Now you've found success, is it any good?

Now you've found success, is it any good? Common As Muck!

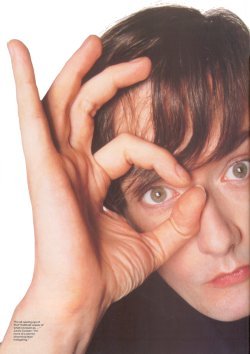

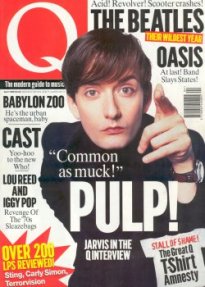

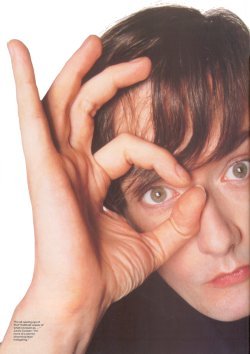

Common As Muck!Considerably older and several notches wiser than the average icon, Pulp's Jarvis Cocker stands freshly crowned as Britain's best-loved pop star, peering through the cracks in society's grubby walls and selling shed-loads. "I'd probably end up like a monk," he tells Phil Sutcliffe.

Pulp landed in Sweden last night, but they're still coming down from Japan. Circumnavigational jet lag vies with cultural bouleversement for command of the mental flight deck. Naturally, being British, as they settle into their Stockholm hotel's handsome restaurant, the first tale on every tongue is a ghastly recollection of the mealtime when a large and unhappy fish lifted its head to gaze accusingly at the Occidentals who, in a cosmopolitan spirit of enquiry, were eating it alive. Yet, the whole band seems to be enamoured, enchanted and talking "Japan, best tour yet" - which is quite something when you've been on the road, after a fashion, for up to 15 years.

Russell Senior and Jarvis Cocker are particularly struck. Characteristically, the guitarist examines the experience with a fierce intellectual rigour, while the singer peruses it much more whimsically. "I've never learnt so much in a week, never felt more like a pop star, and never felt so good about being a pop star," says Senior. "My belief in the inherent supremacy of Western European culture has taken a severe knock. And it wasn't an ill-thought-out belief. I thought Japan was an insect nation, that there was a lack of individuality, but they're actually more personal than we are - they notice the tiniest details about you."

He says that their choice of gifts proves the point. Cocker offers evidence. A girl gave him some matchboxes, which she'd made herself, with pictures of dogs on the upper panel. Outlandishly inscrutable? No, she'd studied the subject. He collects the British brand that deploys this same canine motif - "I know it's a very sad hobby to have," he allows. She'd read of his disappointment at never being able to get the full set.

It's a "lobby-day", as Pulp call it. The gig's tomorrow, it's a blue nine below zero outside; the options, according to mood, are wait and get frustrated or relax and enjoy (at least a bit). Pulp tend to the latter turn of temperament. After all, when it comes to resilience, they've had more practice than virtually any band in British pop history. Indeed, if you could squeeze it between the u and the l, Gumption would be their middle name. Chronologically disoriented and idiosyncratically glad-ragged for the photographers, they mooch about and take what consolation this wood-panels-and-chandeliers, open-all-hours-style establishment has to offer: Namely, alcohol of every stripe, elegant and wholesome Scandinavian scran and the odd game of blackjack or roulette at the lovely Katya's Casino in the corner.

Despite swirling fatigue, the Pulp family of friends - an equable, warm, free-flowing democracy - seems in pretty good working order. The only thing is (and this is not a discordant note), you can't help noticing that Cocker is a star. He is now, at any rate. Quite probably in his days of obscurity he was indeed obscure, light well bushelled. But these days, whenever he drifts by, you stare.

He is the man who started Pulp, at a theoretical level, during an Economics lesson in 1978. The long streak of nothing in the navy blue blazer, matching turtleneck and, if his trademark taste for the tacky persists, not velvet but velveteen trousers. The lad who grew up with women because his father stepped out of his life when he was seven; who dreamed until his early twenties of being an astronaut; who was always getting picked on by rougher kids because of his gawky body, bad eyes and different-drum behaviour; who, by his own public account, has always been so abysmal romantically that he started writing songs about sex because "I though I might be in danger of forgetting what it was like"; who, apparently, they all want to shag now.

Here's Jarvis Cocker ready to be interviewed. He talks in fluent, long paragraphs with a mild Yorkshire accent and just the odd dash of colloquial grammar. He frowns strenuously as he considers each question and marks each bon mot with a smile that occurs only around the mouth. This suggests nervousness rather than insincerity. The strong impression is that his durability rests on some of the most straightforward honesty you are ever likely to encounter.

Now you've found success, is it any good?

Now you've found success, is it any good?

We never wanted to be a cult band. We always wanted to be a pop band. It's just that we were quite bad at it before. But we've become successful without particularly changing what we did. I count that as an achievement. Some bad things come along with it, though like if you work at Sellafield there's the radiation to think about. I never really realised the importance of having a private life until the end of last year. Newspaper stories about who you're shagging, that stuff's not so great. I'll probably end up like a monk because people'll recognise me if I indulge in surreptitious illicitness.

Is failure good practice for making it?

Well, when we weren't really very popular, the group gave me an excuse to be alive I suppose. It gave my life a bit of form. When I was really young, I just wanted success because I thought it would mean you didn't have to make an effort any more, and that everything would be laid on.

A kind of Heaven?

No I think it would be hell really.

Have you worn fame well so far? Any disgraceful acts?

I dunno. One of the weird things about it is the more you show your arse at public functions, the more people like it. The only way you can really disgrace yourself is by being dead boring. It's hard not to bland out, tolerate people you shouldn't tolerate. You have to remember that the impetus for you existing isn't to be a celebrity and play golf with famous people. There is this tendency for success to take the rough edges off life. For instance, it worries me that I can't just go out to the pub any more - though it's more irritating for the people that I'm with than it is for me. If they send you to get some drinks you're gone for about an hour because people keep talking to you. Your friends wait while you hold court.

Do you throw your weight around, get angry with people more often?

I'm not a demonstrative person. I avoid anger or any kind of confrontation at all costs. Which is probably not a good trait. It means that when I do get angry it's a big one, chucking everything all over the house. No, I like a quiet life. But that's another thing: it's not good to have people always accommodating you.

That's what happens to pop stars, though.

It's crap. I heard East 17 were going round Europe insisting they wouldn't eat anywhere except McDonald's. They should have somebody who can say, "Listen lads, that's a crap thing to do. Expand your horizons." But McDonald's it is. And terrible heart problems in later life.

You've had some tabloid hell already with the Mirror's ban this sick stunt front page lead about the diagram of how to make a wrap on the "Sorted For E's & Wizz" single sleeve?

It was the day after my birthday (his 33rd). When those kind of people take an interest in you, it's quite bad. They're very immoral. They rang up a bloke whose son had died at a rave a few weeks earlier and they're not offering sympathy, they just want a quote. Obviously he's going to say it's terrible because anything that reminds him of the way his son died is going to upset him. It was a horror story to be brought into the tabloid world. But it sold us loads of records.

Then The Daily Mail interviewed your father in the outback and quoted him saying he hoped you would forgive him.

That was a bit of a pathetic one. I even had the News Of The World offering to fly me out there and take pictures of me being reunited with him like bloody Cilla Black, Surprise Surprise. I was mad at my dad. It's a crap way to get in touch after 20 years. He could have written a letter. He knows my address. Doing it through a paper with pictures of him gazing into the ocean was a bit spewy. I don't really know what I'm going to do about it. I obviously can't help but be curious about my father. But, for better or for worse, I am a fully formed adult and I don't really see how knowing him would make a massive difference.

You're a storytelling songwriter, but when you become a public figure it seems you're telling two kinds of stories: The stories in your songs and the stories of your actual life?

Mmmmm. I write songs based on my own life anyway. That's giving quite a lot of yourself away to start with, and you're using people you've know because you write about them without asking their consent. The only way I can justify it to myself is to use something that's finished and gone. Then you're not hurting anyone too much I suppose. That's why it gets on my nerves when people want to delve further than that. I think that's enough from me. What I'd like to do is write about my past and keep my present secret. It's probably psychologically unhealthy to write about your relationships. It must show some kind of defect.

How are you with money now you've got some?

We haven't really go much yet. It's more than I ever had before in my life, but seeing as I was on the dole that weren't a right lot. And what the band makes is all split equally six ways, so nobody's any richer than anyone else.

Although you write all the lyrics?

Although you write all the lyrics?

I'm from the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire (seraphic smile). It's often money that splits groups up, isn't it? I don't know the right way to sort out internal politics in bands, but they're very fragile. You can think it doesn't matter if so-and-so leaves, but you get used to people being around. It's the Godfather syndrome. At the end of Godfather 2 Al Pacino has got absolute power and he's killed all his friends. Absolute power manifests itself in being absolutely alone, whereas my drive has always been to be more sociable than I am. I was quite shy and reserved as a kid. I know far too much about myself. I'd rather get to know somebody else.

Why do you think "Common People" was such a breakthrough for Pulp?

It was written in about June of '94 and the first time we played it it became clear to me it was a significant song. But then we had trouble writing the rest of the album. If you think, "Oh God, my livelihood depends on this chord sequence!" it can come out a bit stilted. In the end we forced Island to release Common People as a single before the rest of the album was done. I really felt - especially after being out of step for so long - if you had a song that was in the right place at the right time, then you'd be an idiot to let that moment pass. It seemed to be in the air, that kind of patronising social voyeurism, slumming it, the idea that there's a glamour about low-rent, low-life. I felt that of Parklife, for example, or Natural Born Killers - there is that noble savage notion. But if you walk round a council estate, there's plenty of savagery and not much nobility going on. In Sheffield, if you say someone's common, then you're saying they're vulgar, coarse, rough-arsed. The kind of person who has corned-beef legs from being too close to the gas fire. So that's what attracted me to calling it Common People, the double meaning, "Oh, you're common as muck" and then Emerson, Lake & Palmer's Fanfare For The Common Man.

The thing that had been eluding me was not that it had to be a concept album, but what the perspective or the take on things was going to be. Then I was staying at my sister Saskia's, falling asleep on the settee, and suddenly it came to me, the idea of dealing with my experiences in London and the differences between Sheffield and London. The other eight songs were done while Common People was in the Top 10. That state of excitement, knowing for once in your life you had a mass audience, gave us the confidence, certainly gave me the confidence, to bring certain things out of myself.

"Common People" seemed to be exactly right for Glastonbury?

"Common People" seemed to be exactly right for Glastonbury?

You struggle for such a long time in your life and then you end up headlining a Saturday night at Glaston bury when you weren't supposed to - we were only playing because John Squire (of The Stone Roses) had broken his collarbone, of course. And everyone sang along with Common People. That was a culmination in itself.

You were tenting it, weren't you?

Yeah, all the hotels in the area were full. We just spent the money we would have spent on rooms and transport on sleeping bags and six-man tents and set up camp backstage.

You touched a lot of people at Glastonbury because what you said was so genuinely optimistic, even aspirational.

I think the final thing I said was something about, "If you really want something to happen enough then it will happen" - if a bunch of idiots like us can do it, anybody can. If people can get that off us, I'd like them to.

"Mis-Shapes" felt like a companion piece to "Common People" at Glastonbury, but it's actually a more direct rallying cry - calling all misfits to fight back against the "Bully Boy's", "Townies" as you call them.

I've always had a problem with songs that tried to tackle social issues. I'm thinking of Another Day In Paradise, I'm thinking of Belfast Child. Mis-Shapes is probably the nearest I've got to a sloganeering song for the sake of it. I think I just scraped through because it's based on the feeling of a Saturday night in Sheffield when the beer monsters are out, wanting to smack you because you're wearing funny glasses, a funny haircut and orange trousers - and you have to run away.

But in Mis-Shapes you turn around and take them on with everybody singing "We're making a move, we're making it now".

It'll never happen, will it? The word comes from my mum buying mis-shaped chocolates. They were cheap because they wouldn't fit in a box of Milk Tray. I don't object to townies really, but the trouble is, they can't just get on with being ignorant in isolation. They want to take it out on other people.

There's a lot of hatred and vengeful feelings in your lyrics. It's not very nice, is it?

No. That surprised me. I suppose I Spy is the most extreme example, where revenge is taken on a middle-class person by sleeping with his wife - which attacks the very centre of his being, beyond the material advantages that can't be overcome. But I don't agree with the idea of revenge really.

"Common People" presents a picture of masses of hopeless, helpless and often pain-in-the-arse citizenry living their lives "with no meaning" - the working class?

There's no such thing as the working class any more in the old-fashioned sense, is there?

So they'd be called the underclass now?

And it's going to get worse, especially in terms of what's happening in the education system. The place I was brought up, although I'm not going to say it was the fuckin' roughest area in the world, it was quite rough down there. But I was able to have access to a decent education and I managed to escape.

Now you are talking like a liberal: education will sort it out.

No, what I'm saying is my axe to grind is not with the working class or the lower class, it's with the middle classes who through their selfishness are creating this situation. I didn't believe in the concept of class at all when I was in Sheffield. Then when I moved to London, I couldn't deny the fact that it existed. That's where the class obsession on this album started. But you don't want to become some sad, bitter person who moans on about how you can't get a decent fishcake down London. The line in Common People, "You will never understand how it feels to live your life with no meaning or control" - that's the most passionate part of the song.

There seem to have been two times in your life when you were faced with death, with intimations of mortality. The first was when you had meningitis as a lad and the other was in 1985 when you fell from a third floor window trying to impress a girl and broke your pelvis and some other bits. (Right: Jarvis pictured in Sheffield, 1986)

There seem to have been two times in your life when you were faced with death, with intimations of mortality. The first was when you had meningitis as a lad and the other was in 1985 when you fell from a third floor window trying to impress a girl and broke your pelvis and some other bits. (Right: Jarvis pictured in Sheffield, 1986)

With the meningitis I was too young to be aware of the danger. The accident did change my life, though it had a comic impact. I was hanging by my fingers from the window ledge thinking, "Right, I'm going to count one two, three, and then I'm going to let go". You'd think in a life threatening situation you might find that last bit of energy within you to pull yourself up, but I couldn't.

It wasn't dramatic at all. It was just ridiculous. If I'd died, it wouldn't have been a noble cause, it would have been a moment of stupidity and the end of it. In the hospital, I had a lot of time to think. And there was a miner in the bed next to me who'd been in an accident. He was a right nice bloke. The only contact I had with miners before was during the strike. I wanted to support it, but I always remember I was sat outside this pub and these striking miners came by and took the piss out of me because they thought I looked an idiot. Well, I did look an idiot at the time actually. So it was like, I support you in theory but you probably want to cave my head in. Of course, it was just four blokes, not the entire mining community. And I was guilty of generalisation and almost despising my own background. But meeting that bloke in the hospital encouraged me to think I'd been looking in the wrong direction for inspiration. I'd been in Pulp since I'd left school. I'd had this attitude of ignoring day-to-day things, I was hiding from life really, thinking I didn't have to deal with it because I'd become famous soon. I turned round the other way after that. I tried to get into the tiniest details of life, trying to scrutinise everything - I started to write lyrics that way too.

You often write lyrics about the painful aspects of your time in Sheffield. But what was the best day you ever had there.

(Ponders) It was 1987 and it was very simple. I had this inflatable dinghy I'd picked up in an auction for a fiver. Me and my girlfriend decided to go on an expedition down the River Don. It was a really sunny day and it was nice to see these bits of Sheffield we hadn't seen before. We stopped and looked round abandoned factories. A group of gypsy children chucked stones at us, then they started showing off by sledging down a weir on bread trays - I wouldn't have dared. The strangest thing we saw was a man attempting to shoot fish with air rifle. He was stood on the bank firing down into the water shouting, "Stitch that, you bastards!" We didn't go very far really, but it was an adventure. It fitted in with my idea that the everyday doesn't have to be this crushing concrete lump that oppresses you, that if you can be bothered to make the effort and look you can find excitement within it.

There sometimes seems to have been an element of "down and out in Sheffield and London" in your life - deliberately exploring the seamy side. In one interview you even said you were a drug addict.

That was a joke. But I did take drugs at various stages. In Sheffield there was the magic mushroom season. I remember going out to a place called Fox Houses on the outskirts to pick them. But the story behind Sorted For E's & Wizz is that when I went to London, living in a squat, I kept hearing about acid house parties and eventually I went to one in a hangar at this Santa Pod dragster raceway. We did some Ecstasy. The whole thing blew my head off. It was magical, especially because I'd left Sheffield where I felt I had the measure of the place and I wasn't sure about London - and my girlfriend had left me, just to get that one in as well.

We went to quite a few raves after that, though it was never as good as the first. In the end it came full circle: the one at Santa Pod where I got split up from my friends, as it says in the song, and suddenly all the people who'd been going "nice one" and "empathy", when you're trying to get a lift home they're all "No mate, sorry mate, no chance". The "common people" goes out of the window then. I couldn't believe it. I'd thought there was going to be some social change. Although I knew a lot of it was drug-induced, I thought people would somehow feel it'd be better to be nice to each other rather than looking out for number one all the time.

There's a typical Jarvis Cocker woman who crops up throughout your song writing career. One of her earliest appearances was in Little Girl (With Blue Eyes): "Little girl with blue eyes / There's a hole in your heart and a hole between your legs / You never had to wonder which one he was going to fill".

There's a typical Jarvis Cocker woman who crops up throughout your song writing career. One of her earliest appearances was in Little Girl (With Blue Eyes): "Little girl with blue eyes / There's a hole in your heart and a hole between your legs / You never had to wonder which one he was going to fill".

That's a bit embarrassing actually. It came from me finding one of my mother's wedding photographs, a picture of her getting out of a car, and the look on her face was very touching to me because I was already on the scene - internally. She looked very young and very scared. And then thinking of other relationships with women, I've never been a very good person to go out with. It's bad if you feel someone wants something from you and you're not capable of giving it to them. It's a thing I don't really like about myself. A certain coldness. I try to fight against it, but it recurs. I try to impose some kind of meaning on whatever I'm involved in. I know my life doesn't have a story, but I can't stop myself from wanting it to add up to something and that can be a bad strain to put on a relationship.

The typical Cocker man crops up on Blue Glow. "Crouched down behind a bush at the roadside I watch as you pass by me." A lot of your men are voyeurs.

That's true. I'm more of a one for observing that instigating. If you arrange to meet somebody you're going out with at a train station, it's nice if you can get there early and hide and watch them arrive. I've done that on a number of occasions. You see them the way somebody else would see them. It reminds you of when you first saw them and the way you felt. After that I do go and make my presence known (small smile).

Are you the marrying kind?

When I was younger I always used to say I wouldn't get married because I couldn't see any examples of it working out. Now, I've changed my mind. But I think I'd have to retire from writing songs. Otherwise I'd be putting my marriage in my lyrics. It just wouldn't be right. It would be horrible. In my mind it's a bit of an either/or situation. I'm trying to work it out because I think I'm heading for a fall if I don't sort it out. Quick.

Art or life? It's a teaser, all right, especially given the peculiarly confessional demands of Jarvis Cocker's creative instincts. However, his track record encourages the hope that, should he muck it up a time or two, he'll pick himself up after the prat-fall and proceed as ever in the general direction of getting it right next time (or the time after). Jarvis Cocker is not "an improbable hero". He's absolutely no hero at all. Yet somehow he and his band really are an inspiration. Not necessarily undefeated, but unvanquished. And not just spirited, but still intelligent, combative, thinking on their feet, constantly replenishing their reserves of optimism each time naive expectation comes to nothing.

"It's all random," as he once philosophised, "but once you realise that, it's quite good."

|

Joined 1984  |

How have you taken to being a popstar? Not too badly, though I had a horrendous night last year in France. I went on stage after drinking this frozen tequilla. When it hit me I felt really weird. I'd got a Christmas tree and a teddy bear that fans had given me beside the keyboards, and every time I stood near them I felt OK and every time I was at the other end of the keyboard I thought, "In a minute I'm going to walk offstage". I thought I was going mental. It was scary. It seems important that the band writes the music together before Jarvis does the lyrics. |

|

Joined 1995  |

Officially you joined Pulp last year, but do you go back a long way? When I was 15 and a half I decided that I wanted to write a fanzine. I lived in Chesterfield. Pulp played at the Arts Centre and I interviewed them. They were totally weird. Jarvis had just had his accident and he came onstage in a Victorian wheelchair. He performed all the way through, then at the end he stood up and walked off. I got to know them and over the years I helped out with the light show, ran the fanclub and became the tour manager. From 1992 I was playing second guitar on stage and on Different Class I got involved in songwriting. Last summer they had a big meeting. They gave me this once-in-a-lifetime offer. I was flattered and shocked. They didn't have to do it. |

|

Joined 1983 (Left 1997)  |

In 1992 you said: "This kind of failure is like having a boot stamped in your face repeatedly. Watching all those snot-nosed little shits getting famous while you're not!" I was paraphrasing George Orwell. I think that the original goes, "If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping a human face for all infinity". The feeling was acute. Though there were always people-albeit a small number-coming backstage and saying, "That changed my life". You did business administration at university, didn't you? I could have had a glittering career in the commanding heights of British industry. What a mistake! In fact, I did the band's books for years and I think we would have ground to a halt - to blow my own trumpet - if I hadn't been such a hardline Stalinist whipper-in. Are Pulp a civilising influence? Definitely. Someone said about architecture, "A building should elevate the human spirit", and that's Pulp's intention. I do believe there's a battle being fought between high culture and barbarism. I see us on the side of high culture. You may think it's a load of toss and you're entitled to. What's your personal contribution? Lemon juice. You wouldn't want a glass of it, but it adds piquancy. |

|

Joined 1988  |

Did you ever think you and Jarvis were more likely to end up as filmmakers than pop stars? It could have happened. I went down to London the year before him. I lived in a squat in Camberwell. When he came down to start his film course at St Martin's, I moved upstairs and sold Jarvis the key to my old place for £150 - it sounds terrible but it was the cost of the security door we'd put on. Later he asked if I'd like to join Pulp. It was no big deal. They were a band without a career. "Want to be in Pulp?" "Yeah." At the same time, me and Jarvis had a film company. We sold a film to Channel 4 and we did videos for Tindersticks and The Aphex Twin. Do you think Pulp are a civilising influence? |

|

Joined 1986  |

Is it true that your bass drum is full of knickers and bras? It has been. Girls throw them at Jarvis. A section of the flight case is packed with underwear - style gifts. When you were playing to tiny audiences, were you any good? What was your best moment with Pulp? |