Ten Questions for Jarvis Cocker

Ten Questions for Jarvis Cocker

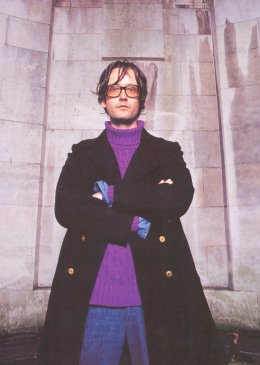

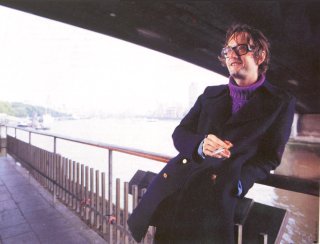

Words: Jim Irvin, Photographer: Jamie Beeden

Taken from MOJO Magazine, November 2001

Mojo grills the willowy Pulp frontman about Scott Walker, Ginster's pasties and encounters with his younger self.

Are you happy with this record?

Yeah, I am. It was finished by the end of March, so I was slightly worried that I might have gone off it by the time it came out, but I haven't, so that's a good sign. [With Scott Walker producing it] I was a bit worried because history - as I'm sure readers of MOJO will know - is littered with combinations that should have been great but aren't. A mate of mine has this bootleg of Jim Morrison singing with Jimi Hendrix in a bar in LA, and it just soulnds like some pissed-up blokes mucking about. So, obviously, I didn't want that to happen. But he honed in on the atmosphere of each song and found ways of bringing it out. He illustrated our book. I know that sounds poncey, but it was really like that. He was very good at coaxing decent performances out of us.

How did you feel singing in front of Scott Walker?

I was terribly nervous. I'm not the biggest fan of my own voice. But he was good. He encouraged me to sing out. He didn't give me any specific tips like, 'Drink camomile tea and take lots of deep breaths,' but he made me face up to my singing. My basic method in the past was to get semi-pissed, go into the vocal booth, do five or six takes - while still drinking - and then leave it to the producer to composite the final version from the best bits. But Scott didn't like me to sing too late in the day, certainly didn't like me being pissed and [made me focus] on getting the performance right. So I was more involved in it, rather than leaving it to somebody else to sort out, and I realised I didn't have to be hammered to sing.

What do you feel about This Is Hardcore now?

I think it's good. But it's not a record made by a contented people. It's a record about disillusionment. If you're serious about what you do, how you're feeling has to come out in your music, so I'm pleased that we didn't try and gloss over it and carry on as if everything was fine. It was coming after a really big record, so there was all this expectation, some from us, but a lot from the record company. There was a lot of pressure, but this time there was no pressure, really, because nobody was arsed! We could have easily said, Let's not make another record. We had to ask, Do we want it to be such a laborious, painful process again? And none of us did, so everybody kind of changed their lifestyles and I went off for walks in the country.

Weeds, on the new album, We Love Life, is about people on the margins being exploited by pop culture. Is that how you felt?

The thing that can be really demoralising about getting some kind of success is that people, and I certainly did this, start a group because they're marginalised and it gives them something they're in control of, their little fantasy world to escape into. Then, if you do make a breakthrough, it's taken away from you, it becomes something that's marketed and sold and you feel like you don't own it anymore, you feel like a bit of a caricature of yourself.

I think stuff comes from poor backgrounds and then gets exploited by people and [the originators] don't get any benefit from it. Like Kool Herc, who everyone acknowledges invented hip hop and he's stuck in some shit apartment in some project - where's his gold Ferrari? It's just not realistic. They think these people are scum but when they want to score some blow they'll go round to their houses and then say afterwards in their private club, (adopts posh voice) 'I went to this council estate today, it was really, really authentic.' This kind of slumming-it vibe exists quite a lot in our society now. Like middle class people going to football games: 'Yah, so, just tell me the rules again. Which side should I be shouting for?' It does bug me.

How much does your job involve Jarvis the pop star feeding off Jarvis the person?

That's OK, as long as you realise that your life comes first and that anything that you create comes from that. If music becomes your career it shouldn't become your life. Life is like the car, and your art, or whatever you produce, is a caravan, and as long as the car's in front of the caravan you can go places. The other way round, you're not going anywhere.

Is being in a band a neat way of prolonging adolescence?

Definitely. A bit sad, seeing as I'm 38. I never wanted to grow up anyway, so this was a perfect career choice for me. [Steve Mackey and I] started doing this Desperate club, the name acknowledging that it's a fairly desperate thing to do at our age, set up a club. I've no ambition to be the new peter Stringfellow. One day I'd like to have children. It seems unnatural not to, but I worry sometimes that I'm getting a bit long in the tooth. You know, it might be handy to be around to watch them grow up, rather than shoot your load then die.

Do you listen to your own music for pleasure or read your fan sites on the net?

No, I bloody don't. No way.

Do you think the 1982 Jarvis would like what you're doing now?

I had a weird experience on the motorway about three months ago. I was driving my van and there was a yellow Hillman Imp in front of me. I used to have one of those, and so when I overtook it - and they're so shit anything can overtake 'em - I looked to see who was driving, and there was this kid with specs on, just sinking his teeth into a Ginster's Cornish pasty, which is exactly the kind of behaviour that I would have been involved in. It was only like a flash as I went past, so I'm not saying, I drove past myself on the motorway in a former existence, but it was really weird, and got me thinking about whether I would like myself now or whether I would even recognise what I am.

Actually, maybe the 1982 version of myself would be impressed with me, but I would find him really irritating. I'd say, You need to grow up a bit, mate, you need to get all that out of your system and sort yourself out and you might end up being not a bad person. At the moment you're all right, you're reasonably funny sometimes, but you're irritating. There was this thing when I had to move house once, I was packing stuff up and I saw this picture of myself on the cover of a magazine, I think it was Select, and I looked at it and thought, Who is this twat? I suddenly didn't recognise myself and thought, Is that really what you want people to think you're like. That was the dawning of a realisation that I'd over-exposed myself doing things that weren't what I was meant to be doing: presenting Top Of The Pops or being a rent-a-quote. Allowing that celebrity thing to undermine the fact that we make music. My intentions were honourable, though, your honour. At first it seemed to be like a crusade, to show that people from the alternative scene didn't have to be inarticulate, slightly autistic people. It felt important.

Actually, maybe the 1982 version of myself would be impressed with me, but I would find him really irritating. I'd say, You need to grow up a bit, mate, you need to get all that out of your system and sort yourself out and you might end up being not a bad person. At the moment you're all right, you're reasonably funny sometimes, but you're irritating. There was this thing when I had to move house once, I was packing stuff up and I saw this picture of myself on the cover of a magazine, I think it was Select, and I looked at it and thought, Who is this twat? I suddenly didn't recognise myself and thought, Is that really what you want people to think you're like. That was the dawning of a realisation that I'd over-exposed myself doing things that weren't what I was meant to be doing: presenting Top Of The Pops or being a rent-a-quote. Allowing that celebrity thing to undermine the fact that we make music. My intentions were honourable, though, your honour. At first it seemed to be like a crusade, to show that people from the alternative scene didn't have to be inarticulate, slightly autistic people. It felt important.

All that 1995 thing was about marginal stuff suddenly finding its way into the mainstream, and I thought in a naive way that it was going to make a difference, that things were going to change. A year or two later I realised that instead of you changing the mainstream, the mainstream's changing you. So I made a conscious decision to back off. I'm more comfortable now with the idea that you can produce stuff in your own little area and not get too hung up and whether all the world thinks it's great.

What do you fancy doing next?

Are you asking me out?

What's the biggest misconception about you?

That I'm miserable. In the last few years people seem to have decided that I'm miserable. And I'm not.

Ten Questions for Jarvis Cocker

Ten Questions for Jarvis Cocker Actually, maybe the 1982 version of myself would be impressed with me, but I would find him really irritating. I'd say, You need to grow up a bit, mate, you need to get all that out of your system and sort yourself out and you might end up being not a bad person. At the moment you're all right, you're reasonably funny sometimes, but you're irritating. There was this thing when I had to move house once, I was packing stuff up and I saw this picture of myself on the cover of a magazine, I think it was Select, and I looked at it and thought, Who is this twat? I suddenly didn't recognise myself and thought, Is that really what you want people to think you're like. That was the dawning of a realisation that I'd over-exposed myself doing things that weren't what I was meant to be doing: presenting Top Of The Pops or being a rent-a-quote. Allowing that celebrity thing to undermine the fact that we make music. My intentions were honourable, though, your honour. At first it seemed to be like a crusade, to show that people from the alternative scene didn't have to be inarticulate, slightly autistic people. It felt important.

Actually, maybe the 1982 version of myself would be impressed with me, but I would find him really irritating. I'd say, You need to grow up a bit, mate, you need to get all that out of your system and sort yourself out and you might end up being not a bad person. At the moment you're all right, you're reasonably funny sometimes, but you're irritating. There was this thing when I had to move house once, I was packing stuff up and I saw this picture of myself on the cover of a magazine, I think it was Select, and I looked at it and thought, Who is this twat? I suddenly didn't recognise myself and thought, Is that really what you want people to think you're like. That was the dawning of a realisation that I'd over-exposed myself doing things that weren't what I was meant to be doing: presenting Top Of The Pops or being a rent-a-quote. Allowing that celebrity thing to undermine the fact that we make music. My intentions were honourable, though, your honour. At first it seemed to be like a crusade, to show that people from the alternative scene didn't have to be inarticulate, slightly autistic people. It felt important.