Pulp TV

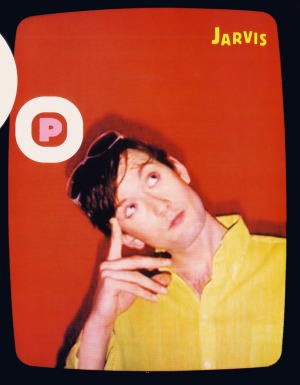

Pulp TVLadies and gentlemen: introducing Sheffield's own Jarvis Cocker, man of the common people, unlikely sex symbol, top pop personality and the best TV presenter we never had. Jarvis always wanted to be a pop star, even if it meant performing with a hoover or selling crabs.

Taking a shallow drag on his Silk Cut, he leans forward with a conspiratorial glint in is eye. Interviews seem to be the only occasions on which Jarvis cocker, Pop Star, smokes. They're not the only occasions on which he talks. We've been sitting in his manager Geoff Travis' tiny office at the Rough Trade building in Ladbroke Grove, west London, for nearly three hours. It's almost 11pm now, and for the last 15 minutes Travis has been ostentatiously pacing the adjacent room and gestating wildly that it really is time to go. Really. The thing is, Jarvis, who has his back to the door, can't see his manager and I'm saying nothing. He's just warming to his subject. The secret of his success.

"It's like this," he explains. "There's something freakish about you, so you either consign yourself to the margins of society or think of it as unique."

How do you mean, Jarvis?

"Well, I was amazed when I first saw a picture of Jean Paul Sartre. I mean, you think of him as this bohemian, Left Bank Parisienne cool guy who had this bizarre erotic relationship with Simone de Beauvoire for all those years. You do, don't you? Then I saw a photo of him and the first thing I thought was, 'Boss-eyed get!' You know? Very ugly man. One eye's looking over here and one eye's way over there. I just thought if he can get over that, which is generally a bit of a no-no as far as going out with girls is concerned, then there's a chance for me."

It's Friday and this has been a long, intensely exciting week for Jarvis and his group, Pulp. Five days ago, while they were hanging around waiting to mug a Radio 1 Roadshow, the news came through that their single 'Common People' had leapt straight into the charts at number two. Thereafter, events had spun out of control. They did Top of the Pops on Wednesday, a FACE cover shoot on Thursday, Richard and Judy this morning. This afternoon, they spent three-and-half hours signing records, posters knickers - anything - at HMV's Oxford Street megastore. According to the store's staff, it was the wildest and best-attended signing since Morrissey appeared 18 months ago.

Particularly sweet is the fact that almost no one had seen any of this coming. The record company hadn't even wanted to release "Common People" yet, so far ahead of the next album, which is scheduled for October. But Jarvis felt that, "for once", one of his songs was in tune with the zeitgeist. "Common People" concerns "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". It was initially inspired by a couple of rich-kid girlfriends of his, but Cocker took the view that a recent proliferation of Mike Leigh video box sets indicated that the song's sentiments might have wider resonance. To watch him shuffle foot- draggingly down the street in a lime green shirt, blue double-breasted suit and specs, surrounded by a swarm of girls half his height (six-foot-four), half his age (31), looking for all the world like a lost, colourblind, geography teacher on a field trip to London, is to suspect that he was right. If there has never been a more unlikely pop star, there have also been a few better ones.

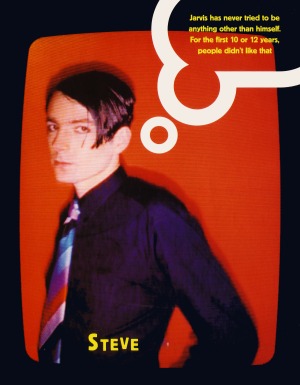

Only the most irredeemable sourpuss would so anything other than rejoice in Pulp's success. Jarvis Cocker has spent over half his life trying to arrange it, 17 years. He has said in the past that, if he'd known it was going to take this long, he wouldn't have bothered. Probably, he was not joking. For years, he will confess, he had it in for John Peel, because it was the session Pulp did in 1982 that persuaded the 18-year-old Cocker to stay in Sheffield and persevere with the group rather than take up a place at Liverpool University.

Pulp's - Jarvis' - popularity has little to do with the music, which, while capable of flirting with greatness ("Lipgloss", "Joyriders") and growing the more you experience it live, is nevertheless, at root, a nicely turned out but remarkable strain of leftfield pop. It is more to do with Jarvis himself, with the fact that, like all the best pop stars, he can mean pretty much whatever you want him to mean. It's true that some of the girls at the HMV signing, when asked what they saw in Jarvis, did begin with, "He's gorgeous", but they tended to do so with something less than total conviction. That's what they're supposed to say. It's their job. Dig a bit deeper, though, and you found that the man's image is almost uniquely malleable. He's smart, common, freaky, geeky, stylish, funny, profound, mysterious, sensible, a great lyricist... the only thing all the fans agreed on is that he's "different". They like him for that.

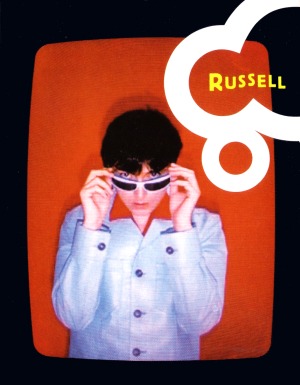

Latterly, Jarvis also seems to have become the essence of sexiness for many older women. The rest of the group find this mystifying and endlessly entertaining. At the photoshoot, while Jarvis was busy trying on clothes, there was a chance to talk to them. Russell, Pulp's waggish guitarist of 12 years, first met Jarvis when the singer was working in the market. "I used to go watch him selling fish," he grins, "He'd charm all these old ladies into buying more crabs than they needed and things. They loved him: he'd be, like, 'Would you like an extra claw, Mrs Hayworth?' - so the sexual innuendo was there at an early age, really. That was what brought us together. He was a very good fishmonger."

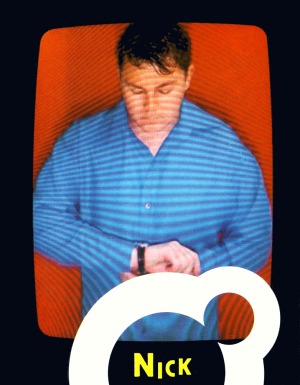

Their first collaboration, curiously enough, was on a stage play. "It was an attempt to be a Dada-ist play, where you'd do things like leave a Hoover on till people started getting pissed off. Jarvis was the main protagonist. They'd throw things at him. That was very pleasing to us at the time." What Russell neglected to mention, according to Jarvis, is that he wrote this play. As to sexiness, the guitarist was unashamedly amused. "You know," he says in his South Yorkshire drawl, which is noticeably broader than Jarvis', "it's only a few years ago that I ever heard a girl say anything about him other than, 'Who's that lanky get?'" Like Russell, Nick, Pulp's solid no-nonsense marvellously archetypal drummer, has lived with Jarvis. He is more specific in his mystification. "I find it quite strange, because when you see him pottering about the house or whatever, he was very clumsy. He falls over the pattern in the carpet, doesn't he? He took his glasses off - what about four or five years ago? - in a vain attempt to appeal to the opposite sex... and it seemed to work. Strange."

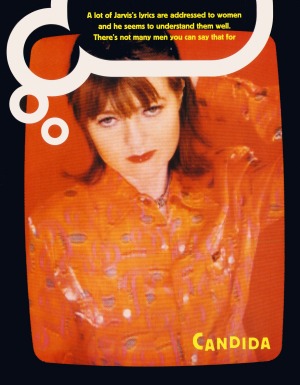

Interestingly, only keyboard player Candida has little trouble understanding the phenomenon. "But a lot of it's personality," she commented. "Character. A lot of his lyrics are addressed to women and he seems to understand them well. There's not many men you can say that for." She went on to sympathise with the predicament Jarvis now finds himself in, always being expected to be funny and entertaining, to have an opinion on everything. "Yeah, but that's what Jarvis is good at," Russell reassures her. "He couldn't do anything else. Me and Nick have both lived with him. Before we lived together, I'd always known him sociably and you always expected this Jarvis act would be dropped at some point during the day. But you can sit down to watch Neighbours and he'll be pacing about the room, striking poses and putting on stupid voices, speaking to the characters like they're guests in our house and we're all sat down having tea together. I'm going, 'Look, Jarvis, there's just me here, you're not on stage, just sit down, eat your tea and let me watch the goddam telly!' But there's no point in saying to him, 'You don't have to be Jarvis, you're not onstage', because he always is. I've never seen him being 'natural',"

The rise of Jarvis has produced many cherishable moments. There was the "I Hate Wet Wet Wet" sign on Top Of The Pops. There was Pop Quiz, where, drunk, he feigned boredom with Chris Tarrant and the horse the whole enterprise rode in on, then answered every single question in the quick-fire round, thus leading his team to triumph. His subsequent, one-off stewardship of Top Of The Pops, during which he routinely ridiculed those appearing on it, rendered the programme watchable for the first time in... possibly ever. Who among us hasn't dreamed of doing these things? Or at least appointing someone to do them for us? It was as if Jarvis had been reading out minds. You have a sense that, whenever he appears on the box, he is doing it for us.

Best of all, though, was his speech at the Mercury Awards dinner last year. Prior to the announcement of the winning LP, a member from each nominated group - Pulp were in the running for "His 'n' Hers" - was supposed to say a few words. Jarvis stalked up to the podium. "Music is my first love," he announced in sombre tones. Everyone laughed heartily at the opening line from John Miles' notoriously pompous late-Seventies tribute to, er, music. "And it will be my last," Jarvis added. The second line. More laughter. "Music of the future." Silence. "And music of the past." What? Was he going to? Yes, he did, the whole song.

Before the photo session, I'd met Jarvis once before, when he was still languishing in relative obscurity. I'd found him funny and eccentric, but - and I was sure this wasn't my imagination - diffident, suspicious. So is his today. He will later explain that he tends to get on more readily with women than men. He has an actor's eyes, unblinking, steady and expressionless. His presence doesn't derive from his height, it comes from the fact that you never know what he's thinking until he says it. To watch him gradually drop his guard will be interesting.

Jarvis has just returned from the offie across the road bearing some cans of Red Stripe for me, plus a ten-pack of Silk Cut and - this raises a smile - a half bottle of Martel brandy for himself. One of the first things you notice about Jarvis when you get up close is that, contrary to what the music press would have you believe, he is quite handsome. He may need feeding up a bit, but he has bone structure. How does he feel about people - mainly men, one suspects - seeming to find it so odd that a skinny, speccy guy like him should be considered sexy? That even the rest of Pulp consider this a cause of great mirth?

"Oh, but I think a skinny bloke looks much better than a muscley bloke," he retorts, settling into his chair. "If you look at THE FACE, the male models are usually terrible. It's shocking! They've always got this wide, thick-set, pit bull look to them, with cropped hair and stuff. And they always have shit clothes on as well. To me, that's not a good way for a man to look. The thing is, you have certain hand of cards that you're born with and you either play with what you've got or rail against it. I suppose I've railed against mine to a certain extent. I was supposed to be a bit of a swot at school. I was lanky and I had braces on me teeth, was pretty much a mess, was pretty much a mess. The group has always been a vehicle for me to alter myself. I don't look like Richard Gere or Johnny Depp. I know that, but there are certain things about yourself that you think, 'Maybe if I take this thing and accentuate it as far as I can and explore and not be embarrassed, then maybe you can make yourself into something a bit different.'"

You're saying that you've invented yourself?

"I'm a self made man, me. Yeah."

Did you always want to be famous, Jarvis?

"Yeah, I was desperate to be famous."

Did you care what for?

"I always wanted to be in a pop group," he says.

Jarvis always uses the word "group" to describe Pulp, never the more portentous "band". He loves pop, the immediacy of it, the fact that you can write a song and get it out there quick, that people will then take it from you and infuse it with their own passions, turn it into something else entirely.

"To me, it's interesting that you can somehow lock into other people's lives. I was always aware of not fitting in totally, so the ides that me, being a bit of a misfit, can do something that then gets bought by ordinary people... that pleased me because it means that you've somehow been able to weedle your way into mainstream society."

Jarvis was first introduced to pop via his mother's Beatles records. He describes her as a "bit of a beatnik": he's seen pictures of her jeans and sandals and stripey T-shirts. She bummed around Europe, started at art college, then became pregnant with Jarvis and her bohemian years came to an end. Jarvis suspects that she was always disappointed with her two children for staying in Sheffield. "She probably felt like she'd been cut off in her prime, so when we got to our teenage years, she was thinking, 'Don't do the same as me, go and enjoy yourself while you can.'"

Cocker's need to wear glasses - the lenses of which look thicker at close quarters than they do from a distance, when your attention is diverted by the outsize frames - stems from a severe bout of meningitis he contracted when he was five. His memory of this is of everybody buying him all these great presents, "because they thought I was going to die", then of his having to leave them behind when he didn't, as they were contaminated and had to be burnt. Then, when he was seven, and without warning, his dad skipped home and emigrated to Australia, where he told everyone he was Joe Cocker's brother (not true) and got a job as a rock DJ.

Jarvis has three distinct memories of his father. The first is that he played in a band. The second is that, when he burped, he always said "Archbishop of Canterbury" in a burpy voice. The third is of his testicles. Jarvis used to study them while the old man was giving him and his little sister a bath. "My dad's scrotum was like a bag of marbles," he muses, wrapping his long legs around those of his chair and leaning back to gaze at the ceiling. "It looked like there was about ten in there." When the boy Cocker reached teenage and only had two, he adds, he thought there was something badly wrong with him. This story probably contains the seeds of everything you need to know about him.

According to those who know Jarvis well, his dad's actions have had a profound effect on his life and music. Jarvis doesn't disagree. "I think a lot of the reason I found it difficult when I started going out with girls was because I was brought up around so many of them. Through a biological accident there are lots more females than males in my family and I just thought of them as friends and considered myself to be the same as them. But when you start going out with people, you start to realise that the battle of the sexes does exist."

Do you think men and women are fundamentally different? The brow furrows deeply. He adjusts his glasses. He drags on his fag and takes a swig of brandy. "This is something that I've wondered about quite a lot recently. I never used to think they were. Now I think, due to the biological facts, that there is a fundamental difference... I think there is a fundamental attitude to sex. I do think that women get more pleasure from sex than men. If it's done properly. Why? I don't know why that is. But I know that the feeling a man gets at the point of orgasm is not that different to if he masturbates or something. You don't feel particularly transported beyond yourself, I don't think."

You've never felt transported?

"Sometimes, yeah. That's what you aim for, I guess..."

Jarvis laughs suddenly and rocks back in his chair. "I feel myself on dodgy ground here." One suspects that his sensitivity to this is related to the attraction he holds for many women. "I feel myself on dodgy ground here." One suspects that his sensitivity to this is related to the attraction he holds for many women. "The thing about sex is that it doesn't fit in with the society we live in. Everything else is quite regulated, but sex is still an area that's kind of grey, which I suppose is why I write about it a lot... no one can take you to court and say, 'This person shagged me and left the next morning and never called me for a fortnight.'"

Accordingly, we find nestled in Jarvis' portfolio such family favourites as "Babies", which features a boy hiding in his older sister's wardrobe, thereby ensuring that he is on hand (as it were) when she brings her boyfriends home after school. (Jarvis' sister, we should note, is younger than him.) Then there's "Underwear", which is on the b-side of "Common People" and will appear on the new album. This deals with that eternal dilemma, the one facing you at 4am when you find that you've gone home with someone and now realise that it "wasn't such a good idea", as Jarvis puts it. Are you going to go through with it? There's this hollow feeling at the point of orgasm, which is one of the most intensely unpleasant feelings a man can have...

"Yeah, it is a horrible feeling," Jarvis interjects. "It makes you feel something less than human, like you can get carried away with this need...I don't know... See, sometimes it seems like a great thing to do, to shag someone you don't know well or care about. It's a mental thing. Your body's saying, 'Go on, do it. Offload that!'" He laughs. "Just get it done. And in a way, I think there is something enticing about impersonal sex."

"The only similar thing is having a kebab. Everybody knows that kebabs are a bad idea. They do, really. You can't excuse them on any grounds of nutrition or otherwise, but somehow, when you're really pissed, really fucking hammered, you get into that perverse frame of mind where you think, 'Right, I'm hammered. I'm a mess. How can I take it further?' And the answer is: 'I'll have a kebab.' Somehow it rounds the experience off and you get some kind of perverse satisfaction from the knowledge that you were low, and yet you thought of a way of taking it lower. And there is something you can learn from that - not necessarily something that you'll want etched on your gravestone, but it's good to acknowledge that sometimes you get those unwise impulses. Somehow, from taking it that far, you get something out of it."

It's ironic that the decisive influence on Cocker's songwriting and on Pulp's success was his move to London in 1988, to study film at St Martin's School of Art. It looked to him like his days as a stagestruck pop nymphet were over, but the upheaval had two unexpected side-effects. First, it slipped him a dose of that frustrated, nerve-jangling energy enforced celibacy invariably brings with it. For three years, no one wanted to sleep with the Sexiest Man In Pop. He'd been a virgin till he was 19, yes, but that was six years previously. Second, it made him look at his past and at Sheffield with fresh eyes. "In my naivety, I thought the whole world was like Sheffield. When I found myself in a different environment, I thought, 'I'd better write all this stuff down before I forget it, 'cause I'm not living like that any more.' People in London don't go round saying, 'Ah, that's ace, that' and 'I fingered her at t'busstop - awright?' Things that seemed too obvious to write about before weren't any more."

Cocker is often described as his generation's Alan Bennett (though he himself claims the detail-rich New Journalism of Tom Wolfe is more of an inspiration). And yet, one still suspects that a major part of Pulp's current success derives from Jarvis' swaggersome TV performances. It's already being said that he is the best presenter we've never had. Would he consider a step in that direction? "I wouldn't leave the band at the moment." It would be the perfect career move, though. Utterly surreal.

"Well, I'm alright on telly because I don't have to do it as a job. It always used to piss me off how, with youth programmes, they always have to pick some presenter who's like the worst hyperactive teenager who was in your class at school. If I was a pop TV presenter, it wouldn't work: people wouldn't come on, because they'd think I was going to slag them off." This is, of course, precisely the show we've always wanted. "Maybe in later life I could do it. That was the other thing that irritated me. Whenever me favourite groups got on telly when I was a teenager, they always seemed to be right boring. They'd say things like, 'Yeah, we recorded the latest album in Montserrat, man, yeah and we've been working with a lot of really good people, we've got a really good vibe down...' These aren't interesting things to hear. So whenever I've been on telly, I've wanted to go against something. I don't see why it should just be the seasoned professionals, the boring, cheesy bastards who can be articulate. It's not a skill. For whatever reason, I am able to talk, but I'm not proud of it. I don't consider it a skill."

There's a silence. Jarvis takes another sip of the brandy which is by now seriously depleted. It's been a long day. He leans back again, purses his lips and pouts, and I realise that he's considering something. Later, listening back to the tapes, I also realise that his speech has become less distinct than it was and that his Sheffield accent has grown marginally more pronounced. Jarvis decides to say what he wants to say. "I went for a job, actually." A job? Where? "When The Tube first started. That's what made it such a joke to me when they repeated it. I went for a job as a presenter. I was 19 at the time. I didn't get it, obviously. As soon as they said they were going to repeat The Tube, I said, 'Don't get excited, because all we're going to get is Paul Young.' That is their most heinous crime, inventing Paul Young. He was a fucking club singer and they had him on there, probably because another band dropped out. then they kept having him on there, even though he did a cover version of 'Love Will Tear us Apart', which fucking tore me apart, I'll tell you. That song tore me apart, hearing him sing that song."

Jarvis, pop fan's pop fan that he is, was clearly terribly upset by this. "That was when music went wrong. That was when it lost it, during that decade. I hope that, after that trauma, pop music's actually getting its act together and realising why it exists again now."

Why does it exist?

"It's about a cheap thrill, I think. When pop music first arrived, it was considered the most ephemeral, stupid thing that could be, something that would never last. Now you've got all these Capital Gold type stations playing records from 30 years ago, records which were considered to be something that would last for six weeks, then forgotten. It's all staid, which is to miss the great thing about pop music, which is that it's cheap and it's throwaway, but somehow - and nobody really knows exactly how - a song can crystallise a certain moment and a certain feeling. You don't get that from big, important Eighties type attitudes like Live Aid and 'Feed The World'. It just happens and it's a random thing and that's what I like about it."

This implies that you don't expect longevity for yourself.

"No. For me, that's the point of Pulp. Things that aren't thought to have any artistic worth at all. For me, that's the stuff that more often than not ends up having some impact, stuff that's just pumped out for the sake of it, not stuff that thinks it's God's gift to mankind. Whenever music starts taking itself too seriously and getting a sense of its own importance, it fucks up. When it's just dealing with the surface, or making a noise to make things more bearable, that's when it's doing something good. That's when it can be profound, I think."

This implies an attitude to life. Is this a devil-may-care, live-for-the-moment, hope-I-die-before-I-get-old type thing?

"Oh, I'd love to live for the moment. I've tried all my life, but I just can't manage it." Jarvis is not laughing. "No, I really would like to. I think that's the best way to live, and I aspire to living like that. I think it's very difficult." Why is it so difficult? "Well, if you've got a brain, you can't help but think about things. You meet someone, you talk to them and suddenly you've planned you whole life together and what you'll do when you buy your first house together. And how you're going to bring the kids up. You just can't help it, you get home and get to bed and suddenly these thoughts start invading your head and you can't stop them. It just happens. Maybe I'm immature."

Do you think you're immature?

"Yeah, definitely, I'm very imma, yeah." Imma? "Yeah, imma. That's what we call it in Sheffield. 'You're imma, yow!' Yeah, definitely, I'm very imma. I was even told it when I was at school, that was the sad thing. The French teacher used to say to me, 'You can't be bloody Peter Pan all your life.'"

Immaturity is often confused with romanticism, I say. Jarvis leans back and takes a final wire-limbed slug of Martell. His French teacher was probably wrong.