what colour are your pants?' Twelve-year-olds have limited attention spans and no loyalties. As M People have found out. Credibility; enigma, holding something back, not doing interviews, that's what keeps the punters keen. Ask Radiohead. If rock stars have maturity to fall back on, and there's no longevity in pop, where does that leave the pop group that wants to grow up with its dignity intact? Can Jarvis still be a spokesman for the underdog when he doesn't inhabit the same set of kennels anymore?

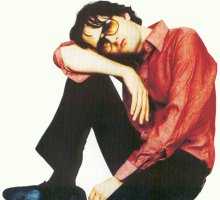

Jarvis is now 34 and rich but he still shares a house with flatmates. In some respects he lives like a student. "Maybe that's what I am doing," he says as the last of the pictures is completed and the lights are packed up. I hope not. We all don't sit around watching Men Behaving Badly. I just don't like living on my own, and I'm away a lot so if I was just living in a couple it wouldn't be much fun for the other person. Anyway, the combination of people is quite good. It works out well 'cause I never do the dishes. And I can cook a bit." Some would say that living like that, and dressing how you do, and being a pop star, are all just ways of avoiding growing up. "Well," says Jarvis archly, "Maybe it's time to invent an alternative form of adulthood."

Jarvis is now 34 and rich but he still shares a house with flatmates. In some respects he lives like a student. "Maybe that's what I am doing," he says as the last of the pictures is completed and the lights are packed up. I hope not. We all don't sit around watching Men Behaving Badly. I just don't like living on my own, and I'm away a lot so if I was just living in a couple it wouldn't be much fun for the other person. Anyway, the combination of people is quite good. It works out well 'cause I never do the dishes. And I can cook a bit." Some would say that living like that, and dressing how you do, and being a pop star, are all just ways of avoiding growing up. "Well," says Jarvis archly, "Maybe it's time to invent an alternative form of adulthood."

The other side of the weekend, Jarvis Cocker has jet lag. That's because he's in New York. The Campaign needs him here (though the Americans were ten years late with punk, they have developed an interest in colourful 'Disco 2000' Old Pulp just two years after the event). Last night, in the early evening, Jarvis fell asleep in his room at the Gramercy Park Hotel, and dreamed that his head was full of wasps. He's been dreaming a lot about wasps recently, swimming pools full of them. He doesn't know why, except that it worries him.

Jarvis has spent the last three days 'doing' American press and he's tired of explaining This Is Hardcore. You can see why: it is a proper, multistorey rock-opera of a record. It could simply be the tale of one man's trek through depression, from comic agoraphobia in 'The Fear' (Kenneth Williams does Joy Division) through joyless sex in '...Hardcore' ("What do you do for an encore?") to 'Party Hard', which explores the notion of your social life as a competitive sport, complete with injuries and of course, doping. It would be music to top yourself to were it not for the euphoric final track 'The Day After The Revolution', which recasts Pulp's pop explosion as a mere troublesome dream, dispels the gloom and ends with a wonderfully cheering statement of closure: "Sheffield is over... Irony is over... The Breakdown is over..." It's really Jarvis's honourable farewell to pop as Pulp used to play it. You could not guess what they are going to do after this. According to Mark Webber, it might well be Pulp's last record.

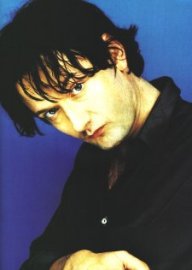

But Jarvis still has The Campaign to think of so we have retreated to somewhere peaceful quiet, St Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. It seems blasphemous to bring Jarvis The Pelvis but he wanders around the cathedral, the amber glow of a thousand candles reflected on his tinted James Garner spectacles, with detached but academic interest - although he 'wasn't brought up that way'. "It doesn't particularly excite me, 'cause I was in the Duerno in Milan last week," he says. "You go up onto the roof on that one. It's really good. But I like churches 'cause there quiet places to go. They're building a non-religious cathedral in Germany at the moment - a big white building, just a silent place to go and think. That's a good idea, that." He parks his crumpled, beige-clad self in a pew.

But Jarvis still has The Campaign to think of so we have retreated to somewhere peaceful quiet, St Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. It seems blasphemous to bring Jarvis The Pelvis but he wanders around the cathedral, the amber glow of a thousand candles reflected on his tinted James Garner spectacles, with detached but academic interest - although he 'wasn't brought up that way'. "It doesn't particularly excite me, 'cause I was in the Duerno in Milan last week," he says. "You go up onto the roof on that one. It's really good. But I like churches 'cause there quiet places to go. They're building a non-religious cathedral in Germany at the moment - a big white building, just a silent place to go and think. That's a good idea, that." He parks his crumpled, beige-clad self in a pew.

"I remember when I first moved down to London. I had to get the express coach down overnight, and I had about three hours to kill before the place opened where I was going to get my flat. So I went into St Paul's and sat in there. It was great 'cause there was no one around." He looks up at the altar. "And there really is a place for somewhere like this in New York." Jarvis has a strange relationship with New York. He doesn't seem to like it, but it's one of the few places he can go without being That Guy From Pulp. At Christmas 1996 he came to Manhattan for his own kind of retreat. Jarvis hates being on his own, because he spent too much time doing that as a kid, but then it was not a particularly good time of his life. Pulp were at a lull.

They had finished touring the previous summer a two-month holiday, and decided to plough straight into writing a new album. It didn't quite happen. In October they got together and tried again. And again, it didn't quite happen. Pulp had but one song, 'Help The Aged', which they'd written on tour, and the scraps of a couple of others. They wasted time and each other's patience. None of them can agree on why. Nick said they were suffering from nervous expectancy, "Like when you're decorating, and you see what you've got do and think, 'Can I be arsed to do it?"' Candida confessed, "The last thing I wanted to do was get together with Pulp again." Steve thought they needed another rest, "a chance to find a new kind of direction".

They had finished touring the previous summer a two-month holiday, and decided to plough straight into writing a new album. It didn't quite happen. In October they got together and tried again. And again, it didn't quite happen. Pulp had but one song, 'Help The Aged', which they'd written on tour, and the scraps of a couple of others. They wasted time and each other's patience. None of them can agree on why. Nick said they were suffering from nervous expectancy, "Like when you're decorating, and you see what you've got do and think, 'Can I be arsed to do it?"' Candida confessed, "The last thing I wanted to do was get together with Pulp again." Steve thought they needed another rest, "a chance to find a new kind of direction".

All of them knew there was a question mark over Jarvis' lyrics, which were previously the great unifier, bringing all of Pulp's baroque pop ideas together when they were added right at the end, to otherwise completed songs. Jarvis had written all the lyrics to Different Class in two days - an extraordinary feat considering its breadth of vision and murderous sense of humour, but then not all that extraordinary, really. After all, he'd had 14 years to work them out. As Nick said, "Last time Jarvis's lyrics were all ready to come out, weren't they? This time was... different. Bound to be."

So Jarvis went to New York, checking in at the chi-chi Paramount Hotel off Times Square for three weeks of musing. It wasn't exactly a monastic retreat - he does actually know a few people there, and somehow he was 'hounded' by a woman called Imogen from New Labour who kept phoning him in the early hours to ask if the then-opposition could still rely on his support. (I told her to fuck off. I don't know how they tracked me down. Nobody was supposed to know I was there"). But it enabled him, somehow, to sort his head out. "It doesn't make sense if you think about it logically," he says. I was in this cramped little room and it was very.. I don't know, I just needed to get away. I'm good at putting decisions off anyway, but when you're on tour you put even more things off because you've got the more pressing business of getting yourself on stage everyday. Decisions about your personal life get shoved off into the distance. Then you finish touring and instead of, like, two or three things to sort out, you've got a big pile of things. "Plus," he adds. "You're fucked. Mentally"

Then Jarvis starts shaking his head and changing the subject in that working-class-embarrassed way he has. He tells me he doesn't believe in analysing himself - "people go up their own arse" when they do - and all that stuff about wanting to get in touch with the inner you, the child within... it's all rubbish. Children don't analyse things, he says. They just accept stuff at face value, so how are you supposed to get in touch with the child within by analysing your life to death? Doesn't make sense. It seems strange talk from someone who's written some of the most psychologically telling pop lyrics of recent years, but he's having none of it. "I don't need to do that stuff. I get bored with me own company," he explains. "But I did have to think about myself a bit when it came to starting to do the record. Whether it was worth doing another one, for a start. Usually when people get to their early thirties they're kind of settled, so it was a bit weird to have your life turned upside down at that time. All over again."

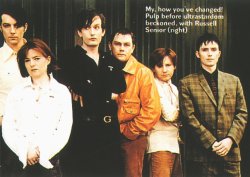

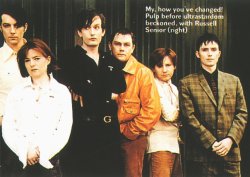

When Jarvis came home, Russell Senior, who had been in Pulp since 1983 announced that he was leaving. Pulp are enormously cagey about the reasons, but the general pattern which emerges is that Russell, a father, disliked every part of being in Pulp which involved getting to and coming off stage (the recording, the mixing, the interviews, the flying) and so decided to make a clean break. Nick began to miss the little pile of roll-ups that used to surround Russell when he played. Steve missed the arguments: "He argued, which was positive, because you really had to argue your case, think about what you were doing." For a while Steve says, Pulp became too 'nice' and agreeable for the group to function. They ground out This Is Hardcore at a painful pace. I think all of us wanted to leave at some point," Candida said. But now it's done and they seem as puzzled by it as they are proud. As if they didn't know they had something so harsh and enigmatic and ultimately idealistic in them.

Well, this is all very nice. We have repaired to a cafe in Manhattan's citadel of the entertainment industry, the Rockerfeller Plaza. Jarvis glances out onto kids skating on the outside rink while smoothing out four pages of fax paper on the table. They are ...Hardcore reviews straight from the British press. "Pulp have made the best album of their career," he reads, then shoves the paper back into his pocket and stares into space. "Great," he smiles. "We can retire now." Jarvis isn't entirely convinced that this is good news. He doesn't believe much of what the papers say anymore. "I'm not casting doubts on your critical faculties," he tells me, "But lately the critics have got it pretty wrong, haven't they, on most of the kind of big albums that have come out. I mean, in the Blur-and-Oasis, Great Escape versus What's The Story thing, they got it completely wrong. Then everyone said Oasis's last album was brilliant when it came out, and then retracted it a month later. So we won't really know how our album's going to do until it gets out, will we?"

As Jarvis peers at his water glass - his eyesight is famously dreadful - some kid bursts an enormous balloon at the next table. Jarvis shouts "Fuck!" and everyone looks at him. It takes him some seconds to collect his thoughts. We've been talking about a certain morbidness in Pulp's album, suggesting it has an undercurrent of death-temptation. It certainly has the same ultrablack humour as the 'Help The Aged' video, which ended with Pulp disappearing off to heaven with all the other raddled oldsters on a set of infinitely long Stannah stairlifts. How about it, then? Is this Pulp's last will and testament? "I don't really relish the idea of dying, but nobody does, do they?" Jarvis begins, slowly. "Maybe I might have been thinking about it a bit more because... because we had achieved something at last. And you might think, oh well, I've done it now, I might as well top meself. I've done as much as I'm gonna do. I mean, it's a way to think, isn't it?

"But I didn't intend to write specifically about me. For instance, 'The Fear' is about a lot of people who have suffered from the hedonism of the past four or five years. Some of them ended up in mental health day centres. I know that 'cause two of my flatmates work in them. The record's not entirely about me." Not even 'A Little Soul'? Here's a song about a meeting between a father and his long-abandoned son. Tellingly, Jarvis sings not as the boy but as the dad: "I wish I could say I stood up for you and fought for what was right, but I never did / I just wore my trenchcoat and went out every single night." Everyone knows Cocker's father skipped home and emigrated to Australia when Jarvis was just seven, his most memorable recollection being that his father had "a scrotum like a bag of marbles".

"Well, I'll tell you what did that. One of my flatmate's dads had been ill. It happened really suddenly and he got summoned up to Sheffield, basically 'cause he thought his dad were gonna die. And, er, he didn't in the end so that was quite good..." A sip. "...But it kind of got me thinking about my dad, and what it would be like to go and see him. It always gets romanticised that particular story, doesn't it? It's a standard plot device in East Enders. Long lost parents turn up and they start rowing and stuff. I thought maybe I would be more likely to just hate him. Or whatever." A lengthy pause. Then: "I dunno. It's funny." The weirdest thing anyone has said about This Is Hardcore so far, he says, is that the record - this comic, pornographic wallow through the worst the human race has to offer - is really about God. Maybe it's that redemptive bit at the end.

"Though, actually," Jarvis adds, "a very strange thing happened when we were recording 'The Day After The Revolution' which ought to have, you know, converted me. We knew we wanted it to be quite busy at the end, with a few different voices talking on it, and I got this radio to put a bit of radio noise on it. I couldn't really hear it when we recorded it, so I just stuck it behind the song. When we listened back to it in the studio it was like some religious broadcast. I honestly hadn't heard it. It's about the creation of the world. Just as the song fades out it says something like, 'And God called the expanse sky'. And that's it. It was a weird coincidence. And because the song's about maybe a sense of rebirth and this speech is about the creation of the universe, it seemed a bit..." His voice trails off and all he can do is wave his hands spookily. The Lord works in mysterious ways.

A woman, posh, old and English in a large fluffy bear-hat, approaches our table and asks Jarvis if she should know who he is. Ever the gentleman, he says he has no idea. Maybe her daughter might know, she says. Maybe so, Jarvis smiles back, and off she goes, muttering something about keeping her eyes peeled. It seems like Jarvis's idea of a perfect conversation. "A lot of people talk too much," he says. "That's when I am crushingly bored. When people just gab too much, it's such a waste. I'd rather do things than talk. I'd rather just ride me bike somewhere or y'know, not just witter on about bollocks. All people ever want to talk about is themselves, isn't it?"

That guy from Pulp finishes his water and prepares to leave, to deal with the Americans, to get back into The Campaign. He pulls on his jacket - another nightmare in beige - and looks back at the kids on the skating rink, whirling around in circles on artificial ice in the shadow of giant buildings. Jarvis is happy because, for the moment at least, those kids have absolutely no idea of who he is.

Jarvis Cocker has been in Stockholm, entertaining the press. Steve Mackey (spidery guitarist, now Pulp's chief arranger and technologist) arrives last and makes straight for the soft drinks in the fridge. He relates how he and Jarvis DJ-ed at a party for the Elite Models agency in Milan the previous week. "It was about the best DJ-ing Pulp have ever done, to be honest," he says. "We played 'Axel F' and Vanilla Ice. You stick them on over here and people go, 'Oh, it's so uncool, it must be great!' Which we never like. But for the Italians it never stopped being cool in the first place."

Jarvis Cocker has been in Stockholm, entertaining the press. Steve Mackey (spidery guitarist, now Pulp's chief arranger and technologist) arrives last and makes straight for the soft drinks in the fridge. He relates how he and Jarvis DJ-ed at a party for the Elite Models agency in Milan the previous week. "It was about the best DJ-ing Pulp have ever done, to be honest," he says. "We played 'Axel F' and Vanilla Ice. You stick them on over here and people go, 'Oh, it's so uncool, it must be great!' Which we never like. But for the Italians it never stopped being cool in the first place." Confessions Of A Pop Star

Confessions Of A Pop Star Downtrodden outcasts, shy kids, strange kids, kids with big noses... all of them had a reason to hail geek's new king. Even hard-faced townies had to hand it to hirn. But who wants to be a geek forever? Who wants to do a Morrissey, be a gnarled Peter Pan wannabe still churning out songs of rejection? Who wants to be the oldest, saddest swinger in town? Where do you go post-bedsit? Next up there's the pop problem. Their new fame took them to new places; to the teen magazines, to the tabloids, to Hello! Like Blur and Supergrass they found themselves being pushed into a cute 'n' cuddly mould, rock sensibilities squeezed out in favour of pin-up posters and the need for a witty answer to questions like 'what colour are your pants?' Twelve-year-olds have limited attention spans and no loyalties. As M People have found out. Credibility; enigma, holding something back, not doing interviews, that's what keeps the punters keen. Ask Radiohead. If rock stars have maturity to fall back on, and there's no longevity in pop, where does that leave the pop group that wants to grow up with its dignity intact? Can Jarvis still be a spokesman for the underdog when he doesn't inhabit the same set of kennels anymore?

Downtrodden outcasts, shy kids, strange kids, kids with big noses... all of them had a reason to hail geek's new king. Even hard-faced townies had to hand it to hirn. But who wants to be a geek forever? Who wants to do a Morrissey, be a gnarled Peter Pan wannabe still churning out songs of rejection? Who wants to be the oldest, saddest swinger in town? Where do you go post-bedsit? Next up there's the pop problem. Their new fame took them to new places; to the teen magazines, to the tabloids, to Hello! Like Blur and Supergrass they found themselves being pushed into a cute 'n' cuddly mould, rock sensibilities squeezed out in favour of pin-up posters and the need for a witty answer to questions like 'what colour are your pants?' Twelve-year-olds have limited attention spans and no loyalties. As M People have found out. Credibility; enigma, holding something back, not doing interviews, that's what keeps the punters keen. Ask Radiohead. If rock stars have maturity to fall back on, and there's no longevity in pop, where does that leave the pop group that wants to grow up with its dignity intact? Can Jarvis still be a spokesman for the underdog when he doesn't inhabit the same set of kennels anymore? Jarvis is now 34 and rich but he still shares a house with flatmates. In some respects he lives like a student. "Maybe that's what I am doing," he says as the last of the pictures is completed and the lights are packed up. I hope not. We all don't sit around watching Men Behaving Badly. I just don't like living on my own, and I'm away a lot so if I was just living in a couple it wouldn't be much fun for the other person. Anyway, the combination of people is quite good. It works out well 'cause I never do the dishes. And I can cook a bit." Some would say that living like that, and dressing how you do, and being a pop star, are all just ways of avoiding growing up. "Well," says Jarvis archly, "Maybe it's time to invent an alternative form of adulthood."

Jarvis is now 34 and rich but he still shares a house with flatmates. In some respects he lives like a student. "Maybe that's what I am doing," he says as the last of the pictures is completed and the lights are packed up. I hope not. We all don't sit around watching Men Behaving Badly. I just don't like living on my own, and I'm away a lot so if I was just living in a couple it wouldn't be much fun for the other person. Anyway, the combination of people is quite good. It works out well 'cause I never do the dishes. And I can cook a bit." Some would say that living like that, and dressing how you do, and being a pop star, are all just ways of avoiding growing up. "Well," says Jarvis archly, "Maybe it's time to invent an alternative form of adulthood." But Jarvis still has The Campaign to think of so we have retreated to somewhere peaceful quiet, St Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. It seems blasphemous to bring Jarvis The Pelvis but he wanders around the cathedral, the amber glow of a thousand candles reflected on his tinted James Garner spectacles, with detached but academic interest - although he 'wasn't brought up that way'. "It doesn't particularly excite me, 'cause I was in the Duerno in Milan last week," he says. "You go up onto the roof on that one. It's really good. But I like churches 'cause there quiet places to go. They're building a non-religious cathedral in Germany at the moment - a big white building, just a silent place to go and think. That's a good idea, that." He parks his crumpled, beige-clad self in a pew.

But Jarvis still has The Campaign to think of so we have retreated to somewhere peaceful quiet, St Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. It seems blasphemous to bring Jarvis The Pelvis but he wanders around the cathedral, the amber glow of a thousand candles reflected on his tinted James Garner spectacles, with detached but academic interest - although he 'wasn't brought up that way'. "It doesn't particularly excite me, 'cause I was in the Duerno in Milan last week," he says. "You go up onto the roof on that one. It's really good. But I like churches 'cause there quiet places to go. They're building a non-religious cathedral in Germany at the moment - a big white building, just a silent place to go and think. That's a good idea, that." He parks his crumpled, beige-clad self in a pew. They had finished touring the previous summer a two-month holiday, and decided to plough straight into writing a new album. It didn't quite happen. In October they got together and tried again. And again, it didn't quite happen. Pulp had but one song, 'Help The Aged', which they'd written on tour, and the scraps of a couple of others. They wasted time and each other's patience. None of them can agree on why. Nick said they were suffering from nervous expectancy, "Like when you're decorating, and you see what you've got do and think, 'Can I be arsed to do it?"' Candida confessed, "The last thing I wanted to do was get together with Pulp again." Steve thought they needed another rest, "a chance to find a new kind of direction".

They had finished touring the previous summer a two-month holiday, and decided to plough straight into writing a new album. It didn't quite happen. In October they got together and tried again. And again, it didn't quite happen. Pulp had but one song, 'Help The Aged', which they'd written on tour, and the scraps of a couple of others. They wasted time and each other's patience. None of them can agree on why. Nick said they were suffering from nervous expectancy, "Like when you're decorating, and you see what you've got do and think, 'Can I be arsed to do it?"' Candida confessed, "The last thing I wanted to do was get together with Pulp again." Steve thought they needed another rest, "a chance to find a new kind of direction".