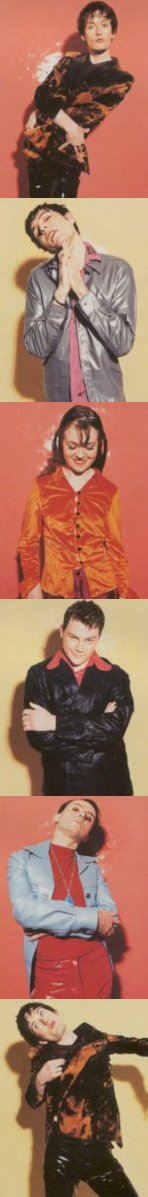

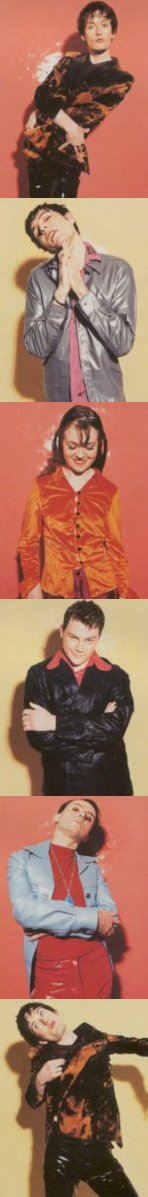

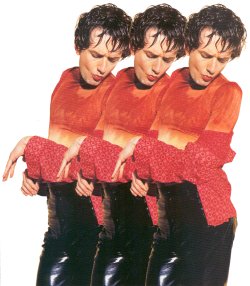

Words: Amy Raphael, Photographer: Peter Robathan

Taken from Face 66, March 1994

His name is Jarvis, his band is Pulp and he just might be the pop star to surface from the indie world's jingle-jangle Jacuzzi. Can this man bubble up better than Brett?

Eight o'clock on a Friday night and Pulp have had it. They're slumped on black leather sofas in a recording studio in north London looking dazed and slightly confused. A video of an experimental Channel 4 short sucks in their attention. Pulp are known as Sheffield's top (indie) glam band. But tonight they wouldn't turn many heads. They've been in front of the camera all day, posing and pouting for this story. Russell Senior (guitarist, violinist, sunglasses fetishist, Gary Numan clone) has gone home to see his new-born son. The most glamorous the remaining dedicated foursome get is when a few specks of glitter left on their faces occasionally catch the light and sparkle.

The video finishes, someone lights up a cigarette and Steve Mackay [sic] (smiley Latino-looking bass player with an interesting line in orange shirts) wiggles a bare toe. "Is it time for Brookside yet?" asks Candida Doyle (diminutive keyboard player) of Nick Banks (drums). Jarvis Cocker, sporting tight purple velvet trousers and a green blanket, decides it's time to do some work - he goes off to listen to a mix from the album Pulp have spent the last three months recording. Jarvis is long and stick insect skinny. Forget the new wave of new wave. Here's the new wave of new waif. Jarvis could be responsible for handfuls, no, hundreds of teenage boys fasting and fading away.

Jarvis Cocker has been in Pulp since the start of the Eighties, when he was in his mid-teens. He and Russell used to play during school lunchtimes, charging people to see them. Pulp have one of those indie histories (legal complications with their first label, Fire, resulting in their third album being sidelined for two years etc, etc) which should stay history. They signed to Island last year and next month release what they see as their first proper album. From the tape they play in the studio, they have lost their cheap indie sound, gained a luxurious, layered texture and somehow captured the energy of their live shows. These Marc Almond-style kitchen sink dramas are glam rock, camp electro disco, experimental pop songs. If this album doesn't do it for Pulp, Jarvis will probably have a nervous breakdown. "I've given rock 'n' roll the best years of my life," he says in a broad south Yorkshire accent, a wry grin crossing his face.

There's only so long a band can hold out, waiting for the recognition they feel they deserve. Jarvis says he has no desire to be lost in the indie section of record shops. "I'm not going to come out with that good old one bands love to say: 'We just do our stuff and if it sells, great.' We've never wanted to target a particular section of humanity. We've always wanted to be appealing to anyone who cares to listen to us. Sometimes we haven't been successful." Jarvis distracted himself from fantasies of fame by moving to London to do a film course at St. Martin's College of Art and "by the normal drugs and alcohol".

Towards the end of his course, Pulp released a single, "My Legendary Girlfriend", on Fire and NME made it single of the week. Then nothing. Last year it looked again as though their time had come, with the Seventies fad helping the likes of Suede and St Etienne along the way. But buying brown flared suits and bright crimpeline shirts from jumble sales - as they'd always done - wasn't enough.

Towards the end of his course, Pulp released a single, "My Legendary Girlfriend", on Fire and NME made it single of the week. Then nothing. Last year it looked again as though their time had come, with the Seventies fad helping the likes of Suede and St Etienne along the way. But buying brown flared suits and bright crimpeline shirts from jumble sales - as they'd always done - wasn't enough.

Nor was releasing two great pop singles, "Razzmatazz" and "Lipgloss", and an album of their collected works, "Pulpintro", enough. The music press donated space, gigs sold out, people discussed Jarvis' eccentricity and twisted tongue-in-cheek take on suburbia, growing up in the Seventies, relationships, sex, sex, sex. At the start of last year, Pulp supported Suede in France. These were Suede's first gigs outside England; Pulp had crossed the Channel dozens of times. The French audiences screamed for Brett, but they screamed equally loud for Jarvis, who wasn't even trying. Yet back home in Britain, it was Brett who stole the limelight for the rest of the year.

Jarvis has no answers as to why he's not yet the star he should be. Pulp effortlessly transcended the Seventies glam fixation intact. And now he feels things might be changing. For the better. "Doing this album means we can kiss goodbye to a period of our lives. And I'm also moving out of my council house in Camberwell to Ladbroke Grove. I haven't even seen the place I'm moving to, but it feels like the end of an era."

Jarvis Cocker is a performer. On stage he is an out-of-control puppet, arms akimbo, legs in size too small trousers jerking randomly. His conversation between songs is all sarcasm and irony. If Mark E. Smith ever went to a fancy dress party, he'd be Jarvis. In the house down the road from the studio where bands can stay during the recording, Jarvis sits cross legged on a sofa in the living room. He hold a champagne glass half-filled with neat whisky between elongated, bony fingers. While talking he looks into the fake fire, the artificial flames reflecting on his black rimmed, rectangular glasses. He occasionally turns and smiles, looks for a response to an anecdote or a joke. His lack of eye contact is disconcerting, his eccentricity anachronistic, his sexuality intangible. But his charisma, his mystery, his poise are familiar.

Jarvis, are you a natural star? "That's difficult for me to answer, isn't it, because if I say I am, then I'd sound very conceited. But I can tell you that I have always attracted attention, and for most of my life I didn't like it. Because physically I've never really conformed. I was dealt a certain look. As in tall and thin. My mother didn't help by making me wear certain clothes to school. We had a German relative and they used to send over lederhosen. I looked like an Alpine shepherd boy. I was seven or eight. Of course, in a school in the suburbs of Sheffield, that wasn't normal behaviour. I managed to cajole my grandma into buying me some normal shorts, and I'd change on the way to school. People would generally call me names and think I was odd. I didn't get beaten up because I could tell jokes, but I always wanted to fit in."

Punk happened, giving Jarvis the confidence that it was alright to be a bit different. When he was 14 or 15, he went on his own to see The Stranglers (no one else in his school was interested). He wore with pride a tie his mother had crocheted for him. He still didn't fit in. "I just realised that there was no way, even if I wore casuals, that I would be like everybody else. It just never worked, it never looked good. So in the end, I thought if you've got an imperfection, you may as well flaunt it and turn it into an advantage." He gets up to pour more whisky then sits down again, folding his legs beneath him like a baby giraffe. "As I've always worn glasses, I've always been called all the names under the sun - Elvis Costello, Harold Lloyd, Michael Caine. there must be a big Roy Orbison fanbase round here, 'cause I get his name all the time at the moment."

With all his (exaggerated) physical freakiness, Jarvis has found himself a surprising pin-up. A friend of mine can't help herself when she sees him on stage. "First gig, and my immediate reaction was 'yum, yum'. He's scrawny but very sexual. He's quirky. He's a poseur but he gets away with it. He knows what he's doing; he's not a 19 year old playing around with an image he doesn't understand. I like men who dress up without being effeminate." Maybe it's just not being macho. "I haven't got the facilities," says Jarvis. "I wouldn't know I turned women on... I've always got on quite well with women and girls. My dad left when I was seven, and I was brought up in a house of women." He appreciated their "much more realistic attitude", overheard conversations about sex and relationships and was put off both.

Prematurely disillusioned, self-conscious and shy, Jarvis put off sex till he was 19 and only did it then because he wanted to experience teenage sex. He's been thinking about virginity a lot recently because of Pulp's exuberant next single, "Do You Remember The First Time?". "We thought with this song we'd take advantage of having more money and do something more interesting. So instead of just making our own video as usual, we've also done a 15-minute documentary. I interviewed celebrities - Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer, Terry Hall, Alison Steadman, Jo Brand, John Peel - about their first time, what a letdown it was, how long it took them to enjoy sex. I have no regrets about the first person I had sex with. We were both virgins, so neither of us were under any pressure to perform. It probably took me a long time to get any good at it, to get reasonable at sex... I still don't know."

When Jarvis first moved to London, he couldn't deal with the city's anonymity, found it a trial to meet women and stayed celibate for three or four years. "Makes you appreciate it when you finally get round to doing it," he says, smiling and reaching for a cigarette. "I don't think sex is the be-all and end-all of life. I write about sex because I think it motivates people's actions a lot of the time. Not enough is written about the psychological dimension of it, that was what was hard for me at first, being quite reserved, being an inch away from someone. In fact, you're on top of somebody. You're both completely in each other's personal space and there's no escape."

These days, Jarvis has taken up a curious but an ultimately safe - if not the safest - approach to sex. He says it's more exciting and less awkward to send and receive dirty letters than to talk dirty in the flesh. "So if you misjudge, the letter can be thrown on the fire and it's not such a bad thing." Who do you correspond with? "I'm not telling you. It's a mutual arrangement. I'm not a promiscuous person. It's good to have little alternatives. It's someone who, um... they sent me a teasing letter, so I sent one back even more explicit. It's developed by degree to a certain pinch. Who knows what might happen one day. It's a nice thing; it's never happened to me before. I've never had pen friends, never been into writing letters." He catches a sceptical look on my face. "I'm not going to get them out and show you. I don't see what's so unusual about it." He frowns. "Maybe I'm disclosing too much."

Nine o'clock on Saturday night in the studio and Steve is fast asleep, curled up like a baby by the mixing desk. Jarvis is cutting an unlikely figure, playing table tennis. MTV is on silently in the background while the almost-completed Pulp album is playing. Candida is eating crisps and Smarties. Nick is sipping larger. They talk about capturing the live sound on record, and about working with Suede producer Ed Buller who they trust and who they reckon is "quite a good musician, whereas we're not really. He knows how to use all this brilliant Sixties and Seventies equipment that's really complicated." Like Jarvis, the band want their records to sell - "quadruple platinum in every territory" - so they can at least make another album. The songs sound epic, especially "His 'n' Hers", a look at suburban relationships, matching towels, sex on fake rugs, with Jarvis doing heavy breathing that would put Dennis Hopper's efforts in Blue Velvet to shame.

The big fight between Eubank and Rocchigianni starts on TV and the band jokingly bet on how many rounds it will last. Steve shouts and screams at the TV. Jarvis remains passive At the end of the fight he puts his black fake fur coat over his purple velvet trousers and purple shirt. There's no sign of glamour or glitter tonight. It's 11 o'clock on a Saturday night and Jarvis is going to bed.

Towards the end of his course, Pulp released a single, "My Legendary Girlfriend", on Fire and NME made it single of the week. Then nothing. Last year it looked again as though their time had come, with the Seventies fad helping the likes of Suede and St Etienne along the way. But buying brown flared suits and bright crimpeline shirts from jumble sales - as they'd always done - wasn't enough.

Towards the end of his course, Pulp released a single, "My Legendary Girlfriend", on Fire and NME made it single of the week. Then nothing. Last year it looked again as though their time had come, with the Seventies fad helping the likes of Suede and St Etienne along the way. But buying brown flared suits and bright crimpeline shirts from jumble sales - as they'd always done - wasn't enough. Sex On A Stick

Sex On A Stick