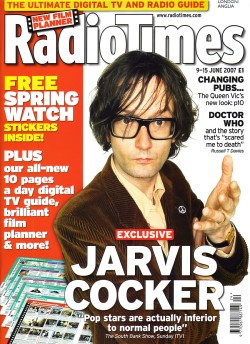

Specs Appeal

Specs AppealWhat's finally made quirky pop icon Jarvis Cocker come over all mellow?

He has a grand life, does Jarvis Cocker. He lives in a Paris apartment with his French stylist wife Camille and their four-year-old son Albert, maintains a London bolt hole in bohemian Hoxton, and only does the work that interests him. He's recognisable enough to attract comments from people in pubs, acclaimed enough to be curating this year's Meltdown music festival at the Southbank Centre in London, and is the subject of a South Bank Show profile on ITV1, but he's anonymous enough to walk from home to our interview without wearing shades.

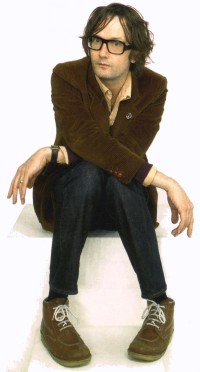

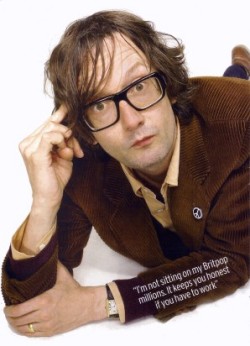

He has changed very little since his glory days with his band Pulp. The uncombed hair is the same length, there's no extra meat on his bones and the spectacle frames, which he has a habit of slowly pushing up the bridge of his nose when he needs extra thinking time, could have been bought at any time over the past 20 years. Despite the hits, the notoriety (more of which anon) and an advert for BT, he claims that he's not particularly well off. "I'm not sitting on my Britpop millions," he says. "It keeps you honest if you have to work."

He's unlikely pop star material. He's the wrong shape, the wrong height and has the wrong features. To cap it all, he has an aversion to celebrity. "I think pop stars are just people, and I hate it when they act as if they're not, or even as though they're somehow superior," he says. "In most cases pop stars are actually inferior to normal people because they live such a pampered existence."

As a gangly kid with glasses and strange clothes growing up in Sheffield, he was a target for playground abuse: "four eyes", "lanky", "look like a girl". He defended himself with wit and humour, and found solace in books and music. His salvation came at the age of 13, with punk rock. "Before that I'd wished I could fit in more, but the whole message of punk was 'Don't be a sheep. Don't follow the crowd. It's good to be different. Invent your own style."' He learned how to alchemise his supposed weirdness into style. "I realised that everyone had been dealt a certain hand and so you had to make that work for you. If you're thin, instead of wearing baggy clothes to cover up, you wear tight clothes to accentuate it. You turn it into a fashion feature."

Being different provided him with a good vantage point from which to observe. It was the making of him as an artist. The daddy-longlegs with specs became the fly on the wall with a notebook. He started writing songs in order to discover who he was and what was happening. "A lot of my time is spent trying to sift out how much of my idea of the world has been shaped by media and how much bears some relation to reality," he says. "Songs are my attempt to make sense of life. I don't keep a diary or a journal. I hardly ever take photos. Writing songs is my way of remembering things."

His mother, a former art student, encouraged his disapproval of convention. His father walked out of his life when he was seven. He didn't feel resentful, or at least he can't remember feeling so - but he did start taking time off from school. Twenty-five years later he and his sister, Saskia, traced their father, Mack, to Australia, where he was working as a world-music DJ. They bought tickets and flew out to see him. Mack was aware of his son's success but had never made contact. "If this had happened in EastEnders we'd all have been in floods of tears and declaring how much we loved each other but it wasn't like that at all. Although we're biologically related it was like meeting someone I didn't know. We just didn't have the normal parent-child relationship."

The three of them have since stayed in touch. It didn't supply any missing pieces to the puzzle of Cocker's existence, but it did erase some illusions. "It was weird," he says. "Although we were estranged I had, over the years, built up a picture of the sort of man I thought he would be and then I was faced with the reality. It was difficult to adjust." He made contact, he says, "for selfish reasons". A friend's father had died suddenly and Cocker began to wonder how he would react if he heard that his own father had died. I know I would have felt bad that I'd never known him. If I hadn't had the meeting it would have gnawed away at me."

Like many people once deserted by a parent, he appears determined not to repeat the mistake with his own offspring. He's just back from an American tour for his debut solo album, Jarvis, and when he arrives for his Radio Times photoshoot his hands are covered in ink left over from a creative early-morning romp with Albert. "Having a child forces you to acknowledge the fact that you're involved with society," he admits. "I've always been a bit I 'anti', a bit 'I don't believe in this society', pretending that I'm not involved. Then you bring a child into the world and you have to face up to the fact that you are. Then there's the vulnerability. I've developed a big sentimental streak. When I see images of starving kids in Africa on TV I become a blubbering wreck. Before, I could just watch and think, oh, that's a news item."

Cocker has clearly mellowed. He frequently refers to his age - 43 - or curbs himself from making a scathing comment on the grounds that he doesn't want to come over as a "grumpy old man". On his iPod at the moment he has only the songs of Leonard Cohen and the poetry of John Betjeman. The usual suspects don't seem to arouse the usual ire. David Cameron? "I can't imagine I'd be convinced by him." Gordon Brown? "We'll see." Live 8? "I don't doubt their motives." Pop Idol? "Not even worth mentioning."

Actually, he thinks Pop Idol, and programmes like it, represent the death of music as he once knew and loved it. "They never pick people with great voices," he argues. "They pick people who show off how many notes they can fit into a ten-second period. A great voice expresses something and gives you some idea of the personality behind the voice. There's zero personality in the voices of any of the people who sing on these shows."

Jarvis Cocker, he readily admits, wouldn't make it past the regional heats in reality TV. "I'd be straight out," he says. "It saddens me, because I love pop music and these shows prove that it's become an industrialised process. I hate that. The kind of pop I was brought up on is over. In those days there was space within pop for interesting things to happen like Laurie Anderson making number one with O Superman - but now I don't think there is. The pop charts used to be where everything happened. Now the most interesting stuff is happening outside in the independent music sector. I can't say I'm 'annoyed' about it. It's just changed. I'm old. For me to get annoyed would be like a pensioner being annoyed that Glenn Miller is no longer in the charts. Things move on."

A few years ago Cocker used to get annoyed. Famously, he got annoyed in 1996 when Michael Jackson came over all Messianic at the Brit Awards, storming the stage and shaking his bony butt at the superstar before security escorted him away. He hasn't changed his mind about the validity of the protest, but he regrets the attention it brought him. "I got too much publicity," he says. "There is an obsession with celebrity in our society, but I think people are starting to realise that it really isn't very nice. Some people might thrive on it, but I didn't. To suddenly become known by a lot of people simply because I waggled my arse at somebody isn't brilliant, is it? I'd rather be known for something better than that. Although my arse-waggling is second to none, I would rather people remember me for what I create."

Jarvis on...

Politics

"Either you think you can change the system from within or you think the system is so corrupt that we need a new system. I tend to favour the latter."

Poetry

"Poetry is something I've come to value. I didn't used to get it. I think when you're younger your mind works in a more straightforward way. Now I'm older, I get it."

Work

"I've never held down a proper job. It's not something I'm proud of. It's just a fact."

England

"I have all these fond memories of England, but then I get to the Eurotunnel terminal and there are these blokes with cars full of beer and it snaps me out of my reverie. It reminds me of the reality."

Joe Cocker

"If we're related, I'm not aware of it. My mother maintains that he fitted the fire in their first flat in Sheffield in the 1960s. He possibly babysat for me a couple of times."