Pulp Culture

Pulp CulturePulp's Jarvis Cocker may be a pop showman par excellence, but his band's trenchant songs tackle the pain, the slow-burning crises, and the dead-endedness that the hoi polloi daily endure. And it's not a pose.

There's a way - a heavy-lidded, half-bemused, half-resigned way - Jarvis Cocker has of looking out of Pulp's videos that suggests he's trapped inside them. In the "Help the Aged" video, inspired by the Powell and Pressburger film Stairway to Heaven (a.k.a. A Matter of Life and Death, 1946), he's ascending in a stairlift to heaven, a thirty-four-year-old man sampling a humiliation endured every day by the old and infirm. In "This Is Hardcore," a bizarre melange of neo-noir and Busby Berkeley musical, he's the nonplussed human pistil at the center of a rotating whorl of scantily clad showgirls. Cocker's expression doesn't exactly say, Let me out of here, but it does say, How the f**k did I get in here in the first place?

Both songs come from the recent This Is Hardcore album (Island), Pulp's third since the twenty-year-old group's Britpop-inspired renaissance, and their eighth in all. The record continues the themes of sexual ennui and quotidian dreariness Cocker explored on 1994's His 'n' Hers and 1995's Different Class, but the sense of entrapment he evinces has never been more desperate: "This is the sound of someone losing the plot / Making out that they're okay when they're not," he warns on the opening track, "The Fear," which comes complete with '50s-style horror-movie sound effects.

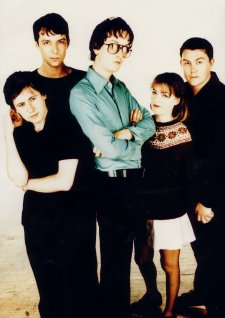

Not the smallest part of Cocker's achievement has been his gathering together of a group - Candida Doyle (keyboards), Steve Mackey (bass), Nick Banks (drums), and Mark Webber (guitar), replacement for the long-serving Russell Senior - whose musicianship amply complements his existential laments: turning, for example, one Don Juan scenario (the title track) into a sardonic penthouse rhapsody and another ("Seductive Barry") into a dreamy eight-and-a-half-minute smooch.

Central to Cocker's thesis is the idea that life, for the majority of people these days, is a dead end in which sex is a second-hand event and romance a source of perpetual regret. It's a snare, his songs imply, we've set ourselves by buying into the empty promise of transcendence that's offered by movies, TV, advertising, and porn - not in itself a new idea, but one given a lacerating Wildean update by Cocker's marvelous drollery and his breathy, conspiratorial delivery. Never a misery or a know-it-all, he's a rueful poet of social conditioning.

Onstage, Cocker is an emotive pop dandy who does things with his hands Shirley Bassey never thought of. When I met him in a downtown Manhattan hotel room, he was wearing his now permanent smoky sunglasses, a blue shirt, and an array of different browns. Jet-lagged but responsive, he sipped coffee and smoked, and made it clear he gives a damn.

Noel Gallagher [of Oasis] has said that seeing [Smiths guitarist] Johnny Marr on Top of the Pops crystallized what he wanted to do with his life. Was there any pop star that had a similar effect on you?

It was probably the Monkees, although I know that sounds stupid. The only decent records my mother had at home were Beatles records. I think my dad took the good ones with him when he left. Anyway, the rest of it was Blood, Sweat and Tears and crap like that. But the Monkees were on telly a lot and I used to fantasize about being a pop star. I was already thinking of the advantages. One of them was that you could pay someone to show episodes of The Monkees whenever you wanted. In a way, I achieved that ambition the last time we toured in America, when I bought The Monkees television series box set. I found out that some of those shows stand up, some of them are boring. Mostly I realized that when you fulfill an ambition you had when you were a kid, you're not that bothered about it anymore.

How did you get from watching the Monkees to forming Pulp?

I had this vague idea I wanted to be in a group, and I used to pretend to myself sometimes that I was in one - maybe because I was a slightly solitary child and it was a way of being in a gang. Two things coincided when I was about thirteen that gave me the impulse to actually do something about it. My mother was going out with a German bloke at the time, and I told him I wanted to learn to play guitar. He brought me a semi-acoustic guitar one Christmas - I've still got it. Then punk rock happened. I'd been thinking I'd have to learn how to play really well, but obviously the message of punk was that you just learn three chords in a week and you're away. I thought, Yeah, let's have a go at it. And I persuaded some friends to come to my house on a Friday night when my mum was out, and we started rehearsing.

Were you naturally musical?

I've never become a sophisticated musician. I can play chords and stuff. My sense of rhythm's not bad.

What has been the greatest influence on your lyrics?

In 1985 I fell out of a window and was hospitalized. Up until then, I'd been thinking of music as something you had to express on a high aesthetic plane, but when I was stuck in bed I had all this time to think. I was in hospital with quite a strange mix of people and I found out the things that are most pleasurable are small, ordinary things. I read Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which is about subjects like custom cars and surfers in California. Those things didn't interest me particularly, but there's something about the way he gets inside people and takes liberties. I guess, with expressing their thoughts. He's especially good on physical detail and what people are wearing. That set me on a different track with my writing. It's maybe been the biggest influence on my career. I'd always been disappointed with the disparity between what I felt I'd been promised by watching TV and listening to songs as I was growing up and what things were actually like when you experienced them. Generally, entertainment presents things in an idealized, romanticized way. It became my mission, if you like, to try to present things as I think they are rather than as what they're supposed to be.

You write a lot about how emotions change when they're mediated: particularly love and sex. It's the idea that if you turn a camera on an experience or try to make it measure up to fantasy, you turn it into a kind of pornography.

But I also believe that people nowadays are so used to the mediated version of things that when the real thing comes along it doesn't seem as real, and that's always been a bugbear of mine. To go back to my accident, I remember hanging from the window ledge and thinking, This is actually a dramatic situation, but it doesn't seem dramatic. In a film, there'd have been good camera angles and music heightening the tension of the scene, but of course there wasn't any of that, and it was actually a very mundane, pathetic thing that was happening. It was like my fingers were losing their grip, and I had to make a decision whether to allow myself to slip off or just let go. And I went, "One, two, three - let go." And then, bang. But the point is, I was mediating it even as it was happening. I don't know whether this is a common thing. I think it must be because people are brought up with a TV, and often you see things before you experience them. You see people kissing and falling in love on the telly before you get around to doing it yourself, and you can end up semijaded before you've actually done anything. That's why I like that film To Die For, where [Nicole Kidman] says, "What's the point in doing something if nobody's watching?" That's become true in our lives to a certain extent, but it's wrong, obviously. Somehow the cart has got before the horse.

As somebody who's figured this out, are you still as prone to it as anybody else?

That's the unfortunate thing, you see. I could say I worked this out years ago, but I still fall for it. Life would be pretty drab if everything was down at a pavement level all the time, and so for whatever reason I still find images seductive. I guess you have to try to appreciate them as an illusion rather than as something to aspire to.

Why do you think it took so long for Pulp to be accepted?

I think it was a combination of different things. I find some of our early stuff very hard to listen to. I actually find all of our music hard to listen to because it's personal, and once it's recorded I don't really want to hear it. Anyway, we were stuck up in Sheffield, and I had this idea that there was no reason to go down to London: If we were good, we'd get discovered anyway. But then we did move to London, which showed me a bigger version of the world, and that had a big effect on the music. And because I was doing a film course as well, I became relaxed about being onstage and that made us more palatable to people. Also, we just improved.

There seemed to be a shift in the way you sang. On the early Pulp records your singing was flatter -

...flatter as in "out of tune."[laughs]

- but by the time of Separations [1992], your voice had taken on a certain drama, and it made a huge difference. Was that record the turning point?

In a way, but that record was a pain in the arse to do. It was done in my second or third term of college, and I managed to do a degree in the time it took for that record to come out. Some of the songs were a year old before we even recorded them, so it was very frustrating. In the interim, rave had happened to me. I surprised myself by how much I got into it. It was real exciting, you know. There was a covertness about it being held in these illegal places and there was the cloak-and-dagger thing of having to get the tickets from a dodgy bloke with a mobile phone. . . . It was just what I'd always wanted going out at night to be like. There were no pop stars or anything. It was just music, and the people who were dancing were the stars. Nor was there any of that desperation of trying to cop off with women, and it wasn't about people punching each other because they were drank. It made rock seem completely outmoded, and that informed our music. We even had a vague go at doing a house track, "This House Is Condemned," but it wasn't an entirely successful experiment.

How many of your songs are actually based on personal experiences?

This is something that used to get me into trouble with my girlfriends. Obviously I know the cutoff point, where the imagination takes over from the real thing that triggered it, but people listening to the songs don't know that. Usually, something will happen that gets me thinking, and I think that situation through to its logical conclusion. So the initial third or two-thirds of the situation I'm describing will be real, and then for some reason I neaten it out and make it into a scenario. It's like in "Common People," where the woman says, "I want to sleep with common people like you." Well, the woman in question didn't say that. That was just because I fancied her, even though I thought she was a bit stupid. But she did say she wanted to live like common people. I just projected my fantasy on top of it.

Do you think there's a misconception about you as an ironist?

Ironic - that's the thing that I hate. It really irritates me because it implies a detachment and a kind of high-and-mighty viewpoint on things. But all the songs come from real experience, and the only reason I feel I've got the right to write about stuff is that I'm involved in it. And my trying to write about it is a way of trying to make sense of it. I do see little ironies in life, but I haven't got an ironic detachment to my material. If I did, I wouldn't be able to get excited about it. It would seem like a pretty boring, pointless exercise to take a scientific approach.

There's a line at the end of "The Day After the Revolution" on the new record where you say a lot of things are over, including irony...

Yeah.

Is that you refuting irony?

I'm saying, "Stop fucking writing about it, all right?" I don't think there's much time for irony in the late '90s as we hurtle toward the new millennium. I think there's a kind of desire around to work things out, and there's no point in being detached from such a big milestone as the end of the century and the start of a new one, whatever you think of its significance.

Did people think you were being ironic when "Help the Aged" came out in Britain?

Yeah, they did. But the song was born out of a very real fear of dying. Everybody knows they're going to die eventually and nobody likes it - or the thought of getting older and not being able to do what you used to do. Because we live in such a youth-oriented society, I think people are actually more scared of not being young anymore than the thought of getting old. They don't perceive very much that's attractive about adulthood, so they extend their adolescence to ridiculous lengths, myself included. I guess when I first came up with the line I found it a bit funny, but often my way of trying to deal with things I'm worried about is to turn them into a song, and instead of hide, confront them. Doing that hopefully helps me get through. I've always been aware of aging, because success did come quite late to us and it's difficult to hold onto your dignity in the pop-music business. If you're older, it gets harder. You're reminded of your age a lot more than other people, because you're always having to look at photo sessions of yourself and think, Jesus, I look fucking rough in that.

Do you think your songs are political?

They're not political like Billy Bragg's. But I'd be surprised and offended if somebody listened to our songs and said, "Oh yeah, he votes Tory." I hope there's a humanity to the songs that shows I'm more inclined to a socialist view of things.

Listening to the new record, I got a stronger sense of -

...panic?[laughs]

- and despair about how people can fritter their lives away: There's that line, "I could do anything If I could only get 'round to it." You're also pretty scathing about the pointlessness of the male success ethic.

Traditionally, men are more driven to success than women, and if you're successful, that makes you more male, because you're the top dog. But the things that men aspire to remain the same throughout their lives. They play with toys: the Matchbox car becomes the Ferrari. As it says in the song "I'm a Man," if it's all about driving a fast car, then I'm not really interested. I wish there were an alternative manhood. Maybe there is one because I often get referred to as camp. I just think I'm not macho - that's it.

What is "Seductive Barry" about?

That song had a long gestation. It's called "Seductive Barry" because we thought it sounded like a Barry White song, I was singing through a vocoder but I didn't have any words for about four or five months. The producer was getting irritated and he kept saying, "When are you going to write some fucking words for this song?" I was worried about it because, I didn't want it to be a retread of a song like "My Legendary Girlfriend" or "F.E.E.L.I.N.G.C.A.L.L.E.D.L.O.V.E," which had the same kind of mood. I didn't want it to be like a Barry White song where I'd be saying, "Baby, I'm going to do it to you all night and I'm so fucking hot," and the woman just going, "Year, you are." It had to be about meeting on a more even footing, so I came up with the idea of getting a woman's voice to be part of the song instead. That's why we got Neneh Cherry to sing on it. I wrote the words quickly once I got the idea: They're about meeting the object of your desires, and how you deal with a fantasy becoming a reality, Blokes love to look at pictures of naked women in magazines and papers, right? And they say to themselves and each other, "I wouldn't mind giving that some," but if they were actually put in a room on their own with the women in those pictures, they'd probably just blow it, because they wouldn't know what to do. The song's all about having the balls to go through with that situation.

There's a suggestion in some of your songs that sex is often a letdown.

I think sex is great, but it's not inherently great - like it just happens and it's fantastic. You have to make it that way. Maybe more than any other sector of human experience, there's a lot of messing around with the fantasy of sex than what it's actually like. In "Seductive Barry," it was important to me not to undercut the idea of sex by having a sarcastic payoff line. That's why it ends, "If this is a dream then I'm going to sleep for the rest of my life." It's like, it's all right, it feels good, so I'm going to keep doing it.

Do you think sex is best when people are in love?

I don't know. The idea of sex without responsibility is a male fantasy, but love gives it a responsibility. I think there has to be something between the two people. Sometimes sex can work if you don't even like each other that much. There can be a perverseness in it that makes it quite exciting. But there has to be some emotion. If you're just not bothered, it's no good.

On "Dishes," you sing "I am just a man but I am doing what I can to help you." Is that a genuine feeling you have?

Yeah. That song came out of the idea that small acts of heroism done in private are, in a way, more meaningful than visible achievements done in public. You can get glory and applause and awards for things done in public, but you don't for just helping somebody out on a one-to-one level. You just do it for the sake of it, because you want to do it. That's what that song's trying to be about. I was really pleased with it. Just after we'd finished it, I went to see that film Nil By Mouth, which is very harrowing, and it made me really glad I'd written that song because they seemed to key in with each other. The man in the film is so brutal and so unwilling to connect with his wife in any way. It's not really Oasis's fault but there's been this whole new lads thing in the U.K. that has endorsed treating women like shit again. At first it was a kind of semi-ironic thing that followed political correctness, but in the end it got taken on board and then turned into thuggery. Nil By Mouth showed where all that leads. It seemed to crystallize what had been going on, although I think that phase is over now. Or I hope it's over, because it's led to a lot of distasteful stuff.

It's unusual to see someone writing pop songs from a compassionate viewpoint without getting all sanctimonious and holier-than-thou. Somehow, you pull that off.

If people get a bit successful, they often turn into monsters and invite catastrophe because it gives them material to write about. It's always a game that you play with yourself, but you have to remember it's more important to be a human being than it is to be an artist.