Nothing Left To Write Home About

Nothing Left To Write Home AboutOnce he sang about failure and disappointment. But now he's got it all. The big house, the It Girlfriend - even a TV series. About art. Whatever happened to the common people?

Jarvis Cocker, the pop star who wishes that he wasn't, was on a mobile phone when I walked into the bar. "Ta ra," he said into the receiver. To me, he said, "It's not mine. I'd hate you to think it was mine. It's not you know." And he flicked the little Nokia across the table. Jarvis Cocker is not a mobile phone kind of person. He doesn't read magazines either - not any more. Or the 'art bits' of the newspapers. He was sick of having his head 'littered with second-hand reviews' of things he was never going to see or read. He'd find himself in the pub discussing a film he hadn't watched, "but you've read a review and you say, the first half hour is fantastic, one shot, amazing. And then you think what the fucking hell are you doing? It's not on."

So he's given that up, along with smoking ("I woke up on New Year's Day feeling dog-rough") and television. Timing wise, giving up television isn't tactful: he is supposed to be promoting a three part series, narrated by him, on Outsider Art, for Channel 4. So why give television up now? "Because it's shit." But what about his programme? "I'll set my video for that." Take it he hasn't got cable? He looked sheepish. "Well I have..." He faltered. "But only because there's no aerial on the roof of my house, so it was easier." He glanced at the door as if to check we weren't being watched. His voice went very quiet. "And you got a good deal with the phone line as well."

Poor old Jarvis, or Jarve as he refers to himself (as in "so I thought, Jarve..."). He spent those long years in Sheffield trying to make Pulp happen, refusing to compromise, being different from his friends and neighbours with their mortgages and steady jobs, standing out in his geekish clothes and funny glasses, writing his defiant songs about supermarkets and bad sex and failure. And then suddenly, after a decade on the outside, at the age of 32, he made it. Different Class, the album of 1995, sold a million copies and went to number one. Jarvis became a Britpop star. Girls screamed at him, boys imitated him, London swung. Jarvis got to go to happening parties and have affairs with make-up artists and preside at award ceremonies - making one last stand for rebellion when he danced satirically on stage during Michael Jackson's Earth Song at the 1996 Brit Awards and was interviewed by the police.

Slowly, when the novelty wore off, he realised he'd achieved all the things he'd despised - all the "bourgeois shit" of middle-class, even worse, celebrity, life. Could he be called "different" anymore "I've got a pepper grinder," he told me mournfully. "That's pretty middle class, isn't it?" He's just bought a house to put it in, a five storey place in Hoxton, the hip-hot neighbourhood that dangles off the end of Old Street in London. We met around the corner, in a bar where people are too cool to notice a pop star in their midst, and where even at teatime it's too dark to spot them. Everyone in there looked like Jarvis Cocker.

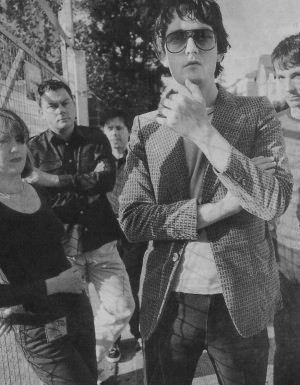

"It's all right here," he said, 35, 6ft 4in and spindly, his greasy fringe flopping above mauve-tinted specs, his gawky limbs shifting his ill fitting charity shop threads as if they were still a bit itchy after the wash. When he wraps his tiny striped scarf, like bootlace candy, around his neck, and pops on his matching bobble hat, he looks like the elusive hero of the Where's Wally? children's books. But unlike Wally he has high cheekbones and soulful eyes. Unlike Wally, he's extremely sexy.

His appearance is clearly very important to the inner Cocker. He used to find it traumatic being recognised, and told a story about being chased by a bunch of kids through a Sheffield shopping centre. "I ended up hiding behind some tights in Marks & Spencer." But surely a disguise would be pretty easy, he'd only have to wash his hair and wear a hacking jacket? He looked appalled. "Get lost," he said. Cocker, who says with some self-mockery that he's been "terribly tainted" by growing up in "our society", does everything he can not to "compromise", or to "alter" himself to fit in. He gets himself in quite a pickle ideologically. Take his house. He's always felt "claustrophobic, uncomfortable" with the idea of property. "And having grown up in the punk rock era I always considered it, like, a bourgeois sell-out to have a mortgage. But in the end I decided to admit that I had to get one, or you'd end up in a hostel. There was no alternative." What about renting? He gave me a funny look. "Somehow that didn't seem to be right," he said.

The TV series came along at just the right time. Since he discovered a book on the subject of Outsider Art during his time at St. Martin's College of Art (film studies) in the late 1980s, Cocker has been interested in the kind of creativity "in which you make things and decide what they mean afterwards, rather than analysing and talking about things and then doing fuck-all". The artists he interviewed are outside the mainstream, marginal, arguably mad, characters who erect hundreds of totem poles in their gardens, or cover their walls with broken crockery. "They're more in touch with the basic things inside them, rather than being informed by what they've seen on television. The art comes from a basic need to make things rather than a desire for attention or glory," said Cocker - enviously perhaps. "They're more real."

They gave him hope. "It wasn't like I was travelling around looking for home decoration tips," he said in his flat Sheffield accent, in which irony can sound like bolshiness. "But I was looking for a way to see how your living space could be something you kind of express yourself with, rather than a straightjacket, rather than I'm just like my parents, I've sold out, this is it." (Bit unfair on his parents this: his mother brought him and his sister up alone, emptying fruit machines to get by, after their father went off to Australia when Jarvis was seven. She also made him wear lederhosen to school, so perhaps she's not entirely blameless.)

Anyway, he looked at a lot of houses; most of them required to compromise, but the one he finally chose "allows me to be me, but with more space to be me in". Five whole storeys in fact. "I've got a lot of ambitions," he said with a cackling laugh. He's very earnest about himself but sometimes you suspect even that's a bit of a pose. He and his lodgers - "I'd go insane if I lived alone, all you'd be left with is your thoughts" - threw a party before Christmas and it was a real test for his new middle class instincts. He winced. "In the end I thought fuck it, stop even thinking about putting polythene down in the floor. It's only carpet."

Cocker says he has a lot of "morbid thoughts", that his mind works in "dark ways". The jacket he's wearing, bought from a thrift shop, had library stubs for books about death in the pocket and a ticket "for some kind of Philharmonia concert" and he's made up a story "about this bloke who found out he was terminally ill and splashed out on a ticket for his favourite piece of music". Once he found a hairbrush in a hotel - "it was a good one so I kept it" - but it had white hairs on it and he started thinking about "this old couple who saved up for this holiday, this lifetime of waiting". In the end, he had to throw it away. "As you can see," he added with a wry smile and a rare use of eye contact, "I didn't use it very often." He brings the same pessimism to his own behaviour, notably his "party period" ("hammered most of time") between '96 and '97, when he was still thinking, "ooh they've let me in... There's Nicholas Parsons within spitting distance. As with most things though, the sheen of it wears of pretty quickly and you find it's chipboard underneath, not mahogany."

He got most heated with self-loathing when he recalled the time he was photographed shaking hands with a man dressed as Action Man "at this horrendous publicity junket and I was thinking, this really isn't what you should be doing Jarve, you should rethink". Or at being placed, in a gossip column, at the Starlight Express 10th anniversary party. "No, no. The idea that I would go within a mile... Andrew Lloyd Webber is bad enough, but Starlight Express... it makes my flesh crawl so much and the idea that I would have gone voluntarily to that. I never got that bad. Honest. I have done some sad things, but I never went that low."

On the future of Pulp he is circumspect. Last year, they brought out their third album [eh?!], This Is Hardcore, to disappointing sales. Cocker said: "Last year wasn't the most pleasurable year of my whole existence. It was like, okay then, you don't like me as much as you used to. Okay, I can handle that. WELL, I THINK IT'S GOOD. It's obvious that some kind of change in public taste has occurred. You just have to accept it." Will they be together forever? He got out a little white pipe from his jacket pocket - containing a nicotine capsule he told me - and took a smokeless suck. "No point staying married to somebody just because you can't be bothered to make the effort to find somebody else," he said. (He claims not to be in a relationship, but it is said that he recently left his long-term girlfriend, a psychiatric nurse, for the actress Chloe Sevigny.) "Same with a band. If we've still got something interesting to say we'll keep doing it..."

Cocker used to sing about failure and disappointment. Is it hard finding the same inspiration in success? "Well, yeah, yeah it is. Because if you've written a song called Common People which is about people slumming it and having these silly ideas about pretending to be poor when they're not, it would be pretty dismal to do it yourself. But then again..." He took another dry puff. For a moment, he looked lost. "There isn't much I find interesting to write about in middle-class life".