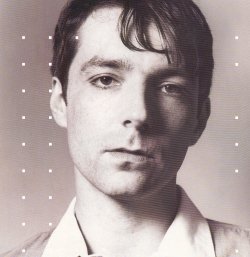

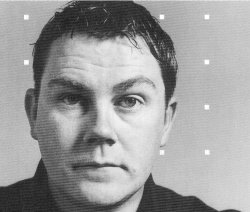

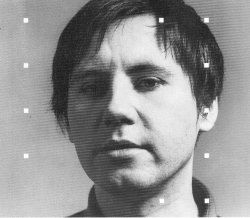

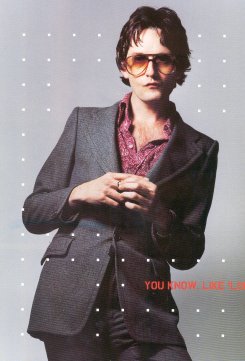

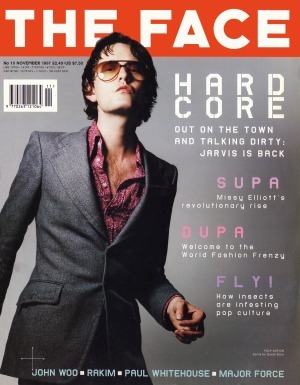

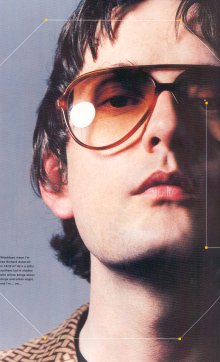

Words: Alan Smithee, Photographer: David Sims

Taken from Face Magazine No 10 Vol 3, October 1997

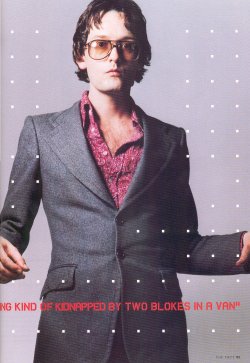

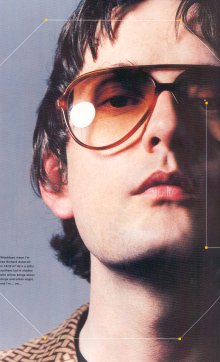

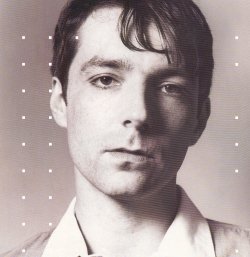

This is the tale of a northern soul. A lad - gangly, gawky, speccy - who was a freak for 32 years and a genius for two. A pop star who, for a minute there, was the most famous man in the country. Then Jarvis Cocker started listening to Radio 2 and writing about pensioners. Then Pulp came back.

Here, in the no-place that is studioland - the world of sub-audible and exact tape alignment and flanged microglide - the small conservatory-like structure was like a concession. Like an afterthought or add-on; a few cubic metres of wood-and-glass-enclosed, human-textured rumpus space. Crowded into it, refugees from the processed air and electronic circuitry, fully immersed in the day, keeping real rather than rockbiz time, was most of Pulp (Candida was still on her way).

Something about them (I saw them a few seconds before they caught sight of me) suggested a domestic tableau, with something promisingly skewed or off-kilter, as if framed by Spielberg or adult-era Walt Disney: a group of UFO spotters killing the daylight hours until the start of the main event. Or a family group waiting for the car to get loaded so that the holiday they have all been dreading can begin.

Jarvis Cocker filled the doorway leading to a small mossy yard, the designated interviewing place. In the yard was a green patio table to which each band member would come in turn to talk ("divide and rule", as guitarist Mark Webber said). Beyond it, the opaque green windows of the bathrooms of half-a-dozen west London bedsits and flats. Visible behind most of the windows were shadowy rows of medicines and aspirins and lotions and powders and gels - micro-histories of toilet articles. The kind of histories that Jarvis, as the originator and far and away the leading practitioner of a new kind of dandiacal, up-from-the-gutter dirty realism ("No wonder you're looking thin, when all you live on is lipgloss and cigarettes... All those nights in, making such a mess of the bed"), is around to tell.

Like a Saul Bellow character - a Herzog, a Mr Sammler (these are not such crazy comparisons) - Jarvis is "a delicate recording instrument", "a prisoner of perception, a compulsory witness". It is what makes him one of the most distinctive writers working in Britain at the minute, and one of the best songwriters - in a tradition that is traceable through The Beatles and The Kinks to music hall and vaudeville - to come out of this country in some years. "He looked out, noticing. What a man he was for noticing!" as Bellow writes in one of his novels. "Continually attentive to his surroundings. As if he had been sent down to mind the outer world, on a mission of observation and notation."

In a relatively short time - only a bit more than two years - Jarvis has become one of those people we look to (John Lennon was one, Francis Bacon was another) to bring us back the news about ourselves. After 16 years of finding himself consistently out of step not just with the music business but with the wider world, he suddenly found, with "Common People" in 1995, that he had hit a nerve. "It was one of those rare moments," he says, "when you produce something at the time when people seemed ready for it to happen."

Then on February 19 1996 (tell him about it), Jarvis Cocker invaded the stage at the Brit Awards where Michael Jackson was doing his Messiah from Motown bit. Overnight he turned into one of those people who are known for being known, even among people who have no idea why what they are known for matters.

"I remember waking up the next morning and it was like that thing when you've done something embarrassing the night before," Jarvis says as he takes his turn at the patio table. "It was the same kind of feeling, except that it wasn't just my embarrassment, everybody else knew it had happened as well. It's like suddenly turning into Mickey Mouse. It didn't go away."

"I was on me chair clapping," remembers bass player Steve Mackey. "At the time I wasn't thinking, 'Oh fuck.' I felt more proud of him for being still Jarvis, that rag-arse who can do stupid things. It just reminded me of what he's always been like. That's why I felt quite proud that he was still willing to stick his arse out in front of people and not give a shit what they thought. Just, you know, that he wasn't playing the pop star game."

"I was on me chair clapping," remembers bass player Steve Mackey. "At the time I wasn't thinking, 'Oh fuck.' I felt more proud of him for being still Jarvis, that rag-arse who can do stupid things. It just reminded me of what he's always been like. That's why I felt quite proud that he was still willing to stick his arse out in front of people and not give a shit what they thought. Just, you know, that he wasn't playing the pop star game."

The problem with the Jackson fiasco was that it seemed to fix Cocker in an older rock 'n' roll tradition - one of hysteria in limousines and knife fights in the audience, of ego-bloat, pandemonium and drugs. This would be funny if it didn't continue to cast such a long shadow over his life. His natural area of operations is more domestic: "I am not Jesus though I have the same initiaIs/ I stay at home and do the dishes" as he sings on one of the songs from the new album.

"Jarvis captured the mood of the nation," Steve says. "But if you ask him about that incident, it's probably the thing in his life that he regrets more than anything. Because it just led to him being followed around by people with long lenses for six months and appearing in the tabloids."

Steve: "Last year I seemed to he in this band where Jarvis was always able to judge 'the mood of the nation', d'you know what I mean? Michael Jackson, Leah Betts, "E's and Wizz" ,.. Even though they were just events that happened, it becomes a kind of trusim he's always a step ahead of the people in England; that he's a style barometer. I don't think he ever tried to create that position. People did it around him. But I just thought, I hope we're not going to go though another record of him being a step ahead of the media, telling everyone how it is. That's not the Jarvis I know at all."

Jarvis: "I don't want to be Mr Topical. Some kind of bloody I-know-what's-right smart-arse wagging his finger at everybody. I don't want people to think that about me, that I'm some knob'ead trying to make these searing social insights into the state of Britain in the Nineties all the time. Because how often do you get a really big insight into things? It just happens sometimes, and you can't force it".

I've stopped being an observer and started reading the Observer." Jarvis once offered this as throw-away line but - the watcher becoming the watched, the snooper snooped - it has had important consequences for his work. "This Is Hardcore", the new Pulp album, which is due to be released next spring, has taken a year to make. The commitment to throwing everything away in the hope of coming up with something radical and new meant that, for a time, they were left with nothing and found it difficult to start at all. "We'd do a song and then it would just go in the can for two months," Mackey says, "and that's never happened before. I mean, a song's just a record of how the people involved were feeling at that time. And if the people involved don't have the desire to put that song away, that's the reason it goes off the desk and back in the can again. We all agreed that what we'd recorded was really good, but somehow we couldn't seem to finish it for a while."

In the 17 years that he has been fronting Pulp, one thing has never varied: Jarvis has always been the lyric supplier, and the lyrics have always come at the end. "The lyrics always seem to be the very, very last thing that ever get done, so you never know what the lyrics are going to be," drummer Nick Banks says. "The group's never meddled in the words. Never ever. There's never been any need. It's always been: 'Here are the words.' And we've always gone: 'Great! Top!' But it's become quite obvious that he's been finding it more difficult to come up with a real angle on life and what people are actually thinking and how life actually goes on."

For his part, Nick has gone back to live in Sheffield, where they all started ("big fish in a small pond, that kind of thing'), where life actually goes on, where he has half-shares in a pub. (Jarvis: "Drumsticks over the bar." really? "Not really.") "I've always liked to think of meself as having me feet on the ground,' the drummer says, just in case there's room for doubt.

For his part, Nick has gone back to live in Sheffield, where they all started ("big fish in a small pond, that kind of thing'), where life actually goes on, where he has half-shares in a pub. (Jarvis: "Drumsticks over the bar." really? "Not really.") "I've always liked to think of meself as having me feet on the ground,' the drummer says, just in case there's room for doubt.

"I'm very sceptical about all these art openings and poncing around Soho clubs, with Jonathan Ross over here, and whoever else over there. 'So tell me about your latest book.' 'No, tell me about your latest pilot show.' I can't be doing with it. It's not really an option, I don't think. I'd rather just be with real people in the end."

But the slummers, slappers and single mothers of "His 'n' Hers" and "Different Class", the divs, misfits, mistakes and thickos, are people that Jarvis now regards as belonging to his past. "With the last record," he muses, "we achieved what I suppose we'd all been trying to do for the last ten years. So the question after that becomes: 'Have you said what you wanted to say?' In which case there's no point keeping on saying it over and over again, because that only dilutes what you said in the first place.

"And in any case, I can't really do that stuff any more because, I mean, I don't want to be a designer northerner. You know: 'Look at these Versace clogs.' I've not lived there for nine years now, so I've got no right to write about it. I wrote those songs when I first came down to London because it was like I wanted to get it all set down on paper before I forgot what it was like. And I'm inhabiting a different world now, for better or for worse. And you have to write about what you know.

"An obvious problem of becoming well-known, though, is that it has become more difficult for me to socialise normally... When we played at V96 [Pulp's last public UK appearance during the long "Different Class" haul] I went out and had a walk in a gorilla suit. Nobody took any notice of me at all. So that was quite funny... But it did all do me head in for a bit." People close to him, meanwhile, suggest that, perhaps as a corollary of the adulation from the public and the media he was, getting, Jarvis was suffering from writer's block. That his abrupt change in lifestyle had left him unsure of where his future subject matter might come from. As Damon Albarn acknowledged in a story about Britpop's tabloidisation in FACE 91, when you make a career - forge an artform - from the poetry of crappy places and commonplace things and ordinary people, this can be a problem.

"An obvious problem of becoming well-known, though, is that it has become more difficult for me to socialise normally... When we played at V96 [Pulp's last public UK appearance during the long "Different Class" haul] I went out and had a walk in a gorilla suit. Nobody took any notice of me at all. So that was quite funny... But it did all do me head in for a bit." People close to him, meanwhile, suggest that, perhaps as a corollary of the adulation from the public and the media he was, getting, Jarvis was suffering from writer's block. That his abrupt change in lifestyle had left him unsure of where his future subject matter might come from. As Damon Albarn acknowledged in a story about Britpop's tabloidisation in FACE 91, when you make a career - forge an artform - from the poetry of crappy places and commonplace things and ordinary people, this can be a problem.

The dislocation kept coming: earlier this year, Russell Senior left Pulp. The guitarist was a Pulp veteran (only Jarvis tops Russell's 14-year membership of the group) and a kind of shadow to the singularly idiosyncratic Jarvis. It is this very "shadow" notion that is the problem. Could this have been the most extreme result of the apparent struggles within Pulp, a public release for the toes squashed and egos bruised as Jarvis - willingly or not - stepped to the fore? Or was Russell bored, and simply wanted to spend more time with his family? Whatever, relations remain amicable, with Russell turning up at Jarvis' birthday party last month.

"It was a big deal," Jarvis concedes. "It was just something that happened, and it was quite weird at first without him, and I do miss him sometimes. But I don't really want to talk about it, because I'm quite proud of the fact that we managed to do it in a fairly human and civilised way." A few months previously, Jarvis had been photographed by Terence Donovan for the cover of GQ's -Cool Britannia" issue. He now regards those pictures as a repository of all the disorientation and life-laggedness he was feeling. "He was really nice, but those pictures convinced me that I had to disappear for a long time. I've never been able to bring meself to look at them. I look like some kind of bloated... mess. I just look vacant. Like I've had something sucked out of me.

"The way I think of it is in terms of the placards you have in a hairdresser's window, with the pictures of the hairstyles that you can get inside. And they're in colour, but then they've been in the window for ages and all the colour drains out and you're left just with light blue - blue seems to be the last layer of the printing process and you're just left with these faded blue pictures. And it's like that, you know? It's like you're subjected to this glare of relentless scrutiny, and if you don't apply a bit of shade to yourself, then you'll just fade and eventually you won't have any personality left. So you have to keep something back for yourself. Which was never a problem before. I had loads left back for meself, because nobody was arsed about who I was. It wasn't an issue then. But it is an issue now. You have to remain a human being. I think that's quite important."

"The way I think of it is in terms of the placards you have in a hairdresser's window, with the pictures of the hairstyles that you can get inside. And they're in colour, but then they've been in the window for ages and all the colour drains out and you're left just with light blue - blue seems to be the last layer of the printing process and you're just left with these faded blue pictures. And it's like that, you know? It's like you're subjected to this glare of relentless scrutiny, and if you don't apply a bit of shade to yourself, then you'll just fade and eventually you won't have any personality left. So you have to keep something back for yourself. Which was never a problem before. I had loads left back for meself, because nobody was arsed about who I was. It wasn't an issue then. But it is an issue now. You have to remain a human being. I think that's quite important."

"The most noticeable result of all this upheaval and flight is a backing away, in the new songs, from the self- confessional, nakedly autobiographical style that brought him to fame. "I'd never really wanted to have a really 'private' life before. But when somebody starts delving into it and printing details about your goings-on, dragging you through the tabloids for shagging people you shouldn't have shagged, then that probably made me shy away a bit more from giving too much away. Because if you give everything away then you become a kind of non-person."

"This Is Hardcore" itself is one of the few full songs I hear in my day in Pulp's rumpus space. It is a carefully-constructed studio masterpiece that artfully subverts what, to the lazy ear, might sound like middle-of-the-road. A similar notion of subversion-from-within informs Pulp's faithful take on Rita Coolidge's "All Time High" for this month's James Bond "tribute" album "Shaken And Stirred", the stately lushness of their putative Bond theme "Tomorrow Never Lies", and their crooning country ballad "Laughing Boy". These latter two tracks appear on the B-side of Pulp's new single, "Help The Aged". Like "This Is Hardcore", "Help The Aged" starts with a tinkling piano passage that sounds like standard, white-bread Radio 2 fare. And Cocker confirms that, over the past year, Radio 2 has frequently been his channel of choice.

"Things like Desmond Carrington on Sunday afternoons. He does play a lot of rubbish, but he also plays stuff that's kind of been shunted off into a corner. A lot of it is just nostalgia stuff, but occasionally you get something that transcends that. it's always good to find something in a place where you wouldn't expect it.

"Help The Aged", first aired at V96 and the first Pulp single for 18 months, was the only song they wrote during the world tour that started the day after the Brit Awards. That tour would keep them away from home for the best part of eight months. In the course of it, Jarvis found himself increasingly brooding on thoughts of dying and death.

"But I think I probably have a natural bent toward morbidity anyway."

"Help The Aged" developed out of soundcheck noodlings and, at a first hearing, sounds uncharacteristically benign: an anthem for the new, compassionate, touchy-feely, post-Diana Britain. And then you get a big crunching guitar and the chorus: "When did you first realise? / It's time you took an older lover, baby / Teach you stuff, although he's looking rough / Funny how it all falls away". These, it seems, are long-running concerns of 34-year-old Jarvis Branson Cocker. "I think someone had to make a stand and say adulthood doesn't have to consist of going to the South Bank and watching a Latin American film festival," he said back in 1994. "I desperately have to believe adulthood can be interesting because I'm there."

Three years on, his personal and professional landscape may have changed beyond recognition, but the song remains the same: "In your mind you try to picture old people, and you think of the songs they play on Radio 2, and it's as if people are suddenly going to flip over and start listening to Vera Lynn records or something when they get to, like, their fifties. But obviously that's not going to happen, is it? You can see it on Radio 2 now, where they get all the stuff that's been rejected by Radio 1, such as Tina Turner and Eric Clapton. It's really going downhill.

Three years on, his personal and professional landscape may have changed beyond recognition, but the song remains the same: "In your mind you try to picture old people, and you think of the songs they play on Radio 2, and it's as if people are suddenly going to flip over and start listening to Vera Lynn records or something when they get to, like, their fifties. But obviously that's not going to happen, is it? You can see it on Radio 2 now, where they get all the stuff that's been rejected by Radio 1, such as Tina Turner and Eric Clapton. It's really going downhill.

"Finding some way of growing old gracefully seems to be quite difficult. You don't want to end up, like, fucking walking around the South Bank saying, 'Yeah, we went to this great salsa festival and I bought some lovely South American crafts...' The most exciting things are the things you do when you're young. So I don't know how you get round that. Perhaps by following the example of that couple in the papers who went out and started holding up post offices. It's a much better way to spend your dotage than mouldering away in some decrepit flat somewhere. "But it is difficult to see anything positive about getting older, although I'm determined to try, because otherwise, what's the point? And so 'Help The Aged' is an autobiographical song. That dread of dying. I need some help. The only way I can deal with things is to make them so that I can laugh at them in a way. Even though it scares me to death."

At the end of a long day's fat-chewing, I went with Jarvis and Steve to the Groucho Club in Soho. A few days later I met up again with Jarvis for dinner at the Chelsea Arts Club. Afterwards we went to the Met Bar at the Metropolitan Hotel in Mayfair where we stood next to a man who was carrying £12,000 in twenties in a carrier bag. It's the kind of itinerary that would give Nick Banks night fevers and that has got Jarvis written up as part of the shifting population of celebrity rent-a-faces and table-hoppers, shuffling from film premiere to private view to roped-off restaurant. The London Evening Standard took particular pleasure in running a spread of pictures of him squeezed off at a dozen such events a while ago, like he was some sex beast recently released into the community, and this was a public service.

"It wasn't my main ambition in life to get invited to premieres," he said, only medium-exasperated. "But when I started to get invited, it was quite exciting, because it was like the whole thing that happened three or four years ago, when suddenly groups that would have been considered indie groups or alternative groups started getting in the charts. The so-called Britpop explosion. I didn't like the idea of being marginalised and being like this lost bunch of disenfranchised people. And so when I got invited to things, I think just natural human curiosity means that you will turn up. But then once you've gone, 'Oh look, there's Wayne Sleep over there, ha ha,' once, it kind of wears off. Because then it made me feel like that kind of shitty 'We're all one big happy family in showbiz'. It's like people kind of shit on you and try to keep you down for as long as possible, and if you somehow manage to slip through the net, it's like 'C'mon darling, yes! We always knew you'd make it! Mwah, mwah!' I hate all that pally, let's-go-and-play-some-pro-celebrity-golf bollocks."

In its original formulation back in the day - 1995 - "Britpop" meant just four groups: Blur, Oasis, Suede, Pulp. Now Blur have -gone difficult" as Jarvis puts it, and Suede have plateaued, and Oasis� -Blur said they wanted what Oasis wanted," Steve Mackey says. -But I think the truth of the matter is that Blur didn't really want it. Because you've got to go out and just fight for it, and the Gallaghers were prepared to go out and do that, work their arses off non-stop. Most people realise it's not worth working that hard for. But the Gallaghers really wanted that thing, and they'd do anything to get it. You're never going to win against them on that, are you? They've learnt that money means power and they use it. I find it all a bit scary."

In its original formulation back in the day - 1995 - "Britpop" meant just four groups: Blur, Oasis, Suede, Pulp. Now Blur have -gone difficult" as Jarvis puts it, and Suede have plateaued, and Oasis� -Blur said they wanted what Oasis wanted," Steve Mackey says. -But I think the truth of the matter is that Blur didn't really want it. Because you've got to go out and just fight for it, and the Gallaghers were prepared to go out and do that, work their arses off non-stop. Most people realise it's not worth working that hard for. But the Gallaghers really wanted that thing, and they'd do anything to get it. You're never going to win against them on that, are you? They've learnt that money means power and they use it. I find it all a bit scary."

On the Saturday between our meetings, Jarvis went to see Oasis play Earl's Court, where they were supported by The Verve. "I hate it when groups slag each other off," he had said. -It's pointless really. Because unless you're really shit, you always think that you're better than everybody else. So you're never going to have a good word to say about another group, probably. It's the way it goes."

He liked The Verve though, and was prepared to admit it. -They were really good," he said, not daunted so much as put on his mettle, and just pleased to be going up against an outfit with a reachier punch. It's about competition, and competition as the spur to greater achievement and contentment. And 1997 is the year that competition came through in droves. Oasis went rusty, Blur went AWOL, Suede went on, Radiohead went cosmic, The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers went global, U2 went down, Supergrass and Portishead went back to go forwards. Only The Verve, of all the big artists putting out big records this big year, have managed to connect in a way that Jarvis connected a year or so ago. Will Pulp still connect? Maybe the question facing them - Jarvis, really - is of how far you can take a connection built on ordinariness, when that very ordinariness you had has made you and your life so extraordinary. Or something.

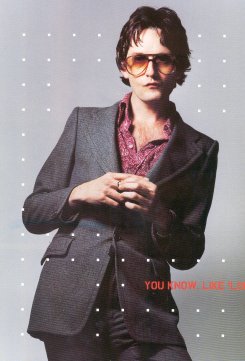

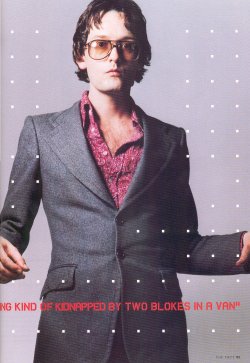

A week before I met Jarvis for dinner, I'd seen him at the opening of the Sensation exhibition as the Royal Academy in Piccadilly. He was wearing open toed sandals, a Gucci style tote bag, and a binocular case: there was going to be a full eclipse of the moon that evening, and he had brought his field-glasses to watch it happen. The overall effect was a kind of chic bag-person look - a high-street ranter; a picker and hoarder living in a house of junk. This kind of sartorial unpredictability has become Jarvis Cocker's stock-in-trade. Today, interview day, his hands were blue from the undesigner jeans and new jeans jacket he was wearing. Eccentricity, he says he learned at an early age, was always going to be his best line of defence.

"I remember when I was really young seeing George Melly on this telly programme," Jarvis is saying now as he leans on the bar at the Met. -He was saying that quoting surrealist poetry at a gang of blokes who were about to cave his head in had saved him. And being this knobhead with specs on driving this stupid little Hillman Imp, I found it very useful. Because it unsettles people. Once people get the smell of fear and know you're frightened of them, in a way it turns then on, and they'll really go for it. If you react in a way they don't expect you to, it unsettles the situation."

"I remember when I was really young seeing George Melly on this telly programme," Jarvis is saying now as he leans on the bar at the Met. -He was saying that quoting surrealist poetry at a gang of blokes who were about to cave his head in had saved him. And being this knobhead with specs on driving this stupid little Hillman Imp, I found it very useful. Because it unsettles people. Once people get the smell of fear and know you're frightened of them, in a way it turns then on, and they'll really go for it. If you react in a way they don't expect you to, it unsettles the situation."

"I've had a number of situations like that. I had a situation where I was kind of kidnapped. I was about 14 or 15 and I had been going through this stage where me mother had been telling me that I had to be more... sociable. I was walking down the road where I lived and this Escort van pulled up and this bloke got out and said: 'We're going to go an' pick these gates up down the road, can you give us a hand to carry them? And because me mother had told me all this stuff like, 'be friendly, make friends', I got in the back of this van. And there was another kid about my age in the back of it. Then about a mile away from our house, they told the other kid to get out and guide them into this driveway. But as soon as he was out, the driver bombed off."

"So now I'm stuck in the back of an Escort van with these two blokes, and there was this kind of silence. I just didn't know what was going to go on. Anyway they drove out till they got to this golf course, stopped, and then the fat one turned round and he goes: 'How big's your knob?' And I think if I'd really've been abjectly cowering in the back of this van at this point, something really horrible would have happened. But I just said: 'I've never measured it.' Then he goes: 'Do you wank yourself off?' And I said: 'Well, you've got to haven't you, otherwise your balls'd explode.' Something stupid..."

"And then there was the most pathetic part of the whole situation - he starts spraying me with little bursts of anti-freeze. Anyway, they finally let me out and drove off and I made it home. But the moral of the story is that, if I would have let them know I was scared of them, I would have put them in a position of power. And they would have exploited it, I'm sure about that.

"I was on me chair clapping," remembers bass player Steve Mackey. "At the time I wasn't thinking, 'Oh fuck.' I felt more proud of him for being still Jarvis, that rag-arse who can do stupid things. It just reminded me of what he's always been like. That's why I felt quite proud that he was still willing to stick his arse out in front of people and not give a shit what they thought. Just, you know, that he wasn't playing the pop star game."

"I was on me chair clapping," remembers bass player Steve Mackey. "At the time I wasn't thinking, 'Oh fuck.' I felt more proud of him for being still Jarvis, that rag-arse who can do stupid things. It just reminded me of what he's always been like. That's why I felt quite proud that he was still willing to stick his arse out in front of people and not give a shit what they thought. Just, you know, that he wasn't playing the pop star game."  The Face Interview

The Face Interview For his part, Nick has gone back to live in Sheffield, where they all started ("big fish in a small pond, that kind of thing'), where life actually goes on, where he has half-shares in a pub. (Jarvis: "Drumsticks over the bar." really? "Not really.") "I've always liked to think of meself as having me feet on the ground,' the drummer says, just in case there's room for doubt.

For his part, Nick has gone back to live in Sheffield, where they all started ("big fish in a small pond, that kind of thing'), where life actually goes on, where he has half-shares in a pub. (Jarvis: "Drumsticks over the bar." really? "Not really.") "I've always liked to think of meself as having me feet on the ground,' the drummer says, just in case there's room for doubt. "An obvious problem of becoming well-known, though, is that it has become more difficult for me to socialise normally... When we played at V96 [Pulp's last public UK appearance during the long "Different Class" haul] I went out and had a walk in a gorilla suit. Nobody took any notice of me at all. So that was quite funny... But it did all do me head in for a bit." People close to him, meanwhile, suggest that, perhaps as a corollary of the adulation from the public and the media he was, getting, Jarvis was suffering from writer's block. That his abrupt change in lifestyle had left him unsure of where his future subject matter might come from. As Damon Albarn acknowledged in a story about Britpop's tabloidisation in FACE 91, when you make a career - forge an artform - from the poetry of crappy places and commonplace things and ordinary people, this can be a problem.

"An obvious problem of becoming well-known, though, is that it has become more difficult for me to socialise normally... When we played at V96 [Pulp's last public UK appearance during the long "Different Class" haul] I went out and had a walk in a gorilla suit. Nobody took any notice of me at all. So that was quite funny... But it did all do me head in for a bit." People close to him, meanwhile, suggest that, perhaps as a corollary of the adulation from the public and the media he was, getting, Jarvis was suffering from writer's block. That his abrupt change in lifestyle had left him unsure of where his future subject matter might come from. As Damon Albarn acknowledged in a story about Britpop's tabloidisation in FACE 91, when you make a career - forge an artform - from the poetry of crappy places and commonplace things and ordinary people, this can be a problem. "The way I think of it is in terms of the placards you have in a hairdresser's window, with the pictures of the hairstyles that you can get inside. And they're in colour, but then they've been in the window for ages and all the colour drains out and you're left just with light blue - blue seems to be the last layer of the printing process and you're just left with these faded blue pictures. And it's like that, you know? It's like you're subjected to this glare of relentless scrutiny, and if you don't apply a bit of shade to yourself, then you'll just fade and eventually you won't have any personality left. So you have to keep something back for yourself. Which was never a problem before. I had loads left back for meself, because nobody was arsed about who I was. It wasn't an issue then. But it is an issue now. You have to remain a human being. I think that's quite important."

"The way I think of it is in terms of the placards you have in a hairdresser's window, with the pictures of the hairstyles that you can get inside. And they're in colour, but then they've been in the window for ages and all the colour drains out and you're left just with light blue - blue seems to be the last layer of the printing process and you're just left with these faded blue pictures. And it's like that, you know? It's like you're subjected to this glare of relentless scrutiny, and if you don't apply a bit of shade to yourself, then you'll just fade and eventually you won't have any personality left. So you have to keep something back for yourself. Which was never a problem before. I had loads left back for meself, because nobody was arsed about who I was. It wasn't an issue then. But it is an issue now. You have to remain a human being. I think that's quite important." Three years on, his personal and professional landscape may have changed beyond recognition, but the song remains the same: "In your mind you try to picture old people, and you think of the songs they play on Radio 2, and it's as if people are suddenly going to flip over and start listening to Vera Lynn records or something when they get to, like, their fifties. But obviously that's not going to happen, is it? You can see it on Radio 2 now, where they get all the stuff that's been rejected by Radio 1, such as Tina Turner and Eric Clapton. It's really going downhill.

Three years on, his personal and professional landscape may have changed beyond recognition, but the song remains the same: "In your mind you try to picture old people, and you think of the songs they play on Radio 2, and it's as if people are suddenly going to flip over and start listening to Vera Lynn records or something when they get to, like, their fifties. But obviously that's not going to happen, is it? You can see it on Radio 2 now, where they get all the stuff that's been rejected by Radio 1, such as Tina Turner and Eric Clapton. It's really going downhill. In its original formulation back in the day - 1995 - "Britpop" meant just four groups: Blur, Oasis, Suede, Pulp. Now Blur have -gone difficult" as Jarvis puts it, and Suede have plateaued, and Oasis� -Blur said they wanted what Oasis wanted," Steve Mackey says. -But I think the truth of the matter is that Blur didn't really want it. Because you've got to go out and just fight for it, and the Gallaghers were prepared to go out and do that, work their arses off non-stop. Most people realise it's not worth working that hard for. But the Gallaghers really wanted that thing, and they'd do anything to get it. You're never going to win against them on that, are you? They've learnt that money means power and they use it. I find it all a bit scary."

In its original formulation back in the day - 1995 - "Britpop" meant just four groups: Blur, Oasis, Suede, Pulp. Now Blur have -gone difficult" as Jarvis puts it, and Suede have plateaued, and Oasis� -Blur said they wanted what Oasis wanted," Steve Mackey says. -But I think the truth of the matter is that Blur didn't really want it. Because you've got to go out and just fight for it, and the Gallaghers were prepared to go out and do that, work their arses off non-stop. Most people realise it's not worth working that hard for. But the Gallaghers really wanted that thing, and they'd do anything to get it. You're never going to win against them on that, are you? They've learnt that money means power and they use it. I find it all a bit scary." "I remember when I was really young seeing George Melly on this telly programme," Jarvis is saying now as he leans on the bar at the Met. -He was saying that quoting surrealist poetry at a gang of blokes who were about to cave his head in had saved him. And being this knobhead with specs on driving this stupid little Hillman Imp, I found it very useful. Because it unsettles people. Once people get the smell of fear and know you're frightened of them, in a way it turns then on, and they'll really go for it. If you react in a way they don't expect you to, it unsettles the situation."

"I remember when I was really young seeing George Melly on this telly programme," Jarvis is saying now as he leans on the bar at the Met. -He was saying that quoting surrealist poetry at a gang of blokes who were about to cave his head in had saved him. And being this knobhead with specs on driving this stupid little Hillman Imp, I found it very useful. Because it unsettles people. Once people get the smell of fear and know you're frightened of them, in a way it turns then on, and they'll really go for it. If you react in a way they don't expect you to, it unsettles the situation."