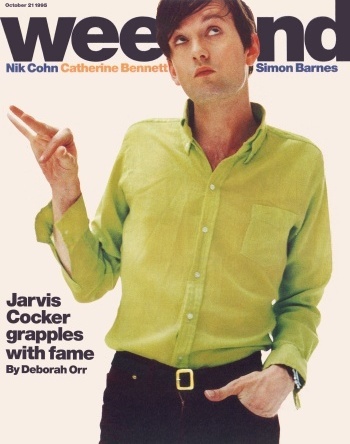

Mea Pulpa

Mea PulpaHe might have been the Voice of the Eighties but he was left idling on the launch-pad. Now Jarvis Cocker, sleeping prince and iconoclast, has woken up to his fabulous inheritance.

The evening does not start well. Seven strides into the concert hall, and there's a body to step round. She's tiny, adolescent, sprawled on a perkily patterned carpet that's covered in the crunchy debris of broken plastic glasses. She looks far too young to be in a licensed venue. She looks like she ought to have her thumb in her mouth.

A couple of security guys are huddled over her. They seem dreamy and confused. Their hands hover uncertainly around her body, as if by massaging the air around her they can waft her gently back to consciousness. She doesn't appear to have any friends with her. What can it be? Drink? Drugs? Sheer excitement? Or is it just way past this child's bedtime?

One thing is for sure. She won't be seeing Pulp this evening. The etiolated, elegant forefinger of pop's rising megastar won't be pointing in her direction. Jarvis Branson Cocker won't be speaking to her tonight like she's the only girl in the room. She's leaving on a stretcher. Ah, the heady, glamorous world of popular music, where hysteria is courted, novelty is worshipped, talent is squandered, and too much can never be enough. Fabulous. It's wasted on teenagers, it really is.

The performance doesn't start well either. When Jarvis Cocker trips out onto the University of East Anglia's student-union stage, he looks dazed and distant, as if he'd expected the door he'd just stepped through to lead to a broom cupboard, not to an excited crowd of cheering, manic people. The set begins - great musicians, fabulous tunes, nice light show - it's all okay. Except that Cocker isn't making contact with the audience, not like he usually does. He's halfway through his first major tour. And the man who boasts that as a pop star you're on call 24 hours a day is already going through the motions.

After a couple more songs he feels it necessary to explain the situation to his paying guests. He doesn't really feel like doing this tonight, he admits. He's had a couple of late nights, and he's really tired out. The audience responds with a weird collective flinch. It's terrible, being in a band, adds Cocker, and smiles at his own absurdity. From here on in, things get better. Cocker loosens up, becomes playful, gets his elaborate persona under control, unleashes his humour and his wit. Everyone is enchanted, everyone is singing along, everyone is happy. When the show comes to an end, its star thanks us all charmingly for being so great and getting him out of his momentary attack of the bad attitudes. We, the audience, have won Jarvis Cocker over. We are tickled pink about this. We are glad that he felt he could confide in us. We have shared his problem, and we have halved it. We feel, pretty much, that all is well that ends well. But for Cocker, the evening is not yet over. There are further horrors to come. Little horrors.

The backstage party is not looking promising. We are in a horrible room. It's big and empty and feels like it's never used. It has a mean little vinyl bench running round it, and the half dozen tables are bolted down. There is no music. The striplights are so bright that you might as well be sitting in a fridge. Except that there is nothing to eat and nothing to drink. It is like one of those youth clubs that make street corners so attractive to 13-year-olds. Nick Banks, Pulp's sunny drummer, wanders through to salvage the situation. In no time at all, like magic, one crate of Stella Artois, a bagful of candles, a tinny radio-cassette player and The Best Of The BBC's Theme Tunes appears. The room is transformed. Now it's like the shed your parents let you play in before you were old enough to go to the youth club. Indeed, waves of children of around that vintage are suddenly, inexplicably, herded into the room. In a trice they appear to have become attached to the lower half of Jarvis Cocker's lanky body. His little botty, snug in Crimpleney flares, dances among their heads. They are voracious, pitiless. There is nothing they don't want a signature on. Their demands take up hours. Cocker bats on gamely, but he is really knackered. At times he looks almost tearful - though this is probably contact lens trouble. No one shows more than a cursory interest in the group. (Who are, for the record, Russell Senior, Steve Mackey, Candida Doyle, Nick Banks and Mark Webber.)

It's impossible to speak to Cocker for more that a few moments. He'll break away occasionally and try out another bit of the room. In no time, the kiddies attach themselves again. Adults don't want to be near him because it means being near them. God knows where they have come from. God knows why they are out so late. Go knows why a grown man is putting up with them. God knows why anyone would want fame this much. The answer is simple. He's making up for lost time. Jarvis Cocker is the man who mislaid a decade. He's 32 years old and only just beginning to realise that being a pop star may at times not be so different from being a Blue Peter presenter. He first got it clear in his mind that the former, not the latter, was the job for him when he was around 14. That, it may seem, would have been the appropriate time to go ahead and do it, the time when his fans would also have been his peers, and could have grown up with him. However, going ahead and doing it has taken 18 years, and while Cocker himself points out that he's old enough to be the father of some of his public - well, better late then never. It would be churlish to disagree, for Cocker has spent those 18 years honing himself for the job he never stopped hoping he'd eventually get, When fame called, he was more than ready.

The man is virtually a pop paradigm. Describing Cocker has become something of a preoccupation for the music press, but there's really not much point in trying to best Select feature writer, Adam Higginbotham: "The stage presence of peak-period Alvin Stardust and the withering deadpan wit of Alan Bennett in the body of Kenneth Williams" There's one thing to add. Jarvis Cocker is a lyricist of tremendous power, cleverness and subtlety and his songs are every bit as complex, idiosyncratic and beguiling as the man himself. So, better late than never indeed.

We're waiting for the telly to warm up in another grotty room. It's a Sony Trinitron, and must have been one of the first colour TVs ever manufactured. Several telly warming up jokes float around the room, which is full of music PRs. Obviously, the staff of Savage & Best - which is more or less a Milk Marketing Board for what we are pleased to call Britpop - are very indulgent of this television. It's typical of the pop business that, despite the huge amounts of money sloshing around, the young people who do the graft are encouraged - and want - to work in atmospheres of happy amateurism. It makes indie types like Jarvis Cocker feel comfy and at home, the better to extract profits from them. We're here to watch the master tape of one of the videos for Pulp's double A side single, Mis-Shapes and Sorted For E's & Wizz. The later has attracted tabloid attention and a call for a ban, but the former is the song that contains Cocker's statement of intent. You can't see much on the tiny screen, but everyone laughs at the right places as Cocker bumbles around a seventies disco, being bullied and ridiculed by all, and dreaming of mowing them down with a machine gun. Cocker, viewing the video for the first time, pronounces himself happy with it, although he says he's been pretty worried about the whole thing. "I was very scared about doing that stuff". Acting. It's a bit dodgy for pop singers. You wouldn't want to end up like Sting or something, would you?" God, no.

The song is a triumphalist stomp charting the rise of "mis-shapes, mistakes, misfits" - their years in the wilderness, and their eventual triumph: "We want your homes, we want your lives, we want the things you don't allow us. We won't use guns, we won't use knives, we'll use the things that we've got more of. That's our minds." Needless to say, there are parallels with Mr Cocker's own life here. And although the all-embracing sweep of the song is somewhat over-optimistic, Cocker's own life-story is a classic tale of the outsider who overcame the odds to sit at the top of the world.

Born in Sheffield in 1963, Cocker was the son of an art school student mum and a musician dad who used to hang out with Joe Cocker and, whenever he could get away with it, pass himself off as his brother. By the time his sister, Saskia, came along, Cocker's mother was emptying fruit machines for a living, instead of making art. The first crisis in his life came when was five and had a serious bout if meningitis. The illness damaged Cocker's eyesight, so he returned to school sporting the dreaded National Health specs. The next one came two years later, when his father hopped it to Australia, never to be heard of again (until recently). Life from here on appears to have fallen into a pattern of ritual humiliation for the schoolboy. A swotty, speccy, beanpole and the only boy in class to have long hair, he suffered the further misfortune of having a relative in Germany who would send over Lederhosen to finish off the classroom ensemble. By the time he was 12, Cocker was coming straight home from school and spending the whole time in his bedroom, cripplingly shy and utterly introspective. He doesn't, he says, know what triggered it.

However, the time in the bedroom was well spent, with intensive guitar practise supplementing daydreaming in the school dinner queue. Cocker would stand there and endow his schoolmates with jobs in his band. He didn't actually tell them that they were his bassist, drummer etc. The flights of imagination just made life more interesting for him. By his 17th birthdy, though, an extra ordinary thing had happened. Cocker had got a band together, called Arabicus Pulp. "I was a bit of a child prodigy then," says Cocker. "We got a John Peel session, and I thought, 'This is it'. That was how I persuaded my mum to let me give university a miss and try to be a pop star instead."

No so easy. Cocker hung around Sheffield for years, releasing a few records that no-one took much notice of, signing on, being broke, frustrated and miserable. In 1985, he fell off a window ledge and shattered his leg. "I was in hospital for about two months. I had a lot of time to think about things and I had a kind of realisation that the way I'd been living my life, which was to basically deny what was happening to me by staying in bed all day, had to change. I'd though, if life is grim, then avoid it as much as possible by staying in bed - at least you'd have a nice dream now and again. Whatever. I was just avoiding everything, with this idea that one day I was going to leave this thing anyway.

"That's why I wrote Countdown [released as a single in 1990], which is about thinking of your life like you're a rocket on a launch-pad. The countdown's ticking away, and it's all right, all this shit can go on because eventually it's going to be five, four, three, two, one, we're off, and all that stuff doesn't matter any more. Then I realised that the countdown might never happen, and that even if it did, I'd be sitting there on the launch-pad, too decrepit to take off. All I was doing was wasting loads and loads of time. And so after that I then went the other way and started, like, going to supermarkets, throwing myself into things that I'd previously thought were useless and not important. Little details, things I'd thought were useless details at first. Weather and stuff, you know."

And eventually, like the sleeping pop prince that he was, he woke up to reality. He moved out of Sheffield and enrolled at St Martin's School of Art to study film. This, of course, is what he should have done in the first place. After all, it's just something that anyone who wants to become a really big British pop star has to do. In fact, you can, in an idle moment, construct a pop renaissance theory whereby every time there's a huge surge of classy pop activity in Britain (like now), there has to have been some confused schoolboy dreaming of pop stardom, going to art college, and joining a group somewhere near the beginning of the decade - so John Lennon in the Sixties, Glen Matlock in the Seventies, Jarvis Cocker in the Eighties and Damon Albarn in the Nineties. Except that Cocker, the idiot, missed his window. He despises the Eighties and the attitude to pop that is produced, without even twigging that it was All His Fault.

Anyway, moving to London, and to art college, worked out better than he could have hoped. "The system they seemed to employ at St Martins was a kind of right-on Noah's Ark system where they took two of each - sexuality, race, geographical persuasion. So me and a guy from Liverpool got put on as a couple of token northerners, kind of thing. Every minority group was represented in this class of 20 people. And that was probably the best thing they did, cause you were then in with a load of people who were completely outside the experience that you'd come from."

"It was great, it really focussed me on what I was. Before I left Sheffield I thought maybe the whole world was like that. I didn't believe that the class system existed. Suddenly you had to think about everything again, and what was important to you and how you saw things. That's what made the band really. Gave us material."

The professional watershed came in 1989. A single from the album, Separations, which had been recorded five years before and shelved when Rough Trade went into receivership, was released and became NME's single of the week. "That was the beginning of the new era," Cocker told The Face. "We got invited to play concerts again and the scene was totally different. And people actually liked us. Significantly, it was the beginning of the Nineties, and things started to go on an upward slope. Even though it may have been a very small gradient and you wouldn't have bothered to put a warning sign on it"

From then on Pulp began to follow a similar trajectory to the one envisaged by the 17-year-old Cocker, until by 1994 they'd gone platinum with their wonderfully sex-flated album, His 'n' Hers, and been shortlisted for a Mercury Music Award (Cocker recited the entirety of John Miles's mawkish Music Was My First Love instead of making a speech at the award ceremony).

But real fame, Boy George-style attention, was yet to start building. And it arrived, like a bolt from the blue, with a single song, Common People. Released in May, against the better judgement of Island Records, who felt it to be too far in advance of the new album, Different Class, which was nowhere near complete at the time, it went straight to number two, cruelly denied the top slot by those two guys from the TV series Soldier, Soldier. The song has become an anthem. Detailing an incident during Cocker's inspirational time at art school, it pokes fun at middle-class types who find appealing the idea of roughing it while they're students. The lyrics are full of scorn, the delivery is deadly, the choruses are rousing: "You'll never live like common people, you'll never do what common people do, you'll never fail like common people you'll never watch your life slide out of view, and dance and drink and screw because there's nothing else to do." Or: "You will never understand how it feels to life you life with no meaning or control and with nowhere left to go. You are amazed that they exist and they burn so bright that you can only wonder why."

"I mean, it's the worst insult, isn't it, calling people common?" says Cocker. Yes. "Like, if someone's eating with their mouth open or something?" Actually, that is pretty common.

It wasn't until he was confronted with the spectacle of 100,000 people knowing the lyrics and singing along at Glastonbury that Cocker realised just how powerful the song really was, and how much power it was going to bestow upon him. And it wasn't until some weeks after that, while the band was recording the rest of the album, that he realised that this too could have its downside.

"He just wandered in off the street", says Cocker, "really broad Scouse accent, going, 'Are you the vocalist?' I said 'Yeah' and he said 'That's about me, that song, that's about me.' I said 'Is it?' We realised he was a nutter. He hung around all day going, 'You know, man, you know ' and that was quite weird. I thought he was going to do a Mark Chapman or something. People get funny ideas, don't they?"

The one major piece of unwelcome fame-fallout that Cocker has undergone lately is a front-page splash in the Daily Mirror. Last month the paper ran a campaigning piece headed 'Ban This Sick Stunt' and running a readers' phoneline, asking whether the "pro-drugs" single Sorted For E's & Wizz should be banned. The song in question is by no means pro-drugs. It's hauntingly ambivalent, the work of an adult who knows what he's talking about. Sorted For E's & Wizz takes a backward look at the late eighties rave scene, and tends towards the judgement that although all involved at the time really did believe they could make a better world, it was ludicrously na´ve not to click immediately that ideas of summers of love didn't amount to a hill of beans. There's a point in the song where Cocker drops into spoken-word phrasing - which he does quite often and to great effect in his songs - to say: "And this hollow feeling grows and grows and grows and grows and you feel like calling your mother and saying, 'Mother, I can never come home, because I seem to have left an important part of my brain somewhere, somewhere in a field in Hampshire.'" If you've ever taken Ecstacy, the feeling is instantly recognisable, as is the worry expressed in the dying fall of the song: "What if you never come down?"

So, it's a useful and thoughtful song about drugs, which are talked of only as a menace in the mainstream, while around two million people are taking them every weekend. There must be a way of pulling together these adversarial strands in our culture, and it's a good thing that no one actually stopped Jarvis Cocker from making his point. Although the record's cover, which featured a home-made wrap for carrying speed, was withdrawn, the single wasn't banned.

The mirror coverage was silly, but it does point up the contradictions in Cocker's position, and the problems that arise when you lose a decade. Within a few days of the Mirror story, Daniel Asthon, a 17-year-old schoolboy, became the 51st person in Britain to die as a result of taking Ecstasy. Vindication for the Mirror, whose readers voted 2,112 in favour of banning the record and 770 against? Not really, but more food for thought for Cocker. He is, for the moment anyway, in a position of influence over some extremely young people. Succumbing to that position would compromise all of his quite correct beliefs about pop - that it should be spontaneous and unselfconscious, and that it falls apart when taken seriously. And anyway, he has, like many perfectly sensible adults, used drugs sometimes. It's not that he thinks they're such a good thing - he doesn't. But like booze, they do deliver a good time and for lots of us that's irresistible, even when it's killed or damaged people close to us.

Cocker doesn't intend to declare that he will never touch drugs again. But at the same time he doesn't want the tabloids following him around till they find him in a toilet with a tenner up his nose. His life has already become circumscribed by fame. With Different Class - an instant classic that's bound to sell forever - coming out at the end of the month, media attention is going to get more and more overwhelming. So, we're back to the same old question. Has intense never-off-children's-telly pop fame come too late for Jarvis Cocker? Or can being a grown-up be more of a help than a hindrance?

Cocker believes that while the timing of his ascent has its difficulties, it would have been a disaster if it had come along when he first believed it would. "I was just a kid. When we made our first record, I hadn't even had sex. I was writing about it but I hadn't done anything. I mean, the interim living was... was useful. I think that this enforced bit of living in the real world that the group all had to have - the fact that we know we can survive doing that even though it wasn't so great - means that, unlike people who've got famous when they're 18 or something, we can fall back on real life."

Then there's the material. Cocker has a dream of ending up writing about his life now, which is largely gig, hotel room, gig, hotel room. And so in his work he draws on life before fame, and how his perspective on it changes as his life does. "Until I moved to London I hadn't even thought about class, and I've been thinking about it a lot lately," says Cocker. "There a bit of an obsession with it on the new record, with Common People and I Spy, which is like the nastier side of Common People - getting class revenge by sleeping with a rich man's wife and stuff like that."

I Spy is quite biting, but it's also funny: "I Spy for a living. I specialise in revenge. I'm taking the things I know will cause you pain. I can't help it, I was dragged up. My favourite parks are car parks. Grass is something you smoke. Birds are something you shag. Take your Year In Provence and shove it up your ass." And while the candid sexuality which gave such an erotic charge to His 'n' Hers still crackles on the new album, Cocker's concerns have certainly widened. How far can Cocker go with the class warrior theme before he ends up sounding like bad-old-days Paul Weller ("See how mone-tar-ism kills, whole communiteee-es, even familee-es?")

"Well I don't know really. I mean, because no matter how clearly you explain something to someone, if they haven't experienced it themselves they can't comprehend it. Usually people don't stray outside the confines they're born into. It did make me irritated when I first came to London because I never really knew anybody who had much money when I was in Sheffield. But then you meet people who are in positions of power and stuff like that and you think, 'Well, I know people back home who have a lot more talent than you and are just sitting at home doing nothing. They deserve this. You don't.' But that's something I really think you have to guard against because then you get into the thing where you're only hanging around with northerners, only going to pubs where they sell Tetley Bitter, and 'I want my chips and Yorkshire fishcake every night.' There's nothing to be gained from that either."

"It's a problem because that desire to escape gives you a lot of impetus, a lot of power. You use that and you escape from this background that's been clinging to you and holding you back. You realise that as well as being something to struggle against, this was actually fuelling everything as well. And so suddenly you're a car with no petrol. That's why loads of groups fuck up, because their driving force isn't there any more. You've escaped. But what do you do when you've escaped? You might feel a sense of frustration, a bit impotent, but it turns inward then because you wonder what you actually are. You're cut off from where you've come from, but it's still the only thing you feel comfortable with because other people aren't going to accept you, no matter how much money you've got. And if they do, you feel like you're being patronised. I mean, do you think there's any solution to this thing?"

No, not really.

We're sitting around a mellow refectory table in a big old house near Ipswich. We're in the kitchen of the Peel family, whose home is just Enid Blyton for grown-ups. There's lashings of red and white, the dining table next door is groaning with glorious food, and conversation is flowing. John Peel has taken the unusual step of inviting Pulp, along with the production team of his radio show, down to his home to record a particularly redolent John Peel Session.

The whole family is here. The four Peel children are staying in specially. The BBC crew has arrived. Sheila Peel's sister has come over. Nick Banks is down, and so are a couple of nice blokes from Melody Maker. The dogs and cats are hanging out happily, and so is the rather dashing boyfriend of Alexandra, the second eldest Peel child. Alexandra's lush blond look would rather put you in mind of Courtney Love, if at 17 she didn't come across as a good deal more mature than the Hole vocalist. She won't be passing out at too many concerts, that's for sure. The show's producer teases Peel about his low-tech recording equipment - he likes it that way. Peel despairingly displays the 100-yard piles of CDs that have been sent to him recently. I get detailed to help out Flossie, the youngest girl, with her creative-writing homework.

And Jarvis Cocker lays one demon to rest. For years after the precocious session of 1981, Cocker has rather held against none other than John Peel the mess his life had become. After all, the 17-year-old's easy procurement of a coveted session had given him delusions of grandeur, so he hadn't prepared properly for his Oxbridge interview - he tried to pretend he'd read a Thomas Hardy novel that he hadn't - and he'd deferred his place at Liverpool University for so long that it had eventually been withdrawn. Peel is touchingly apologetic about what he sees as his decade-long neglect of Pulp. But there's no denying that the replaying of the first session, compared and contrasted with selected tracks from Different Class, plus conversation at last between Peel and Cocker, make for great radio.

After the show has been recorded, the older and the younger man sit round the dining table. Talking amiably about their experiences in the pop world. They're both relaxed, they're both wry, they laugh and grin their way through instant rapport. Between them, they have everything in perspective. They know what they're about. Class anxiety, generational strife, the pressure to set yourself up as a role model, the unwanted attention that comes with fame - all of it melts away. Chat goes on until it's too late to put off the return to London any Longer. So it's goodbye to Peel Acres - as the man himself fondly refers to his pile - and off through the night, back to the city where Jarvis Cocker finally made it.