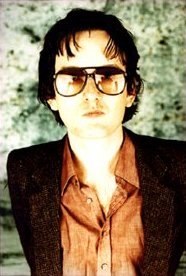

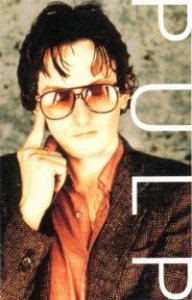

Words: Peter Murphy, Photographer: Stefan De Batselier

Taken from Hotpress, July 1998

When Pulp released the obsessively carnal This Is Hardcore, it was widely touted that the band's main mover, Jarvis Cocker, had lost the plot entirely. But Pulp are back on the road now and Cocker is in fine form - as eloquent when talking about pornography and sex as he is reflecting on the vagaries of the press and his relationship with his father.

Jarvis Cocker sits in the debris of his Oporto hotel room, desperately trying to cram his belongings into a suitcase before moving on to the next stop on Pulp's tour of European festivals. "My room is a shit-tip and I'll have to tidy it up," he explains. "I'm off to Belgium today. For me sins." Band and crew are leaving in less than an hour, we've an interview to conduct, and to aggravate the situation, somebody's frantically rapping on the door. "Who is it?" an irked Jarvis demands in that droll Sheffield monotone of his. "I'm doing this interview!"

Jarvis Cocker might be a wanted man, but he's also a relieved one. The band's headlining slot on the previous Sunday at the Glastonbury Festival went well, with the "difficult" material from the group's contentious This Is Hardcore album making a successful transition to the live stage, particularly the monolithic title track. Glastonbury occupies a significant place in Pulp history because, as Jarvis acknowledges, it was the band's last minute and highly successful stand-in slot for The Stone Roses in 1995 that helped propel them into the big league.

"We were pleased with it, because to go back and do it again seemed quite nerve-wracking," Cocker admits. "You could say that it made you - and it could've broke you. Some people have said that they find this record difficult to get into, and then there's been loads of crap written about me being a hopeless drug addict who masturbates in front of porno films all day, and generally thinking that we've lost it, so there was quite a lot to prove, do you know what I mean?"

I do indeed. Much has been made of the fact that This Is Hardcore hasn't sold as well as its predecessor. The new album did enter the charts at number one, but it sold only 50,000 copies to get there - hardly peanuts, but Different Class shifted 133,000 units in its first week. Certain parts of the press have decreed the record's performance as emblematic of the decline of the British record industry in general, while others are zoning in on its subject-matter as proof of Jarvis Cocker's apparent descent into cloud cuckoo land.

Granted, Hardcore is less of a pop masterpiece than its predecessor, and the quality of the songs does waver at the two-thirds mark, but it's still a record crackling with epic grandeur, from the Bowie-esque nervous breakdown of 'The Fear' to the creepy carnality of 'Seductive Barry'. The new material is undoubtedly dark, but sales figures are down because of a combination of factors: a marked absence of hype, few obvious singles, and no tour, promotional or otherwise, to boost the album's profile at the time of release. And, for the record, the man speaking to me on this hot July morning seems in full possession of his marbles.

"It's only a record, innit?" he sniffs. "God! When the last Oasis album came out and there was a lot of hype about that, I mean, ridiculous, it got written about in national papers and that, with people having to sign affidavits not to play it for anyone else, and I think that really turned people off. It's better to let people make their own minds up about it. And I always knew that this record was going to take longer for people to get into, because it doesn't deal with particularly pleasant subject-matter. But in the end, it was the only record that we could make at that particular time. Things had changed."

However, Jarvis didn't just annoy the record label by refusing to follow corporate promotional strategies: guitarist Mark Webber has gone on record as saying he's no great fan of either the album's title track, or the most recent single 'A Little Soul'. Indeed Webber went further last March when, in effect, he accused the lead-singer of refusing to listen to saner counsel. "Recently it's been a case of Jarvis' will overriding everyone else's common sense," he observed ruefully. So does Cocker believe that a dictatorship is necessary in order to get the trains running on time?

"Eh, yeah, it's always a fine line, and I hope I'm not too much of an arsehole," he concedes. "Like for instance, I went off and did this Channel 4 film (Cocker co-directed a series about "outsider artists" that will air next year) immediately after the album came out. I know Island were completely horrified by this, even though I told them about it, four months in advance. But when the reality of it hit them, they were very done in. But for me, I knew that I had to it at that time, because it was such an involved and slightly painful process making the record, and I knew it was very important for me to go off and do something else, on which the band had no bearing at all. But then I was meeting these people in these weird and wonderful places out in the middle of nowhere: they have no contact with the outside world so they don't know who you are, you have to relate to them on a completely normal human level, there's no PR to go in and smooth the way for you, all this kind of shit. Going out and seeing people who create these things just because they want to, and they can't even define why they do it most of the time, that was important as well. I could see how it looks bad from the outside if your album's taken ages and then you fuck off for two months when it comes out, but to me it made perfect sense."

"Eh, yeah, it's always a fine line, and I hope I'm not too much of an arsehole," he concedes. "Like for instance, I went off and did this Channel 4 film (Cocker co-directed a series about "outsider artists" that will air next year) immediately after the album came out. I know Island were completely horrified by this, even though I told them about it, four months in advance. But when the reality of it hit them, they were very done in. But for me, I knew that I had to it at that time, because it was such an involved and slightly painful process making the record, and I knew it was very important for me to go off and do something else, on which the band had no bearing at all. But then I was meeting these people in these weird and wonderful places out in the middle of nowhere: they have no contact with the outside world so they don't know who you are, you have to relate to them on a completely normal human level, there's no PR to go in and smooth the way for you, all this kind of shit. Going out and seeing people who create these things just because they want to, and they can't even define why they do it most of the time, that was important as well. I could see how it looks bad from the outside if your album's taken ages and then you fuck off for two months when it comes out, but to me it made perfect sense."

Pulp's story is like few other in the annals of pop. The band began in November 1981 in Sheffield, recording a session for John Peel while Jarvis was still at school. The bespectacled, beanpole-built Cocker, who had been bullied as a child (sewing a germ of rage that would fester for years before finally flowering, with spectacular results, in 1995) spent his early 20s as a film student, working in a nursery for deaf children, and floundering on the dole before Pulp finally began delivering on their promise with late '80s singles like 'Dogs Are Everywhere' and 'They Suffocate At Night'.

The current line-up came together in 1992, but it was their 1994 Mercury Prize-nominated His 'n' Hers, the group's third full-length album, that finally signalled their arrival. Featuring gritty (sub)urban vignettes like 'Babies', 'Joyriders' and 'Lipgloss', the record was described by the Sunday Times as being "Mike Leigh set to music". Indeed, Pulp keyboardist Candida Doyle's mother, who starred in the promo film for 'Do You Remember The First Time', had appeared in two Leigh films.

However, it was the release of the classic 'Common People' in 1995, followed by Different Class late that year, that established Pulp as probably the most important "English" English group since The Smiths. Different Class remains an astonishing record, by turns vicious, tender, vindictive, funny and empathetic. Jarvis emerged as a bona fide star, a sex-crazed avenger in NHS X-ray spex who, through songs like 'I Spy' and 'Pencil Skirt', took the class war into the bedroom, exacting revenge on the rugger-buggers and brick-shithouse snobs who tormented him in his youth by drinking their brandy and screwing their girlfriends. 'Common People' was one of the most savage political and personal put-downs in pop history, with Cocker spitting the most withering lyrics to hit the charts since Dylan's 'Like A Rolling Stone' over an epic electro-glam arrangement.

Equally glorious was the heartfelt compassion in tunes like 'Something Changed', 'Underwear' and 'Live Bed Show'. On that album, Pulp, who always had more in common with the art-rock fraternity than the dullard guitar bands, showed up the majority of their Britpop contemporaries for the jingle-jangle chancers they were. If these anthems harked back to an England of yore, it was the kitchen stink realism of the late 1950s, not the swinging optimism of a decade later.

"In many ways Different Class was a bit like our first album because it distilled a lot of things from my life that I'd always been trying to get across," Jarvis reflects. "There was something exciting about that time. I don't like the word Britpop, but that's what it gets called, this sudden boom of interest in what had previously been alternative music. And it was exciting, it felt like, 'Yeah man, you're storming the barricades, you're getting into the arena where normally just the cheesemaster's allowed to live'. And it was like a kind of revolution taking place. And then of course, the dust settles from that and you find that you've just got a new establishment, and I didn't want to be part of that establishment. I've always thought it's the duty of art to go against the status quo, to go against the established order of things. We had to sit down a bit and think, 'Well, why do we do this? Do we do it so we can get in the pages of Hello? It took us a bit of time to find out what our motives were for existing and making music, and to get back to doing that."

Cocker admits that This is Hardcore was a fifth album suffering from Difficult Second Album Syndrome. After all, its predecessor was a definitive Britpop moment, bringing its makers fame and financial security after a decade and a half of poverty and obscurity. Jarvis was a natural celebrity, with his droll delivery, quotable quotes, gawky frame and Oxfam chic. However, the honeymoon went somewhat sour when, at the Brits Awards in 1996, he famously protested against Michael Jackson's flatulent posturing by jumping on stage and pointing his arse in the direction of Jacko's Messiah-like form.

The tabloids, after initially going for Jarvis' throat, realised that they'd misjudged the mood of the masses and did an abrupt about-face, elevating him to the status of folk hero. (Fears that the Brits incident might come back to haunt Pulp when they recently shared a TFI Friday studio with Janet Jackson proved groundless. "It surprised me as well that she was on," Jarvis smiles. "But no, I can confirm that no contact was made.")

The tabloids, after initially going for Jarvis' throat, realised that they'd misjudged the mood of the masses and did an abrupt about-face, elevating him to the status of folk hero. (Fears that the Brits incident might come back to haunt Pulp when they recently shared a TFI Friday studio with Janet Jackson proved groundless. "It surprised me as well that she was on," Jarvis smiles. "But no, I can confirm that no contact was made.")

In addition to all this hoo-ha, there were upheavals in the Pulp camp. Guitarist/violinist Russell Senior, a key member of the band, tendered his resignation. Bassist Steve Mackay and drummer Nick Banks both fathered sons. Mark underwent a traumatic split with his girlfriend. Candida lost her brother to an Indian religious sect. It's no surprise then, that the opening verses on the new album are less a statement of intent than a memo from some convalescent home for bewildered rock stars: "This is the sound of someone losing the plot/Making out that they're okay when they're not/You're gonna like it/But not a lot" ('The Fear').

"I don't really like talking about these things in interviews because I've always hated the moany rock star who complains about their lot in life," Jarvis shrugs. "Although I wouldn't say it's like complaining about things, I think it's more that I don't really like change. I appal myself by being such a conservative character, I actually like things to go along in a certain routine. And I guess by the age of, like, 31 or whatever I was when Different Class came out, I was kind of used to being a failure, y'know? Well, not particularly a failure, but a certain degree of being known. And then suddenly it went a bit crazy and it was kind of hard to handle that change at first because I was quite set in me ways, happily plodding along. See, people were always asking us questions like, 'I bet you can handle it now because you're more mature', but what I've found, and I suppose it comes into the record a bit, is that this myth of adults knowing what the hell they're on about - it's a load of rubbish. In many ways they're worse than kids because at least kids react to things on an instinctive level and can't really be held responsible for getting things wrong. Adults should know better because they've got a bit of experience, but they just make the same mistakes over and over again and they've got no excuse for it."

The subject of adults and children is one that's been on Cocker's mind quite a bit over the last year. 'A Little Soul' off the new album sees him playing the role of a failed parent counseling his offspring ("You look like me/But please don't turn out like me") and Jarvis recently visited Australia to meet with his father for the first time in 24 years. Mac Cocker had gone to the papers expressing the wish to see his estranged son last year, but Jarvis refused The Sun's offer of money for pictures of the reunion.

"The song was written before I met me Dad," he explains. "It was written in the late part of last year, and I didn't meet me Dad until February this year. So, it was weird, as soon as I'd written the song I knew that I'd have to go and see him. Did it help me understand myself a bit more? I don't think I'll ever understand meself, it's a nice idea and thank you for suggesting it, but I haven't got a cat's chance in hell of that."

At the benefit show for avant garde composer La Monte Young at London's Barbican Centre last November, Jarvis dedicated 'Help The Aged' to his father. Here was the international playboy, sick of drugs, plaintively crooning "Give them hope and give them comfort/'Cos they're running out of time", without even the airbag of irony to soften the blow.

"That song came from being on tour and having to sleep in these bunks on a coach, which are kind of like the same dimensions as a coffin," Jarvis recalls. "So, getting in a coffin every night, probably quite pissed, makes you prone to maudlin thoughts. You can get slightly morbid. And over the last couple of years I have become aware of physical changes in me body and also in the way I think, and it made me quite aware of the fact that I was getting older. But the song's also a little bit cruel, it's just trying to get through that kind of sentimentality where you think of old people as people who are there to give you sweets on a Sunday, it's like they're a different species. One part of it came from this Scottish bloke talking about living in some bad housing projects in Glasgow in the '30s, and he said that for kicks what they used to do was get a hosepipe and run the gas through a pint of milk, and then drink the milk and it got you off your head. And that got me thinking, 'Everybody's kicking off about kids and their glue-sniffing, but people have always been doing it'. Everybody's thinking, 'Oh, a cute little pensioner', but they were a ragger. That set me mind off, thinking."

Cocker's refusal to distance himself from his subject matter has always given Pulp a humanitarian edge over the likes of Blur, whose Big Britpop Statement "The Great Escape" was ultimately a failed observation of '90s life, limited by its own glibness. No surprise then, that at the end of the new album, during 'The Day After The Revolution', the singer proclaims, "Irony is over".

"I've never been detached from the things that I write about," he insists. "I mean, I do see a lot of irony in the way that life works out, but I'm not detached from it and I wouldn't feel that I had the right to write about it unless I was doing the same thing as everybody else. I think there's a sense of people really sorting their lives out, they don't want to go into a new era married to the wrong person or doing the wrong things in their life, and there's no way you can approach that sort of setting-your-life-in-order with some kind of ironic detachment. It's gotta be for real. I guess that doing this record was me attempting to do that myself. I mean, I've never agreed with the view that we were ironic anyway, not in the way that it was usually used, which was that I had some kind of faintly amused, detached view of things."

"I've never been detached from the things that I write about," he insists. "I mean, I do see a lot of irony in the way that life works out, but I'm not detached from it and I wouldn't feel that I had the right to write about it unless I was doing the same thing as everybody else. I think there's a sense of people really sorting their lives out, they don't want to go into a new era married to the wrong person or doing the wrong things in their life, and there's no way you can approach that sort of setting-your-life-in-order with some kind of ironic detachment. It's gotta be for real. I guess that doing this record was me attempting to do that myself. I mean, I've never agreed with the view that we were ironic anyway, not in the way that it was usually used, which was that I had some kind of faintly amused, detached view of things."

It's not often that a music video does anything other than ruin the viewer's cherished preconception of what a song is about, but Pulp's clip for 'This Is Hardcore' is a notable exception in that it crystalises many of the underlying themes in the band's music. The clip, based around the premise of an unfinished Hollywood B-movie, suggests an almost tragic bete noir atmosphere, positing the camera as a clinical observer of human foibles, the artist as voyeur.

"The thing is, I think, because of the way our society is now, everybody's a voyeur," Cocker admits. "You get a lot of your ideas about the world from watching TV or films or listening to songs. I did anyway, maybe I got more than most because I just watched so much bloody television when I were younger, I dunno. So you're brought up with the idea of watching stuff, but then you find out that, although it gives the illusion of giving you information about things, all it's doing is showing you pictures of it, it doesn't actually explain what it's actually like."

So why portray such a grim, graphic song with such lush textures?

"Well, technicolour was like the apex of that thing in those big Hollywood films of the late '50s where everything was artificial," he explains. "You would never get colours like that in nature and, every time somebody got in a car it was done with rear projection. It's all completely stylised and I suppose a lot of the time our songs are about trying to get underneath that surface of what the things really are, but at the same time really liking that stuff."

The video clip concludes with a feathery homage to that "visionary lyricist of cinematic eroticism" Busby Berkeley, a pre- and post-war director whose camera moves have been compared to the thrust of the sexual act, and whose surreal choreography routines have suggested water-lily vaginas opening and closing (The Gang's All Here) and orgasmic sea anemones (Fashions Of 1934).

"I really love those things because they're so artificial and they could only exist for the camera," Jarvis enthuses. "And yet there's something very moving about those Busby Berkeley films. What I've kind of worked it out to is that he does these things where real people are making these fantastic kind of kaleidoscopic patterns in real time, all working together making this beautiful shape, so it seems very harmonious. Then he always gets a kind of close shot, where he goes along the chorus line and you see the individual girls faces, and they're not like fantastic beauties or anything, but they create this beautiful thing that can only ever exist for the camera. If you were there watching it happen, it wouldn't be the same thing. So that's why I was really glad that we managed to get that routine in at the end of the video."

The song itself suggests that Jarvis, the 'I Spy' of the last album, has, like one of Chandler or Marlowe's gumshoes, been wearied by too many years of witnessing human immorality. But instead of dispassionately taking snapshots and notes of an act that "men in stained raincoats pay for", he's also a willing participant. If that last album was about sex as revenge, this one seems to accept that revenge, especially when exacted through sex, is ultimately hollow.

"Hardcore pornography is the brick wall at the end of this kind of tunnel," Cocker decides. "If all the romance is stripped away, it becomes just a physical process, and you realise that... in some ways, you're constantly trying to strip this stuff away, all the artifice and the veils, and when you get to the end of it, to the actual thing, you want to put all the clothes back on it, because it's all a bit repulsive in a way. That's really what that song, and the record as a whole is trying to get at, that maybe you do have to keep a bit of distance from things. Hardcore porn has a brutalising effect. I mean, it's like life itself. If you get down to the basics of life - eating, shitting, fucking, whatever - if you think of it like that, it's pretty brutal. You have to add a spiritual or human dimension to make it something more. There's an obsession in our society of seeing stuff - I mean, I was away when the last part of that Human Body programme was on, when they were going to show the bloke dying. I was curious like anybody else about seeing that, but there was part of me that thought, 'You know, maybe this is one of these things that you shouldn't show'. This thing that because now you can show it, that you should, or that it's stupid to keep these illusions - maybe what people are realising now is that you get to this nitty-gritty, and it's quite a cold, uninviting place."

"Hardcore pornography is the brick wall at the end of this kind of tunnel," Cocker decides. "If all the romance is stripped away, it becomes just a physical process, and you realise that... in some ways, you're constantly trying to strip this stuff away, all the artifice and the veils, and when you get to the end of it, to the actual thing, you want to put all the clothes back on it, because it's all a bit repulsive in a way. That's really what that song, and the record as a whole is trying to get at, that maybe you do have to keep a bit of distance from things. Hardcore porn has a brutalising effect. I mean, it's like life itself. If you get down to the basics of life - eating, shitting, fucking, whatever - if you think of it like that, it's pretty brutal. You have to add a spiritual or human dimension to make it something more. There's an obsession in our society of seeing stuff - I mean, I was away when the last part of that Human Body programme was on, when they were going to show the bloke dying. I was curious like anybody else about seeing that, but there was part of me that thought, 'You know, maybe this is one of these things that you shouldn't show'. This thing that because now you can show it, that you should, or that it's stupid to keep these illusions - maybe what people are realising now is that you get to this nitty-gritty, and it's quite a cold, uninviting place."

This Is Hardcore might be seen as the mother of all sexual hangovers, the moaning after the night before. Certainly, Jarvis fell foul of the odd tabloid fuck-and-tell episode. Did women queue up to be blessed by the Cocker cucumber?

"They did, and I did take advantage of it, yeah," he admits. "And I suppose I paid the price for it. If you think of fucking someone in the same way as you think about having a cigarette or a drink, that's not right. 'Course, then the thing is, I'm in a band and we sell records, and in a way I'm a commodity, and if you start thinking that way yourself, maybe you're gonna run the risk that you get consumed and chucked away. The women in these porn films get used up at a rate of knots. It's like seeing people as consumer products, and I suppose maybe it is a symptom of the fact that now, you buy something, you use it and you chuck it away, and to start seeing human beings in that way is wrong, and it does happen."

This disillusion with mechanical sex is highlighted in the line, "What exactly do you do for an encore?" - the point when the heat of the moment evaporates, and you're left with dick in hand, covered in baby oil or hazelnut yoghurt or human faeces, feeling empty, spent, and stupid. "Well, yeah, it's the feeling that you've done it all, or exhausted every variation," Jarvis admits. "And I'm not just talking about a sexual thing here. Then you say, 'Well, what do you do for an encore?' Maybe that was a question that I was asking meself a lot whilst we were actually making the record. But it answered itself really, because we made another album."

"Eh, yeah, it's always a fine line, and I hope I'm not too much of an arsehole," he concedes. "Like for instance, I went off and did this Channel 4 film (Cocker co-directed a series about "outsider artists" that will air next year) immediately after the album came out. I know Island were completely horrified by this, even though I told them about it, four months in advance. But when the reality of it hit them, they were very done in. But for me, I knew that I had to it at that time, because it was such an involved and slightly painful process making the record, and I knew it was very important for me to go off and do something else, on which the band had no bearing at all. But then I was meeting these people in these weird and wonderful places out in the middle of nowhere: they have no contact with the outside world so they don't know who you are, you have to relate to them on a completely normal human level, there's no PR to go in and smooth the way for you, all this kind of shit. Going out and seeing people who create these things just because they want to, and they can't even define why they do it most of the time, that was important as well. I could see how it looks bad from the outside if your album's taken ages and then you fuck off for two months when it comes out, but to me it made perfect sense."

"Eh, yeah, it's always a fine line, and I hope I'm not too much of an arsehole," he concedes. "Like for instance, I went off and did this Channel 4 film (Cocker co-directed a series about "outsider artists" that will air next year) immediately after the album came out. I know Island were completely horrified by this, even though I told them about it, four months in advance. But when the reality of it hit them, they were very done in. But for me, I knew that I had to it at that time, because it was such an involved and slightly painful process making the record, and I knew it was very important for me to go off and do something else, on which the band had no bearing at all. But then I was meeting these people in these weird and wonderful places out in the middle of nowhere: they have no contact with the outside world so they don't know who you are, you have to relate to them on a completely normal human level, there's no PR to go in and smooth the way for you, all this kind of shit. Going out and seeing people who create these things just because they want to, and they can't even define why they do it most of the time, that was important as well. I could see how it looks bad from the outside if your album's taken ages and then you fuck off for two months when it comes out, but to me it made perfect sense." Sex, Lies & Videotape

Sex, Lies & Videotape The tabloids, after initially going for Jarvis' throat, realised that they'd misjudged the mood of the masses and did an abrupt about-face, elevating him to the status of folk hero. (Fears that the Brits incident might come back to haunt Pulp when they recently shared a TFI Friday studio with Janet Jackson proved groundless. "It surprised me as well that she was on," Jarvis smiles. "But no, I can confirm that no contact was made.")

The tabloids, after initially going for Jarvis' throat, realised that they'd misjudged the mood of the masses and did an abrupt about-face, elevating him to the status of folk hero. (Fears that the Brits incident might come back to haunt Pulp when they recently shared a TFI Friday studio with Janet Jackson proved groundless. "It surprised me as well that she was on," Jarvis smiles. "But no, I can confirm that no contact was made.") "I've never been detached from the things that I write about," he insists. "I mean, I do see a lot of irony in the way that life works out, but I'm not detached from it and I wouldn't feel that I had the right to write about it unless I was doing the same thing as everybody else. I think there's a sense of people really sorting their lives out, they don't want to go into a new era married to the wrong person or doing the wrong things in their life, and there's no way you can approach that sort of setting-your-life-in-order with some kind of ironic detachment. It's gotta be for real. I guess that doing this record was me attempting to do that myself. I mean, I've never agreed with the view that we were ironic anyway, not in the way that it was usually used, which was that I had some kind of faintly amused, detached view of things."

"I've never been detached from the things that I write about," he insists. "I mean, I do see a lot of irony in the way that life works out, but I'm not detached from it and I wouldn't feel that I had the right to write about it unless I was doing the same thing as everybody else. I think there's a sense of people really sorting their lives out, they don't want to go into a new era married to the wrong person or doing the wrong things in their life, and there's no way you can approach that sort of setting-your-life-in-order with some kind of ironic detachment. It's gotta be for real. I guess that doing this record was me attempting to do that myself. I mean, I've never agreed with the view that we were ironic anyway, not in the way that it was usually used, which was that I had some kind of faintly amused, detached view of things." "Hardcore pornography is the brick wall at the end of this kind of tunnel," Cocker decides. "If all the romance is stripped away, it becomes just a physical process, and you realise that... in some ways, you're constantly trying to strip this stuff away, all the artifice and the veils, and when you get to the end of it, to the actual thing, you want to put all the clothes back on it, because it's all a bit repulsive in a way. That's really what that song, and the record as a whole is trying to get at, that maybe you do have to keep a bit of distance from things. Hardcore porn has a brutalising effect. I mean, it's like life itself. If you get down to the basics of life - eating, shitting, fucking, whatever - if you think of it like that, it's pretty brutal. You have to add a spiritual or human dimension to make it something more. There's an obsession in our society of seeing stuff - I mean, I was away when the last part of that Human Body programme was on, when they were going to show the bloke dying. I was curious like anybody else about seeing that, but there was part of me that thought, 'You know, maybe this is one of these things that you shouldn't show'. This thing that because now you can show it, that you should, or that it's stupid to keep these illusions - maybe what people are realising now is that you get to this nitty-gritty, and it's quite a cold, uninviting place."

"Hardcore pornography is the brick wall at the end of this kind of tunnel," Cocker decides. "If all the romance is stripped away, it becomes just a physical process, and you realise that... in some ways, you're constantly trying to strip this stuff away, all the artifice and the veils, and when you get to the end of it, to the actual thing, you want to put all the clothes back on it, because it's all a bit repulsive in a way. That's really what that song, and the record as a whole is trying to get at, that maybe you do have to keep a bit of distance from things. Hardcore porn has a brutalising effect. I mean, it's like life itself. If you get down to the basics of life - eating, shitting, fucking, whatever - if you think of it like that, it's pretty brutal. You have to add a spiritual or human dimension to make it something more. There's an obsession in our society of seeing stuff - I mean, I was away when the last part of that Human Body programme was on, when they were going to show the bloke dying. I was curious like anybody else about seeing that, but there was part of me that thought, 'You know, maybe this is one of these things that you shouldn't show'. This thing that because now you can show it, that you should, or that it's stupid to keep these illusions - maybe what people are realising now is that you get to this nitty-gritty, and it's quite a cold, uninviting place."