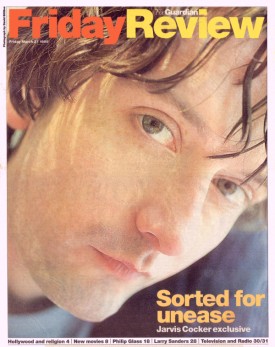

The Friday Review Interview

The Friday Review InterviewJarvis Cocker is one of rock's great kitchensink lyricists, so it was fitting that our first meeting took place in a kitchen. It was late 1992, at a party in a south London council flat. Cocker lived a few streets away, in a council place of his own, so he'd turned up with a couple of members of the not-yet famous Pulp. He was without doubt the oddest-looking person there, clad head to toe in polyester and towering over everyone else as he leaned against the washing machine.

Feeling rather sorry for him, I struck up a conversation. His taste in clothes suggested he wouldn't be averse to a spot of naffness, so I invited him to the Shakin' Stevens gig I was reviewing the following week. I had the idea I was doing him a favour, a notion humiliatingly shattered when Cocker ("his real name, apparently" I noted in my diary) failed to ring on the appointed day.

Anyway, it made a good anecdote three years later, when he became one of the most famous people in the country. His "interruption" of Michael Jackson's self-aggrandising performance at the 1996 Brit Awards was overwhelmingly approved by the public and Cocker became a hero overnight. He had been riding high anyway, with Pulp's 1995 album Different Class having topped nearly every critics' poll, but the Wacko Affair made him Britain's favourite pop star. He was adored by kids and grannies, Farah slacks became almost fashionable and he even became a waxwork at Piccadilly's Rock Circus. Life doesn't get much better, eh?

And now, March 1998, he's loping into a French café in Islington, and it's almost too much of a cliché, but he's actually clutching a Farah shirt. It's limp black nylon, and seems to have come straight from a jumble sale. Does he plan to wear it for the post-interview photographs? "I wouldn't wear this," he replies, affronted. "It belongs to the guitarist." But of course - the royalties from the two millionselling Different Class allow him to frequent a better class of jumble these days. Even so, the result is the same. The woman's cardigan draped around his girl-sized shoulders may not be Farah, but both it and his crimplene half-flares are authentically, Cockerly cheesy.

The new issue of Vogue proclaims that Jarvis's look is "over", but no one appears to have told him. If they did, it's unlikely he'd take any notice, for his eccentricity is deep-rooted and not subject to fashion's vagaries. Had he not been eccentric - a quality the British profess to cherish but in practice just about tolerate - he might not have had to wait 13 years for success (the time between Pulp's first Radio 1 John Peel session, back when they still lived in Sheffield, and their first top 20 album, His 'n' Hers). On the other hand, had he been as ponderously normal as Noel Gallagher he couldn't have written Common People, Sorted For E's And Wizz or a handful of other songs that are among the best ever recorded by an English group.

He now has public licence to be as eccentric as he likes and, indeed, is expected to be. When his breakfast yogurt arrives and he observes "They give you a lot of yogurt here", the waitress squawks like it's the funniest thing she's heard in months. What's it like when people expect you to be Jarvis all the time? "It's just part of the process of being well-known, you're defined by public opinion," he says in a mellifluous voice more suited to a regional newsreader. "You end up looking at yourself from the outside, very schizophrenically. I'd never wanted to construct a public persona because I used to pride myself that what you saw was what you got. But when that bloke did me on Stars In Their Eyes I thought, if I can be pigeonholed that easily I might as well be dead because who's going to listen to me any more?"

He did you perfectly, though. It's just a shame he was beaten by Olivia Newton-John. "He had all the moves," he nods, referring to the spasmodic wrist action that serves as dancing. "My immediate reaction was to say, Right, next time we play I'm not moving at all onstage, but then I decided that if anyone has a right to those moves it's me. I made them up because I can't dance normally."

Because fame came late - he looks far younger than 34 (he'll be 35 in September) - Cocker has a conflict with it. He's old enough to be cautious with his new-found wealth, still riding a bicycle and living in a rented apartment (he claims he can't afford to buy a place because royalties are democratically split with drummer Nick Banks, keyboardist Candida Doyle, bassist Steve Mackey and guitarist Mark Webber). But he couldn't resist sampling what he calls "show business", accepting virtually all of the many party invitations that came his way.

Not great for his earthy Northern image, consorting with the Tara Palmer-Tomkinson posse, and questions were practically asked in the House. "I thought, maybe this is what I've got to do now," he says in his own defence. "I was a novelty, so I got invited to all sorts of things. That's what does me in about show business, the way the ramparts are really built up to prevent you storming the inner sanctum, but if you do get through, you're suddenly part of the showbiz family. In the end it just wasn't for me, because those people just talk about nothing and I can't stand that."

He's no longer hanging out with Tara and friends (though she was invited to a party this week to launch Pulp's new album, This Is Hardcore), but continues to be a world-class party animal - though not for reasons you'd expect. "I go out because I can't stand my own company. I get on my own nerves. That's why I can't live on my own. I've always disliked myself quite intensely, and I'll do anything to avoid thinking." But why? He says he doesn't know, but you have only to listen to The Professional (B-side of current single This Is Hardcore) to realise he's not exaggerating. "Cocker is short for a sucker of..." goes part of the chorus, a mere million miles from "Sing along with the common people".

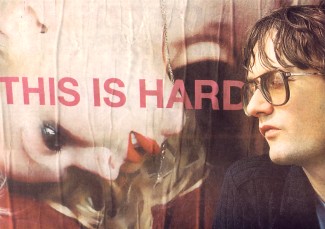

"The Professional is probably the biggest dose of self-loathing I've written recently. I wasn't feeling very good about myself at the time." The toll exacted by fame and drugs (more of which later) is there for all to hear on the new album. Those who loved Different Class for its vibrancy and wryness are in for a severe shock, because rarely have confusion and misery been expressed so palpably on a pop record. That's not to say it isn't magnificent, just that it has no parallel in the Pulp catalogue. "This is the sound of someone losing the plot/Making out that they're okay when they're not," runs the first track, The Fear, and it carries on from there. Help The Aged, a low-key single release last October, warns: "One day you'll be older, too... you may see where you are headed and it's such a lonely place", while Glory Days seems a clear warning about drugs: "I did experiments with substances but all it did was make me ill".

Of the last, he's understandably cagey. There have been music biz rumours about drugs for the past year, but he says only, "It's not surprising people take drugs. Reality can seem disappointing compared to what you see on TV, and drugs push you closer to what you see on the screen." For what it's worth, this particular morning he's clear-eyed and perfectly lucid. This Is Hardcore's most disturbing and magnificent number is the title track. More a suite than a song, it's about the stages of watching a porn movie, from "You are hardcore, you make me hard" to a climactic "What exactly do you do for an encore?" It's not the content, graphic though it is, that disturbs but the utter lack of pleasure in Cocker's voice. That could account for it going into the chart at a disappointing 12 this week, their lowest new entry in four years, but it is nonetheless one of Pulp's most stunning songs. So there you are - the first chart single directly inspired by pornography. But now isn't the time to spar about feminism, because Cocker has set aside his half-finished yogurt and is earnestly explaining himself.

"Porn's on the telly when you're on tour, and I got interested in the way people look at people in porn films, just as objects. Men look at the tits and women look at the... [his voice trails off] I mean, there's not much empathy going on. It's typical that I'll think about something in a really inappropriate way. I'm not into it erotically, because once you've got over the surprise of seeing a penis going into a vagina it's boring and mechanical. I'm just making a study of the human side of it. It's the first time I've ever made, shall we say, a thorough examination." Behind the slightly tinted lenses he's suddenly 14 and a half... Can you recommend any flicks?

"I don't know the names," he says dryly "You see the same faces all the time, though." It's a long way from E's, Wizz and Common People, but that, presumably, is what fame does to you, especially if you're a sensitive soul who never believed you'd actually get here. But as he hastens to point out, the LP ends on a hopeful note, fading out with Cocker dreamily murmuring, "The answer was here all the time." The bad times that spawned the songs are behind him now, and despite his "self-loathing" he seems chipper. More than chipper; positively friendly, in fact, as he sups a tureen of cappuccino and explains why his T-shirt has a sad-eyed puppy-wuppy on it (something to do with getting some made for a video, not using them, and being stuck with 24).

"The way to get through the things that were frightening me was to actually write a song about it. The Fear was about panic attacks. Certain decades have certain illnesses, like with the eighties it was ME, and in the nineties it's panic attacks. I wasn't happy at the time I wrote it, and I was thinking more than I ought to about whether it was worth doing another album at all because I felt like Different Class had said it all. It frightened me, to think that might be it. I find it funny, that song, because it's so over the top - your sex life is gone, there's not just a monkey on your back but it's built a house there. It's funny because it's so extreme. I hope the album does really well," he adds with his soulful-owl gaze. "It's done its therapeutic duty for me, so I hope people get something from it."

Even if they don't, he's been commissioned by Channel 4 to make three documentaries about "outsider artists", which should help him realise his eventual ambition of leaving music to direct films. And he can dine out on Michael Jackson for the rest of his life. No one will ever let it lie - even Jacko's nephews, the band 3T, mentioned it in an interview recently. "That whole clan has really weird eyebrows, like they're tattooed on," he muses tangentially. "Ironic that you become more famous for a random silly act than anything else. But it was nice that people agreed. To this day, people. shout out to me [Cockney accent], 'Nice one, Jarvis!'".

And rightly so. British rock would be a poorer place without his synthetic fibres and his singular vision.