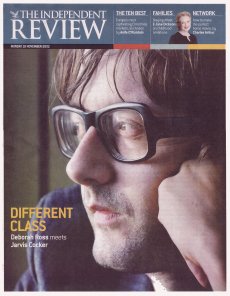

The People's Pop Star

The People's Pop StarJarvis Cocker's melancholic songs about English life have charmed us. And, with his NHS specs and pallid demeanour, he's become something of a national treasure. But now that he has a new home (in Paris, no less), and a baby on the way, why is he still worrying about sewing buttons back on his jackets?

I meet Jarvis Cocker at St Pancras station. He's off to Sheffield, for his mother's 60th birthday party - "down her local" - and the deal is that I can talk to him on the way up and then, at Sheffield, I can cross platforms and travel directly back to London. Oh, such glamour! Anyway, the station is crowded but Jarvis is, of course, blissfully easy to spot. He is ghostly white, almost translucent, extremely tall, and very, very, very, geekily thin. He may, now I think about it, be the absolute opposite of butch. Not so much caveman, more concave man? And, yes, he wears those funny Larkin specs. He has tried contact lenses, but a rather slapdash attitude towards any kind of cleansing regime led to infection after infection and then, one night, he stored them in a couple of spice jar tops, but one of the spices was chilli powder, and when he put the lens in the next day his eye practically exploded. He ended up in Moorfields Eye Hospital "where it was suggested to me that I go back to glasses".

I don't think he is overly preoccupied by hygiene. His wodge of dark hair is a bit greasy. The fingernails at the end of his etiolated, spectral fingers are a bit grubby. Even if I wasn't Jewish, I think he'd bring out the Jewish mother in me. Oh, how I'd love to feed him up. And hose him down.

However, he is, alas, already spoken for. Indeed, he is travelling today with his pregnant, Parisian wife, Camille, a fashion stylist. She seems perfectly clean, and is wearing tres chic lime-green, platform boots. "Nice boots," I say admiringly. "Hmmpph," she goes. The photographer later tells me not to mind. She's French, he says, and French women can be very sulky. I don't know what it is with her. Hormones? Meeting me? Perhaps, if I had to meet me, I'd go "Hmmpph" too. In fact, I bet I would. I was minded to give her tips on the feeding and hosing front, but I don't think I'll bother now.

Whatever, the baby is due on 13 April which, says Jarvis, "is nine months to the day from our wedding. I don't believe in sex before marriage but once you are, YES!" I say I've thought of a good name for this child of his. Snook. That way, when his/her name is read out from the register at school, it'll go: "Cocker, Snook." You could also have Doodle-doo, Leg, Hoop... He's not much taken with this (brilliant) idea. He says: you try growing up with an eccentric name. He adds: you try growing up in Sheffield, in the Sixties, with an eccentric name. Being "Jarvis" wasn't much fun, you know. "I hated it. When I first went to Cub Scout camp I told everyone my name was John. For a whole week I pretended to be John, and lived in mortal fear of being found out."

This, I guess, is one of the defining things about Jarvis Cocker: his longing to be the same as everyone else, but never quite managing it. Always the misfit, the weed, the marginalised one, the geeky kid who was rubbish at sport, the one whose mum sent him to school in shorts that were too short ("my jumper always covered them... it looked like I was wearing a jumper dress"), the awkward adolescent who never got the girl, the freaky outsider looking in. It's what has informed so many of his wonderful songs.

On the other hand, he later says something that might be just as telling. He says that when he was at school, he remembers a lesson on pie charts, and all the children had to say what time they got up in the morning, so he said 7am, which was actually an outrageous and absurdly obvious lie ("I was always late for school") but he knew if he said 7am, it would be earlier than any of his classmates, "and I wanted a segment of the pie chart all to myself". So that's the other thing. He wants to be the same, but doesn't wish to lose his difference. One of the most engaging things about Jarvis Cocker is that he can't be bothered to be conveniently straightforward.

We get on to the train. As it turns out, Jarvis and Camille are in one carriage, the photographer and I in another. Jarvis, it is understood, will move to speak to us at some point. We all travel standard class. (Oh, such glamour!) Jarvis is certainly one of the Common People, and is famously Yorkshire-frugal. He uses pay-as-you-go phone vouchers. He's not as bad as an uncle of his, though, who, he says, used to go through the bins to see what Jarvis's aunt had thrown away, and if he found a loaf of bread he'd storm back into the kitchen with it, shouting: "There's nowt wrong with it, once you've cut the mould out."

At one point, I see Jarvis making his way through the carriage towards the photographer and I, but it's a false alarm. "Just getting a coffee and sarnie," he says. From behind, he appears to have no botty whatsoever. In fact, if I hadn't seen it that time at the Brit Awards - you know, when he wiggled it at Michael Jackson, who was humbly affecting to be The Messiah at the time - I'd swear that he didn't have one, that he was curiously botty-less, was from planet No Botty.

I later ask him what was going through his mind just before he got on stage. "A lot of alcohol," he says. "And some drugs." I think he rather regrets that incident now. It did transform him into a tabloid caricature for a while. But, on the other hand, someone had to do something, he insists. "I don't think it was that pathetic. All the Brit people were so full of themselves and excited because Michael Jackson was there. They let him do anything he wanted to do because they were just so made up to have him. But it was distasteful; really shit. But you can do that crap when you're famous. You can do anything when you're famous. That's why famous people are so dumb."

Sadly, he has no plans for any further stage-storming incidents which is a shame, as I'd quite like him to have a shot at S Club Juniors and, if not slit their throats - they're only children, for god's sake - at least give them several Chinese burns and send them directly to bed without supper.

He joins us properly, eventually. He is as ethereally vague as he is ghostly. He looks out of the window a lot. I think we only make eye contact when I ask him how shortsighted he is and he removes the funny Larkin specs and draws his face close to mine. "Hey," he says. "You look like Cybill Shepherd." I guess that he is extremely shortsighted. I ask what he's got for his mum's birthday. "Some chocs and a kind of notepad in a silver case."

He then says he's in a bit of a grumpy mood - he's had a horribly frustrating morning. Oh? He says he directed a telly advert to promote Pulp's latest CD, a greatest hits compilation, but the record company, Island, now says that it doesn't like the ad, that it won't shift records, and so it won't release it. Jarvis isn't sure about its market-research methods. "I think they go to HMV on Oxford Street and ask 30 young mums what they've just bought." He says the ad, which he describes as a piss-take of "the smarmy Britta one with its tepid innuendo", isn't "the greatest cinematic effort ever, but I thought it was kinda funny". The trouble with the record company, he concludes, is that "they are just bastards basically. It just reminds me why we finished our relationship with them."

Hang on, I interrupt. You've finished your relationship with them? "They offered us another contract but because of the way things have been going - they took six months to release our last album - we decided not to do it. We thought it would be cowardly to do it." So Pulp have no record deal now? Isn't that scary? "No. If we want to do another record, all we have to do is write some decent songs, play 'em to someone, and if they like 'em they'll do a record." I don't know if this means that Pulp are finished or not. I don't even know if he knows if Pulp are finished or not. He says they're due to headline a festival in Sheffield on 14 December, "and after that we're all going to take a year off". (NB: Jarvis's PR has just informed me that Island has had a change of mind, and will be using the TV ad. Hurrah! I hate those smarmy Britta people. No Chinese burns and bed without supper for them. Slit their throats, I say!)

I ask if, deal or no deal, he'll carry on songwriting nevertheless. Is he compelled to do it in the way that, say, some writers are compelled to write? He says that's not him at all. "I'm lazy. I think of bits and bobs but I won't make them into a song until my life depends on it." The big question now, I think, is whether Jarvis has any more songs left in him. I ask if he worries about having said - musically and lyrically - everything he ever had to say. He says he does, yes. He is 39 now, "and the things that you think about in later life are generally unpalatable and are really not worth writing songs about". Like? "The other day I put an old jacket on, felt in the pocket, and found a button, which had obviously come off at some point and which I'd put in the pocket thinking I would sew it back on one day, even though there wasn't a cat in hell's chance that I ever would. And then I thought: when I die, people are going to find all these jackets with buttons in the pocket that I'd never sewn on and... it's not feel- good stuff, is it? It's not the sort of stuff you want to lumber people with."

I say it's hardly rock'n'roll, but it's a touching observation. Melancholic, but also universally true. I think we all store things (I'm always buying seed packets, although I've yet to plant a seed in our garden) for the day when we'll suddenly turn into the sort of person we hope we might become - a seed-planter, a button-sewer - even though, in our hearts, we know we never will. I think there is a subtle poetry in this, but then I think Jarvis is maybe quite subtly poetic generally. I like it when, later, he confesses to a pretty bad carrier-bag habit - "me house is all cluttered up with them" - but can't find it within himself to fully embrace the flimsy ones you get from the newsagent. "As thin as angels wings," he sighs. His favourite are the Duty Free ones that come with the rigid plastic handles that pop together. "You can get a lot in one of those," he says happily.

Jarvis was born and brought up in Sheffield, mostly by his mother, Christine, a one-time art student who ended up emptying pub fruit-machines to support Jarvis and his younger sister, Saskia. Indeed, their father - Mack Cocker, an occasional jazz musician and actor - left the family home when Jarvis was seven, never to be seen again until around five years ago, when a tabloid - inevitably - tracked him down in Australia. Jarvis has seen him since, and says he feels no anger: "I think he went through certain things that let him close certain parts of his life off."

He then says that maybe he's more bothered by the dad thing than he'll admit "as I did write a song about it, 'Little Soul', which is about a father abandoning a kid, then the kid bumping into him in the pub and the dad being too hammered to talk, the dad just saying 'go away'." He adds that he's absolutely terrified of his own impending fatherhood because "I've nothing to base my father act on. I'm going to have to make it all up as I go along."

Jarvis first formed Pulp at 15, mostly because he thought that, if he had a band, he could be in a gang and get girls. Pulp took 17 years to make it, and didn't have any success at all until "Common People" in 1995. At one point, I ask him to describe the grimmest period of his life, thinking he'll say something about the non-successful years, when he lived in a damp squat and had to eat mice or whatever. But he says it was just after Pulp hit the big time, "and I was getting panic attacks and getting drunk and doing drugs with a lot of other people doing drugs and having a horrible time but no one had the courage to stand up and say: 'I'm having a terrible time. Let's stop doing drugs. Let's go ten-pin bowling.' It was just horrible; I should have been at my happiest, but I was expecting fame to be something it wasn't. I thought it would cure my social awkwardness, that I'd slide into social situations with ease, that I wouldn't have to bother chatting anyone up. I could just say: 'Hey, babe, it's me.'"

And? "The dream doesn't do what it says on the can. It actually made the social thing worse. And it took away my invisibility. A lot of our songs are observational songs, and it took my perspective away." He says he and Camille are going to move to Paris. They've found a flat and everything, and he's looking forward to it. "It'll be nice to have my anonymity again." I think that what he's trying to say is once an outsider, you can never be an insider, no matter how many drugs you take. And it can take a mini-breakdown to tell you that.

Anyway, we're nearing Sheffield now, so I walk him back to his own seat. He gives me a tip on the way. Swedish supermarkets, he says, do really nice carrier bags "with little reindeers on". I apologise to Camille for keeping him so long. "Hmmpph," she goes. It's the hormones, I bet. I was minded to also suggest Too, Leekie and Spaniel, but don't think I'll bother now.