The People's Pop Star

The People's Pop StarThree years after moving to Paris, Jarvis Cocker is back with an acclaimed new solo album. Here, he talks to Hermione Eyre about marriage, music - and the truth about Father Christmas.

Jarvis lives half-way up a sumptuous gilt rococo staircase in the ninth arrondissement of Paris. His bell says "Cocker-Bidault-Waddington" but he hasn't gone triple-barrelled on us - mixing in his wife's surname is just for the doorbell, not for life. Their two-year-old son is plain "Albert Cocker" (a name that makes the boy sound like a trade union leader, Jarvis thinks). I'm calling on him at his home, then we will drive through town to a tea-room: it's going to be a grand day out in Paris with Jarvis.

He calls out a melancholy Northern "hullo". He is loitering in the doorway, the man that freed a thousand geeks, in a new jumper ("not second-hand, this one, actually"), tartan shirt, and jeans that go on for ever. How elegant, how epicene his movements are. He sits me down and disappears to make coffee, so I get a good squiz at his front room, which is done out in that effortless bohemian chic that takes so much effort: extravagant Sixties lamps, huge paper flowers, tasteful rustic Christmas decorations. The hall is painted Angel Delight pink, which off-sets the Pop Art prints. His wife, Camille, is a top fashion stylist, just in case you didn't hate her already.

"I let her rule the roost here," he says, coming in carrying a little tea tray, looking very domesticated. "I never used to think having a nice home was important. When I was a teenager I thought if I ever got enough money I would just live in a hotel. So this is quite a recent development. Cheers, or whatever it is you say with coffee."

It's here that he has been holed up for the past three years, starting a family and working on his new album, Jarvis - his first solo work. It has got pretty much universal rave reviews, which he's pleased about - "I wish I didn't care, but I do" - even if some of them are slightly baffling. "They said I was what? A Yorkshire Elvis? I ain't that fat. And he's got one of the great voices, and I certainly haven't."

Always down on himself, our Jarvis. He really is, though. Throughout the interview, he says things like, "Ugh, it's just me droning on, 'I think this, I think that...'"; when we don't have quite enough money to leave a good tip in the restaurant he makes a brief pantomime of guilt - "I feel bad. I am bad!" He would make a good Catholic, if he weren't an atheist. "Or a Humanist. I guess that's closest to what I believe in, really." Christmas would make more sense to him if, instead of not going to church he could go to "a big secular building that smelled nice".

He wrote the album in the apartment, and also in a little room down the road (the bunker-like space he's pictured in on the album sleeve). "I hired it as a place I could be loud and noisy in. It was the first time I'd been loud in about 18 months," he says, adding matter-of-factly, "so I spent about 20 minutes just screaming."

Primal screaming? "Something like that. It was quite, er, therapeutic. I need to do that because as you've probably gathered by now, even though you only met me half an hour ago, my general mode of expression is..." (pulls a zombie face). "Not much, er, modulation in me tone of voice." Is the screaming thing a life-long habit? "I used to do it a lot. When Pulp first started I used to go into a garage at the side of me mam's house and make a lot of noise. That was embarrassing sometimes because there was a hairdresser's and a sweet shop in the yard behind and they'd say, 'Heard you yesterday'.

"I don't like the idea of being overheard while you're doing something. Obviously when you're performing on stage you want people to listen; I mean you're pleased if they don't walk out. But if I walk into a room and one of my records, or a Pulp record, is on I find that embarrassing."

The real you feels self-conscious in front of the recorded you? I volunteer. There's a long pause. He looks out of the window into the rainy Paris sky. Maybe it was a pretentious question. Cocker can't stand pretension, as Michael Jackson well remembers. Perhaps he is going to get up and do a fart routine in my face.

But he says dreamily, "D'you know that film, The Man Who Haunted Himself? It's a cheesy film, but one of my favourites." In it, Roger Moore has a near-fatal car crash, develops two heart beats, and starts being haunted by a louder, brasher version of himself. "What really got me," says Jarvis, "is the way his alter-ego is much more popular than him."

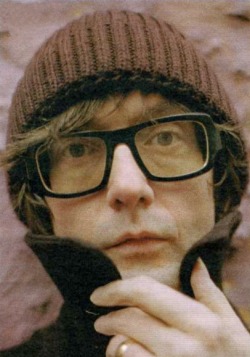

He eyes me cautiously through his Cutler and Gross specs, composed, watchful, haunted. "Jarvis" the showman, the bold, famous alter-ego is one thing, but the other Jarvis I'm sat here with is quite another, the private one who gets embarrassed, who worries he's becoming a grumpy old man, who tries, all the time, to be a Good Person: "You might not be the World's Greatest Dad Ever or the Best Husband, but you do your best and you stick at it."

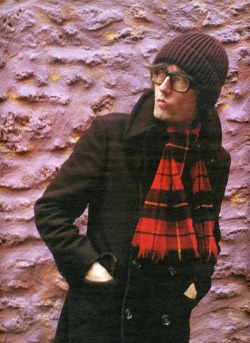

But now we have to get ready to drive off to a photo shoot. He dons an overcoat, woolly scarf and bobble hat. He looks like an adorable, sexy Where's Wally. "May I run to the loo?" I ask. "You can walk if you like," he says, sounding for all the world like Mrs Merton. Jarvis's car looks like it came from a Sue Ryder charity shop. It is a 1986 Chrysler Town and Country with imitation wood panelling across the chassis and a faux crystal steering wheel. As we drive, he flicks its broken indicator.

Born in 1963, he grew up in Sheffield with his mother Christine, now a Tory councillor ("But we won't talk about THAT!") and younger sister Saskia. His father, Mack Cocker, an actor and DJ, walked out on them when he was seven, and emigrated to Australia where he claimed to be Joe Cocker's brother. Perhaps he now claims to be Jarvis Cocker's brother. They aren't in contact, and met only once when he and Saskia flew over there, but Jarvis has always maintained he has forgiven his father. "I don't feel any bitterness towards him at all. I feel sorry for him." An awkward, spindly boy, Jarvis was bullied a bit. "My name didn't help. In Sheffield, in secondary school, if you were f-hard they'd call you "Cock o' the Year". When I arrived I got, "Are you Cock o' the Year then, do you wanna fight?" "No thanks." "Are you Cock o' the Crap Fighters, then? Cock o' the Poofs?"

Jarvis's hands, long and spectral like Lytton Strachey's, flutter over the steering wheel. "I was always very nervous physically when I was younger," he tells me, in a traffic jam. "I never went rollerskating or went diving from the top board - couldn't ride a bike till I was in me twenties." Then, in 1985, he fell out of a window while trying to be Spiderman to impress a girl. "I broke a wrist and ankle and pelvis, but felt I'd survived. I actually became a bit more fearless." After "the wheelchair months", Jarvis applied for art college - Saint Martins, where as we know, he met a girl who came from Greece and had a thirst for knowledge.

But there were long years yet before he wrote those words to Pulp's greatest hit. Pulp, the band he had founded when bored in an economics lesson aged 15, made four albums together, each a little more warmly received, until in 1995 they released Different Class, and, as they say, exploded. Jarvis realised this when he played "Common People" at Glastonbury and 100,000 people sang along with him, word perfect. "It makes you feel you haven't wasted the last 15 years of your life ... Makes you feel you weren't mentally ill all that time," he later said. The album went triple platinum and won the Mercury Prize.

Jarvis is a calm, considerate driver. He is not selling Paris very well today, though. The Place Vendôme: "nice". The famous Christmas lights: "pretty nice". The Paris Opera, magnificent and floodlit: "quite a building". Not one to gush, Jarvis. "There's meant to be a secret lake underneath it. Apparently a caretaker who works there was sacked for introducing trout to it, making it into his own trout farm. I quite liked that story."

"Pour moi, un thé Verveine, s'il vous plait." Jarvis still sounds like Jarvis, even when he's speaking French. The flat south Yorkshire vowels hold true. The effort of ordering in the language done, he relaxes those telescopic limbs. "Shall we have a fag then?" We're in his favourite pâtisserie, which he likes because he can pop next door afterwards to the English bookshop. He doesn't seem very at home in Paris. "If I go to dinner parties I don't understand what anyone's saying." Here, he is also thwarted in one of his great pleasures in life: eavesdropping. "I just like wandering round, seeing what people are up to. Not in a sinister way, I hope."

He has a fine sensibility for the sinister. "Without those slightly dodgy impulses life would be very dull. The conventional view of what heaven would be like sounds so dull you'd probably want to kill yourself." His new album is witty, but dark - how a David Shrigley drawing might sound if it sang, particularly the track "I Will Kill Again". The phrase comes from the tape created by the Yorkshire Ripper hoaxer. "He was finally arrested for perverting the course of justice - quite recently, after I finished the song. Also, and this is horribly trivial, but that was our catchphrase round the house for a while, sort of, 'Are you going out tonight?' 'Yes, I will kill again'." Another track, "From Auschwitz to Ipswich", a song about "the mundanity of evil", has now acquired a chilling prescience. He chose Ipswich simply because it was an innocuous place and it half-rhymed.

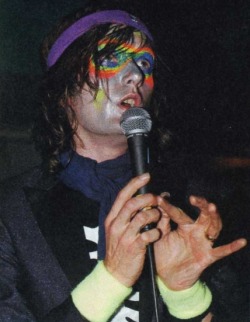

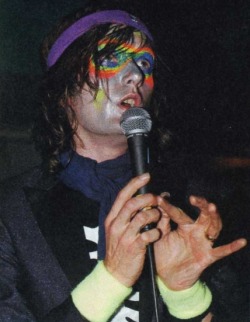

The waitress comes back carrying a book, The Art of Blasphemy, a present sent over for him from an anonymous fan in the café. "I didn't set this up," he says. "Honest." Does he like practical jokes? "I do like to wind people up." And what about that alter-ego, the rancid, phlegmy band leader who looked a bit like Jarvis in make-up, sounded a bit like Jarvis through a voice distorter, but insisted he was Darren Spooner? "That was more like a Jekyll and Hyde thing, so I could give him all my negative attributes. At that time I was getting married and me wife was pregnant and I thought I could take all this shit and put it into a ball and call it Darren and that would make me a nicer person."

Back in Sheffield for Christmas, will he pretend to be Santa Claus for Otto (his stepson) and Albert? "I might put a hat on a stick and wave it outside the window - 'He's coming! He's coming!' That would get them off to bed. I've had the whole debate with myself about whether a parent should lie to their kid about Santa but I've ended up doing it anyway."

His wife's on his mobile. He has to go. "Success can really turn somebody into ... a monster," he says. "What a lot of people seem to want to do with success is buy a stately home and create their own universe, detach themselves and control every situation that they come into, you know? But the reason I wanted to be in it when I first started was really due to social ineptitude, I thought it would help me mix with people, act as an introduction so you never have that horrible thing of not knowing whether to talk to somebody or whatever. All I really wanted was for it to make me able to do normal things."

The child minder needs letting in. Santa hats need to be put on sticks. Records about the essential darkness of humanity need to be written. Jarvis has left the building.

Thanks to Catherine for submitting this article.