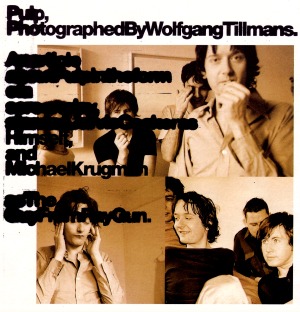

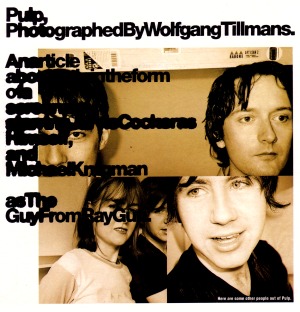

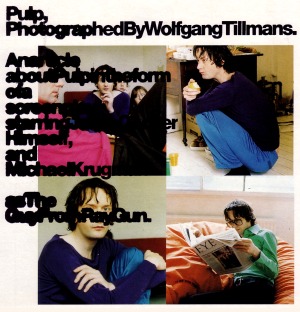

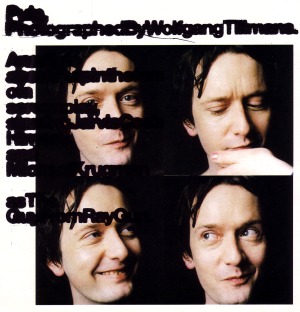

Deconstructing

Jarvis

Deconstructing

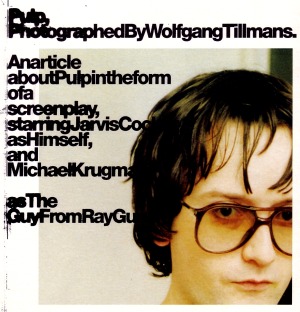

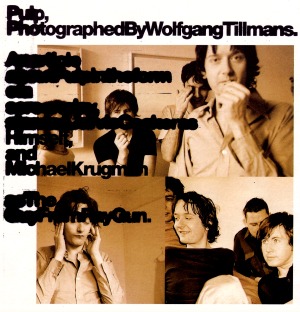

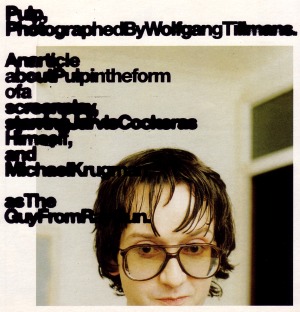

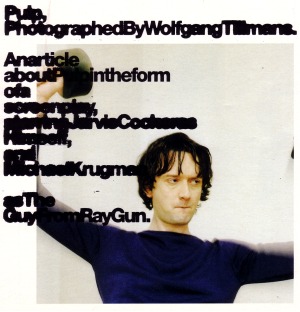

JarvisAn article about Pulp in the form of a screenplay starring Jarvis Cocker as himself, and Michael Krugman as The Guy From RayGun

"What exactly do you do for an encore?" sings Jarvis Cocker on the title track to PuIp's new album, This Is Hardcore, and as always, he raises an intriguing question. After more thon a decade in virtual obscurity, 1995 and '96 found Jarvis and Pulp finally rising up the ranks to become one of Britain's best (and best-loved) pop bands, a popular and critical success story that effectively dropped a ten-ton weight on the misfit sex symbol's tall but thin frame.

For those just joining us, Young Jarvis formed Pulp in his hometown of Sheffield back in 1978. In a classic piece of trivia-cum-foreshadowing, Cocker & Co. made a short film, The Three Spartans, before they'd played a single gig. For the next decade, Pulp were your archetypal indie student band, and a relatively average one at that. A handful of unremarkable LPs were released, featuring a revolving door lineup that numbered Russell Senior on guitar and violin; Candida Doyle on keys and synths; and the inventive rhythm section of Steve Mackey and Nick Banks. Then, in 1992, when no one would have expected it, Cocker wrote the extraordinary memory play single, Babies, and Pulp were born anew.

If Blur and Oasis were the Beatles and the Stones of the Britpop movement (Oasis, of course, were both, but that's another story), then Pulp were its Kinks. 1994's His 'n' Hers revealed the new Jarvis as a witty and urbane master lyricist, offering sly sex-mad commentaries about his life and the people he saw, backed by Pulp's brilliantine glitter-disco-synthesizer-art school pop. The band went from laughing stock to the toast overnight, and by the Summer of '95, in the heat of the Blur vs. Oasis battle, they released Common People, effectively trumping the competition with this sardonic, irresistible anti-anthem. Different Class soon followed, a masterwork of cultural criticism, suburban surveillance and sing-along choruses, the undisputed Best UK Album Of 1995.

Cocker, the archetypal four-eyed student nerd, became an icon, a beloved TV personality, pop god and social caviller as his country moved from Major and the Birth of Britpop to Tony Blair's illusory "New Britain." For better or worse, Pulp, Oasis, Blur, et al became the pop aristocracy of so-called Swinging London, having gone from underground pubs and clubs to tres chic ligging at fashion shows and film tests. It was a dream come true, of sorts. Jarvis Cocker had become one of the uncommon people, a glamorous bit of tabloid forcer, the stylish subject of stalking paparazzi.

"Aren't you happy to be alive?" Cocker, now 34 and not as idealistic as he once was, croons on This Is Hardcore. The thing of it is, for himself he's not entirely sure...

CUT TO:

INT. HOTEL ROOM. DAY

Jarvis Cocker, stylish as ever in his brown '70s specs, his hair longish, black velvet blazer, purple satin shirt, black poly trousers and some very fashionable sandals, sits sipping Evian on the couch in his suite at New York City's most European hotel, the guy from Ray Gun sits across from him, a notebook on his lap. The interviewer reaches across the coffee table and hits the record button.

Ray Gun: What brings you to New York?

Jarvis: There's this thing in the Puck Building, an Outsider Art Fair. Myself and somebody I went to college with - you know I went to film college at St. Martin's - we've been commissioned by Channel 4 in the UK to do three one-hour programmes on the outsider environment.

Ray Gun: What exactly is outsider art?

Jarvis: Well, outsider art is art that's produced by people who, as the name implies, have grown up outside the kind of normal cultural framework. For instance, they have never been to an art college. But also they're usually outside normal society. A lot of this stuff, when it was first thought of as a movement, was from people in institutions. In a way, the idea of having an Outsider Art Fair seems pretty horrendous, because it's stuff that is produced by people with no idea to having any value other than what it means to them. And yet, after it does acquire value, there's a kind of a weird kind of patronising attitude.

Ray Gun: Is this something you've always been interested in?

Jarvis: I got interested in it towards the end of art college. My course was mainly practical, but you did have Io write a thesis, which I wasn't very keen on. I was so jaundiced by the end of my time there that the idea of stuff that was produced with no eye to the main channels appealed to me. So it's been like, almost ten years. Now we're going to do this film. We're not trying Io take the scientific view of it. We're getting a car, hopefully a nice panelled four-wheel-drive-type of thing. Maybe even a Land Rover. We want to shoot the whole thing in sequence, so we'll start on the East Coast and just drive through various places ending up in LA. The journey will be as much a part of the programme as the places that we see. Instead of taking a high and mighty view of, 'Oh yes, what is this interesting phenomenon?' It's more involved in it, rather than being outside it.

Ray Gun: You've long been an outsider artist of sorts -

Jarvis: Yeah, that's true, yeah.

Ray Gun: Until fairly recently.

Jarvis: Yeah, yeah, that's true, yeah.

Ray Gun: And, even now that you're an insider, you're still pretty outside.

Jarvis: Well, I don't know. When we broke through in the UK - and it's only in the UK that we really broke - after such a long time, it was quite interesting to be allowed into the mainstream of society. 'Cause I'd always had a bit of an axe to grind about that, with growing up in the '80s and Mrs. Thatcher, the cult of the individual and "I'm alright, Jack," that mentality. We didn't really have much of a voice or anything, so when we all kind of broke through and went over-ground, it was exciting, 'cause I always thought it was bad for things to have to exist just in their alternative world. Now I'm not so sure. I don't know whether this is intrinsic with mainstream culture, with having to appeal to such a broad section of people, whether that means things automatically have to be diluted or watered down a bit.

Ray Gun: Pulp have become part of the new "Swinging London," showing up at gallery openings and premieres and so forth.

Jarvis: I didn't actually think it was swinging that much. I mean, there was lots of people going to these celebrity gatherings, and I got invited to those places. I went at first. I think you've got a natural curiosity to see what these things are like, and when you see TV chat show hosts eating, it's kind of funny. Then after a bit you realise that if you keep going to those things, you are going to become one of those people, with the slightly red pock marked face caught in the flashbulbs. And you have to decide: do you really want to do that? So I thought, 'No I don't, actually..."

The hotel housekeeper putters about Jarvis' suite before bringing a vacuum into his bedroom. To avoid the appliance's roar smothering the interview, the Guy From Ray Gun gets up and closes the bedroom door. As he pulls it shut, he spies a number of plastic bags filled with clothes, as well as a full-length fur coat sprawled on the bed. He sits back down and continues the conversation.

Ray Gun: Moving on to the record, what is Hardcore?

Jarvis: "What is Hardcore?"

Ray Gun: Hardcore is one of those words with so many different meanings, especially in America. I could be wrong, but the history of hardcore punk is net exactly the subject matter here, is it?

Jarvis: Well, I first came across the word in the late '80s, when I was gong to raves and things. I listened to pirate radio stations and they'd always be saying "Hardcore: You Know The Score!" and all that kind of thing. Se you've got "hardcore" as a "people in the know" kind of thing. There was always a kind of endurance test aspect to raves, because they would start at about 10 o'clock and just go through to morning or longer. So it was real hardcore if you were the one still dancing in the end. But really, the way that people achieved that was by taking massive amounts of drugs, so really there was a kind of sadness about it. if was just very scary to look in someone's face, because in their eyes you could see they didn't actually want to be dancing, but they'd got so many chemicals coursing around their body they just couldn't help it.

Ray Gun: Nothing else to do.

Jarvis: Yeah. I mean there was no other way to deal with this thing that was going on inside the head but to keep dancing. Then there is a kind of hardcore porn aspect to it. That came from touring and watching what's on the adult channels on the hotel TV. It's interesting, You get to see just how much each country allows, because you'd often see the same film. You see more in certain countries than others.

Ray Gun: You have different edits in different countries?

Jarvis: Yes. For instance, if you see the UK version, basically you'd just see faces. And people go, "Oh, yeah, ohhhh, oh, yeah." You don't see very much at all. That got me thinking about the way people kind of get used up in those films, and how they seem to just go through the motions. I thought that there was a certain kind of parallel with fame and stuff like that. 'Cause the last thing I would want to do in the world would be to make music just for the sake of it. If it didn't seem to be relevant at all, I'd rather just not do any.

Ray Gun: How did you deal with the great expectations placed on you? The weight of following up has broken lesser bands.

Jarvis: Oh, I know, yeah. The trouble is, if you have that as a factor in your thinking, then I think you're going to have severe problems.

Ray Gun: But how could you not?

Jarvis: Self-consciousness is the kiss of death. If you're thinking, 'Well, why am I playing this chord now?' you just can't get anything done; you have to get beyond that. And then if you're thinking, 'Why am I playing this chord now and how much money is it going to earn?' that's even more dangerous. You can't have in the back of your mind the fact that you've had a successful record and maybe we should do it that way again. If you try and do that, say, 'Right, Common People was really successful, se let's do a song that sounds quite like it,' you end up with a load of shit. You can't think about what worked last time. For instance, the last record, I wrote all the lyrics just about in two nights. It was just me at my sister's house with a bottle of brandy...

Ray Gun: In two nights?!

Jarvis: Yean. Well, I tried it again, and all I did was fall asleep. I didn't even gel one finished. So even though you might get to the same destination, you have to take different routes. Maybe that's why it took as long to get this record together. There's quite a possibility that it might totally bomb out, I know, but at least it sounds okay to me.

Ray Gun: Is it possible to be a serious pop artist?

Jarvis: Maybe serious pop doesn't exist. I've always hoped it could. And I've always hoped you could get the music to add the sensibility of pop without the pretension of rock.

Ray Gun: That's one of the things Pulp does, I think.

Jarvis: Weil, that's what we aspire to do anyway. You don't want to be pinned down. As soon as people think they know how you're going to react to any given situation, then there's no point in them taking interest in you any more. It's like, why would anybody buy a new Phil Collins album?

Ray Gun: That said, you can re-invent yourself too much.

Jarvis: Oh, yeah, I agree with that. If you fly off too far, say, 'Now we're reggae," or something like that, that's bad. When I listen to people's stuff, I like to be able to see that it's the same person but they're changed. I've been thinking about Leonard Cohen and the change from Songs From A Room to Death of a Ladies Man. He'd gone from the starkest kind of arrangements ever, to this big fucking, not-one-little-tiny-millimetre-of-space, wall of sound. But even though everything's gone wrong, it's a good, maybe a great album. And you could still tell it's Leonard Cohen. And that's what you want, I think. It's kind of like you're following somebody's progress, and that's what life should be like. You do change, don't you?

* * * * *

After the conclusion of the seemingly endless Different Class tour, Pulp underwent another transformation. Russell Senior, Cocker's musical director for almost a dozen years, left the band for the usual personal and musical reasons. His six-string replacement is one Mark Webber, who began his long involvement with Pulp as a fan. Soon Webber was running the Pulp People fan club, eventually becoming tour manager, then live rhythm guitarist to his final destination as lead guitarist. Though a devout minimalist who lists composer La Monte Young as one of his heroes, Webber has added a surprising edge to Pulp's textures. While no one will mistake This Is Hardcore for rock 'n' roll, the album finds Pulp moving away from their trademark mirrorball beats to a more ominous modernity of guitar atmospherics, haunting rhythms, and experimental sound structures. You know, like Radiohead, only better.

And like Radiohead - and Spiritualized, the Verve, Oasis et al - Pulp have expanded their musical paintbox to incorporate the scope of their vision. Oddly, like all the above artists (save Oasis), Pulp have accessed an expansive musical landscape that is somehow very interior, the sounds that swim within their own heads.

DISSOLVE:

INT. HOTEL ROOM. DAY

Ray Gun: The focus has changed considerably. The lyrics are as straightforward and autobiographical as ever, but the overall mood of both words and music appears to be more contemplative and cerebral.

Jarvis: Yeah, I actually imagine it is. For a number of reasons. A lot of Different Class was observation of social situations. And the way things worked out, the only social situations I was in was like, touring and stuff like that. And I never wanted to write about those because it's just not interesting. You know, it's the ultimate crap song, the acoustic "I'm alone in a hotel room" kind of shit.

Ray Gun: Yup. "Staring out this bus window..."

Jarvis: Nobody wants to hear that kind of rubbish.

Ray Gun: I don't know about that, You're in America now. We like that kind of thing here.

Jarvis: (laughs) So I had to go somewhere else. In the end, I think it worked out all right. It was this idea that you have achieved something that you've dreamed of for a long time. You grow up watching films and stuff, of things that you're aspiring to, and then you're there, you know? Suddenly a lot of things fall away. Everybody sustains themselves on fantasies, and there's nothing wrong with that, it's just that if yon ever have the misfortune to have your fantasy come true, then you have to re-assess it all. And often you don't realise that you've got this fantasy in the back of your head - it's just there, 'cause it's gone in at an early age. Suddenly you think, "Why am I dissatisfied with this thing?" What is it within you that means that this still isn't enough? I suppose that's another reason for it being called Hardcore, as in that's the bit that's left when everything else has melted away.

Ray Gun: It's a great word. It'll be interesting to see how misunderstood the title is in America.

Jarvis: Yeah. but it's going to be misunderstood in the UK as well. People will think This Is Hardcore is like, you know, a compilation of banging garage tracks or something like that.

* * * * *

Of course, Cocker happily plays into the conflicted view of himself as an artist torn between superstardom and bedsit introspection. His most overt public statement was the now legendary assault upon the stage at the 1996 Brit Awards. As Michael Jackson ascended Christ-like towards the rafters, an admittedly tipsy Cocker stormed his way from his champagne-laden table into the footlights, where he proceeded to wag his bum at the bewildered industry crowd. The evening culminated with Our Jarvis cooling his heels in the clink, the tabloids screaming Jacko's allegation that the Pulp frontman had somehow attacked the flock of children used by the King of Pop as living, breathing stage props.

Media madness on both sides of the Atlantic followed, though Jarvis quickly managed to get the truth out: there were no children harmed and no charges filed. In Britain, he wound up a kind of nationalist figure, attacking Jacko's US-born pop imperialism. But the event ultimately served to make Cocker famous for something other than his music. Just like that, he'd gone from the "'Common People' guy to a performance terrorist" in the mainstream's ever-patronising eyes. Like the Different Class song says, "Something Changed..."

CUT TO:

INT. HOTEL ROOM. DAY

The phone rings. Jarvis goes to the bedroom and answers it, speaking softly, complaining about the stomach flu he may or may not have kicked. Ever polite, he explains that he is in the midst of an interview and hangs up.

Ray Gun: After the Michael Jackson affair, there's a sense that now you're expected to be controversial.

Jarvis: Yes. Yeah.

Ray Gun: Which is a thoroughly different pressure than just the pressure of having to follow up a pop hit.

Jarvis: Yeah, I know, that's a pitfall that I wouldn't want to fall into.

Ray Gun: You can become a clown if you do something else.

Jarvis: Oh, yeah; and that's it. For instance. we went on "TFI Friday" with Chris Evans. We went on there to play Help The Aged and he wanted to do an interview with me. Well, you know those life-size cut-outs of me that we sent out on the last record? There's one on the set of that show every week. It gets dressed with different things, and I didn't want that, because I really hate what that programme's become, it's really just an ego exercise for Evans. And it's just not funny! I didn't want to have my cut-out being associated with a load of crap. So I decided that I was going to go on and chuck if out of the window. But I was kind of put off about it, because then it's like, "Oh yeah, every time he's on something he has to do something controversial" But then I thought, "Well, it's a picture of me, so if anybody's likely to throw if out, it's me." So I did chuck it out. It was quite funny actually, because the drummer from Metallica was having a cigarette directly below the window. Luckily I saw him, because this thing was mounted on hardboard, you know, so if it had hit him...

Ray Gun: You almost killed Lars?

Jarvis: I could have done, yeah.

Ray Gun: Now that would have been controversial.

Jarvis: Yeah. I just said, "Look out below," and he moved and I dropped it. I didn't see him afterwards so I could say, "Sorry for nearly killing you." Maybe you can give that message to him.

Ray Gun: lf you had hit Lars with it, it would have been perceived as if you were making this grand statement about the evils of heavy metal.

Jarvis: Yeah, it was very Spinal Tap.

Ray Gun: How did the audience react? Did they react as if it was a bit?

Jarvis: Weil, it was quite good, 'cause Chris Evans was a bit lost for words, he didn't really seem to know what to say. I was considering laying into him, but I thought, "That's enough controversy for one night." I don't want to be known as Mr. Angry, you know?

* * * * *

Anger is but one of emotions that non through the multi-coloured This Is Hardcore. With it's neo-Mott The Hoople backing choir, album opener The Fear is perhaps the first pop song ever about panic attacks, not to mention the first pop song about fearing audience "sing along." Oft-criticised for similarities to David Bowie, the ironic Party Hard sees Jarvis at his most Bowie-esque, as the band boogie down at the Scary Monsters disco. Elsewhere, Cocker deals with impending middle age (Help The Aged) and, in the delightful Dishes, his desire to find some semblance of normalcy in his spotlit life. In one incredible, inventive leap, Pulp have gone from articulating the hopes and dreams of the middle class teenager to expressing the turbulent emotional whirlpool of a generation weaned on F/X fantasy and Hollywood hocus pocus.

CUT TO:

EXT. NEW YORK CITY, DAY

Outside the hotel, Jarvis, his foxy fur draping his shoulders, gels into a waiting town car with his publicist and the Guy From Ray Gun. The black Lincoln heads downtown on a beautifully sunny winter's day.

CUT TO:

INT. RESTAURANT. DAY

Jarvis and the Guy From Ray Gun chat as they look al the lunch menus at the Screening Boom, a hip bistro-slash-revival cinema in Tribeca, the epicentre of indiefilmdom. The restaurant is designed in faux-old movie house style, with '40s-era jazz playing in the background.

Ray Gun: The lyric that, I'd imagine, will be quoted ad infinitum is from Dishes: "l am not Jesus, though I have the same initials."

Jarvis: Well, that one came to me on the bike on the way to the rehearsal room. I often have ideas on the bike. It was about this conversation I'd had at about four o'clock in the morning once with finis bloke who was saying that I was due for a mid-life crisis at 33, because that was the age that Jesus died. So all men are supposed to get to 33, and then measure their achievements against Jesus's and obviously, you find yourself slightly second best. So I was thinking about the way that when you're younger, yon think the world revolves around you, and then thinking, "Weil, maybe if doesn't." There might even have been a bit of the Michael Jackson thing in there as well, 'cause he was setting himself up as that. And do you want to get crucified at the end of the day? Sounds too painful to me.

Ray Gun: Help The Aged also reflects on your awareness of your increasing maturity?

Jarvis: I'm afraid so, yeah. Instead of hiding from these things which, especially in the entertainment business, say that attractive things are youthful things. People are putting off accepting responsibilities and stopping doing adolescent things 'til later. Maybe because there didn't seem to be anything that appealing about maturity. So I was thinking, "We've got to try and find something good in it." Maybe we can invent a new kind of social group or something.

Ray Gun: This is the first time, I think, that people of our age have tried to retain their involvement in this kind of grown-up youth culture,

Jarvis: Right. We're not going to go off and start playing Phil Collins albums.

Ray Gun: Musically speaking, the record appears to have been influenced by soundtracks. Is Love Scenes subtitled 'Seductive Barry' as homage to John Barry?

Jarvis: No, no. That's actually the original title of that song, When we write a song we always give them titles, because the lyrics are always the last thing to happen, so we have working titles to refer to things and they're usually stupid. Hardcore was called 'Barry.' Barry was a big character on this record. One song was Barry Swings. And then we had Seductive Barry." We could have called the record This is Barry...

Ray Gun: Neneh Cherry sings that with you. How'd that come about?

Jarvis: We've done those kind of long flowing semi-improvised songs and I didn't want to just repeat things, so I thought "What would be different?" Instead of me talking to the woman or addressing her, what if she was actually there, as well? I had to think of somebody who was appropriate because l didn't want it to be - I like Serge Gainsbourg with Je t'aime, it's very much, "I'm the master of this situation and you just pant, because I'm turning you on so much." So it needed to be someone that wasn't perceived as a kind of compliant, docile woman, do you know what I mean? So we asked her, and she said she'd do it. I was really pleased.

* * * * *

Love Scenes

(Seductive Barry), along with the record's title track, (which finds Jarvis

directing a real life fuck scene, complete with ecstatic money shot), are the

album's most overt reflections of Cocker's fascination with the cinema. While

recording This Is Hardcore, Pulp found themselves contributing songs to a

couple of screen projects. They wrote Like A Friend with Patrick Doyle,

official composer to the court of Kenneth Branagh, for director Alphonso

Cuaron's remake/remodel of Great Expectations. Pulp also recorded a theme

song for Tomorrow Never Dies, that upon being rejected by the James Bond

people, was renamed Tomorrow Never Lies and placed on the B-side of

Help The Aged. Though that 007 experience was a wash, the band succeed in

placing a lush cover of All Time High on composer David Arnold's

Shaken And Stirred Bond tribute. September of '98 will see their cover of

We Are The Boyz appearing on the soundtrack to Todd Haynes' nostalgic glam

fantasy, Velvet Goldmine.

Conscious or otherwise, the power of the picture show has permeated this former

film student's work. For example, the videos for Help The Aged and

This Is Hardcore point to cinematic touchstones such as Michael Powell and

Emeric Pressburger's A Matter Of Life and Death and the Technicolor

melodramatics of Douglas Sirk. This Is Hardcore sees Jarvis trying better

to understand the difference between the trials of life and mere tricks of the

light. Using chiaroscuro musical textures, easily storyboarded subjects and

structures, even dialogue, the songwriter dissects how the movies' version of

reality has distorted his (and his generation's) worldview to the point of

distraction.

DISSOLVE:

INT. RESTAURANT. DAY

The Waiter sets matching plates of burgers and fries on the table between Jarvis and his inquisitor.

Ray Gun: Cinema and its effect on us seems In be your central theme on This Is Hardcore.

Jarvis: It's like when I first started going out with girls and stuff, and finding it very hard to express myself, because anything you said sounded like a line from a film. Films and TV give you an impression of knowing something about the world or knowing something about situations. But they only show them, they don't communicate what they're actually like, They're no substitute for actually doing it. That leaves you feeling kind of prematurely jaded and a bit jaundiced about things. So when it came to making this record, suddenly it was a bit like The Purple Rose of Cairo, where the audience becomes part of the film. All my life I've been an observer, not only of films and TV, but of life, and then as soon you get that germ of public acceptance, then you are somebody else's show. You're actually part of the action on the screen.

Ray Gun: Right. You've become the shadows and light.

Jarvis: That's why there's a bit of an obsession with it in the record. It's comparing what it was like as a spectator to what it's like being part of the action, and that's always going to be a bit of a disappointment.

Ray Gun: Tell me about TV Movie.

Jarvis: You can always spot a TV movie when it's coming on the telly just by the titles. I don't know how they do it. It must be some process.

Ray Gun: The best one of late is a Tori Spelling movie called Mother, May I Sleep With Danger.

Jarvis: That's a good title. That's a very good title.

Ray Gun: But it's always, like, Touched By Murder: The So-And-So Story.

Jarvis: When I was an adolescent growing up, my main introduction to seeing naked women and stuff was on the TV, If you got a foreign art film on BBC2, after 11 o'clock, you could be probably guaranteed of seeing something -

Ray Gun: What, like bare breasts?

Jarvis: - which was very educational. Oh, yes! Sometimes a lot more than that.

Ray Gun: What a strange country you live in.

Jarvis: I know. You don't get that here... Right, so as soon as you saw that it was a TV movie, I would just turn it off.

Ray Gun: Because you knew there was no nudity.

Jarvis: I knew there wasn't going to be anything like that. So the song is like your life turned into a TV movie, with just some kind of plot for the sake of it and cardboard characters and nothing connecting. Just the kind of thing that fills in time on a TV station.

Ray Gun: Do you want to make films?

Jarvis: Yeah, that's what I want to do. That's why I'm pleased about doing this outsider thing that we're doing,

Ray Gun: Do you only want to do documentaries, though? I mean, that's pretty much what you've done so far. Have you written a screenplay, you know, like Bono?

Jarvis: Has he written one?

Ray Gun: Wim Wenders is directing it even as we speak.

Jarvis: Yeah?!

Ray Gun: Jim Sheridan was originally supposed to direct it. It's called Billion Dollar Hotel.

Jarvis: Well, I didn't know that! I'll reserve judgement on that. But to answer your question: I don't know I think documentary's a good thing to start with, because your material's there. You've still got a lot of options in how you film that material, and how you go about dealing with people to get the best out of them, and then you can play around with the editing and stuff like that. Eventually, yeah. I'd love to do a feature film, but I can't see that happening for quite a while. I wouldn't like to do it until I thought that I could really pull it off. We're trying to produce this 45-minute TV special for when the album comes out, which would be based around maybe five songs from the record, but then there's going to be interludes, some kind of scripted things that are filmed, and then things that already exist from filmmakers that we like.

Ray Gun: Cool! It'll be like The Song Remains The Same. You know, we'll go to your castle...

Jarvis: No, no! We wouldn't do that. (laughs) We'd never do something I like that.

* * * * *

Though Different Class didn't make Cocker and Pulp famous in the States. they have been blessed with a loyal Yank cult audience and the critical appreciation of our often xenophobic rock press, both of whom know a star when they see one. Hey, they're on the cover, aren't they? Whether This Is Hardcore can break them in the Colonies is questionable: Pulp have never been especially easy to grasp and the album lacks the requisite "Wooo-hooo!" radio hit needed for a Brit band to cross over. Still, seeing how the album touches on the subjects closest to the American heart - the price of fame, the illusion of dreams and the impact of worshipping false idols - it might well carve itself a piece of the market. Whether or not if does, this was his dream, right? How was he to know if wouldn't make him happy?

CUT TO:

INT. RESTAURANT DAY

Jarvis and the interviewer sit in the forest green leather booth, their half-eaten burgers in front of them. The interviewer, predictably, is smoking.

Ray Gun: Fame changed everything, and that's become the subject. When most artists go there, they tend to spew Eddie Vedder, I'm-so-miserable-with-my-million-dollars whining.

Jarvis: I know, I know, I know. That's why I have to find some way of expressing it that could relate to the things that everybody feels. It's a modern affliction to feel this vague sense of dissatisfaction and of missing out, of thinking somebody else is having a better time than you are. Because you're always presented with people, you know, the Martini Generation people hanging out with great-looking women all the time. The thing is, these things that you're aspiring to never existed. They had a stylist in and suddenly you've got the light in your eye, and then maybe somebody even paint-boxed it afterwards to get rid of any blemishes or imperfections.

Ray Gun: The problem is, I think, that in order to convey that sort of downbeat dissolute emotion convincingly, you have to leaven if with humour, like Nick Cave, say.

Jarvis: Oh, he is funny, isn't he? He played at the LaMonte Young benefit we did. He wasn't funny. He was really good, but he didn't look very well.

Ray Gun: He was still mourning Michael Hutchence.

Jarvis: Ah, l'Il bet he was! They were really quite big friends, weren't they?

Ray Gun: I can't figure that one, I just can't see the two of them hanging out together.

Jarvis: Well, I met Michael a couple of times, and I'm not an INXS fan or anything, but he was quite a nice bloke!

Ray Gun: And why not? What did he have to complain about? Quite a bit as it turns out.

Jarvis: Well, yeah. Maybe people are beginning to realise that that kind of envy or aspiring to that kind of thing maybe isn't such a great thing, 'cause it doesn't really seem to make those people happy, does it?

Ray Gun: Maybe all this ennui and disenchantment stems from what they call "millencholia," you know, the end of the century blues.

Jarvis: That could be. It's like a pressure cooker atmosphere, that there's not that much time left and everybody's trying to get the last word in. Which I think leads to better stuff being produced, because you've got a deadline now and if you're going to say something about your century, then you better get your two cents down now. If you miss the deadline, it's not really worth saying.

CUT TO:

EXT. HOTEL. DAY

Jarvis emerges from the revolving doors, his fur upon his shoulders, a plastic Duane Reade bag filled with a change of clothes for yet another shoot. He is, of course, the very picture of piss elegant stardom. He shakes his interviewer's hand as he slips into the waiting town car. The interviewer watches, a cigarette between his lips, as the black Lincoln whisks Jarvis Cocker away, off to become shadow and light one more time...

FADE TO BLACK