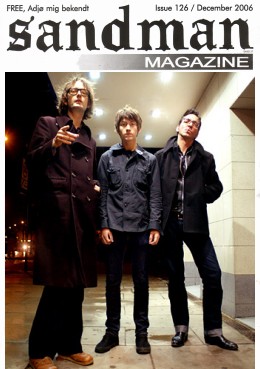

Jarvis, Alex & Richard

Jarvis, Alex & RichardIt's been a good year to be a band from Sheffield. The explosive success of the Arctic Monkeys and Richard Hawley's slowburning but expanding presence on the national consciousness have pulled attention towards the City. When both were nominated for the Mercury Music Prize Sandman thought it'd be good to do a double header with them. Then somebody suggested Jarvis might be up for it too.

Despite having originally left Sheffield in 1988 there aren't many people more entwined in the notion of Sheffield than Cocker. His new solo album was forged in Sheffield, using the skills of Hawley and a ranch of Sheffield musicians and is the return of a much missed voice; acerbic, funny, able to nail common, shared thoughts and feelings in a way which lodges in the brain. Sandman said yes please, thank you very much.

Hawley, 39, and Cocker, 43, old mates, come from a proud City which was almost beaten into submission in the 1980s by economic measures designed to fragment traditional, strong working class communities. In the first interview Sandman ever did, Richard Hawley said, "kids are great for optimism," and Alex Turner, 21, and his crew, seem to represent that new optimism, that sense that the city's talent now has an outlet.

Sheffield, in one form or another, is inherent in their work, in a way that just isn't possible for people from a new place like Milton Keynes or somewhere as diffuse like London. We convene in a café which also serves a labyrinthine set of rehearsal studios; Quantic Soul Orchestra and The Rifles seem to be in that day. Earlier we'd spotted Alex heading the other way by the Arctic's logo stencilled on the flight case of the guitar he was carrying, just another slim young musician heading to a studio, except this one has set fire to the conventions of a moribund music industry. Jarvis and Hawley are late, having put in an appearance on the BBC's Culture Show; they spill out of a taxi; a loud 'Nah then, kid!' from Hawley.

There's something slightly elfin about Alex: his face, with its pointed chin is dominated by large, alert, brown eyes. Jarvis Cocker looks, inevitably, like Jarvis Cocker, he looks remarkably familiar to someone who's never actually met him, his long, spatulate fingers flicker as he speaks. Hawley, in comparison to Jarvis' delicate, ascetic frame, looks like a bruiser. Look out for Pete McKee's pictures, his quaffed up 50s Ted, always leaning with a fag hung from a lip is a ringer for Hawley. When listening back to the tape, you've got a bloke from Pitsmoor, one from Intake and another from High Green. Different accents from the same city but all unmistakeably Sheffield. It's all very unstarry.

Sandman: Have you ever met each other before?

Jarvis: Briefly, it was at the NME awards wasn't it?

You looked quite surprised when Jarvis presented you with the South Bank Show award, did you not expect that?

J: I had to pretend that I was down for another reason, I told him I was there 'cos Melvyn Bragg wanted to meet me.What are these award do's like?

J: You get to meet other people in bands and you can check them off, "knobhead, knobhead, alright, knobhead," but I'm not very good at going up to people just to say "hello."Jarvis, you're doing the London show tomorrow night but there was some talk of a quiet warm-up gig in town?

J: It's just because we were rehearsing in Sheffield, and it was one of those over optimistic things that you think, just because we've done three days of rehearsal...Apparently you've learned to play piano for the album?

J: The reason I had the piano was cos I'd hired one for me kids to learn but neither of them showed any interest and I thought I'm not bloody paying 55 Euros a month for nothing so I ended up playing it.

The album was recorded completely in Sheffield. Were you not tempted to get in a load of sessions musicians and nob off to Guatemala or whatever?

J: It was recorded partly at Yellow Arch and partly at what used to be Axis studios. It's mainly because of Hawley, because he's got about 200 guitars, it'd have been a right nightmare, we'd have had to get an articulated truck to take them all to Paris or London.

A: Are they in a room, all chained up?

J: Yeah he'd have been like Jacob Marley, just clanking away.

How's it been doing a solo album, less democratic?

J: I've never been democratic at all, I've always been a twat, haven't I?That savage humour, Hawley believes, is something integral to Sheffield. His Dad's first job was to bring buckets of beer to the steel workers to keep them hydrated as they forged steel. Looking through the doors of the foundry was like 'looking into hell' as the sparks bounced off the leathery skin of the workers and a strong, black sense of humour was a vital part of keeping everyone going. 'You've got to have humour to get through things haven't you', he says. A recent review of Jarvis' album described him, albeit, affectionately, as a 'misanthrope' while Noel Gallagher ('he's a fine one to talk' sniff both Hawley and Jarvis) reckons the Arctics are young, grumpy old men. Both seem to miss the point. Jarvis talks about the idea of trying to make 'something beautiful' out of something ordinary, some people only seem to see the ordinary and mistake it for complaint.

What was that about on your website when you posted something about getting a Gold record for Coles Corner but took it down again because you felt embarrassed?

H: Yeah, I was embarrassed, but when it happened I was chuffed to fuck because I knew I could give my Dad a gold record. I'm not that bothered myself but I knew he'd cherish it, he's such a massive part of why I'm involved in music. But it felt like I was bragging. I just thought, 'you fucking tool'. I've spent the last 39 years trying to be one of the lads and not be a cunt. I think if you become remote or distant because you think you're better than everybody else then that would upset me more than anything else.

What about you, when it all went daft?

A: I dunno, it was when that tune went number one. That seemed so ridiculous. We do go out but we keep us heads down.

H: I tell you, I sat at home watching telly when Pulp headlined Glastonbury in '95, I was on holiday and my baby was asleep, I was roaring my eyes out because at that time nobody from Sheffield was doing fuck all. It was a moment, y'know, Go On Lads! Alex, you must know most of Sheffield is rooting for you in exactly the same way. That's what I love about Sheffield now. It used to be, and always will be, a little bit, 'cos it's a Northern town, people with their arms folded at the end of the dancehall in the Leadmill going 'go on then, my band's better than yours.'

J: There was nothing in Sheffield then, there were some fanzines at the end of the 70s but they all fizzled out and then there was fuck all.

H: I think that went hand in hand with what was happening politically in the country. Sheffield used to be this Socialist capital of Britain, then all of a sudden Thatcher got involved and everybody, gradually, was taught to be selfish. They'd do that to us by fear, making us afraid of poverty. It was a subtle invasion. There was a strength in the City before that, that was unshakeable and was slowly eroded, well not slowly, it was fucking sledge hammered, and I think that affected the whole generation. It's all about solidarity. They'd taken away that basic working class solidarity, 'you think you can make us do what you want, but all we have to is stand together and you can't make us do owt'. Once they smashed the miners and steel, that were it. I think people stopped believing that. I wish people would realise how much power they've actually got. But how much power does anybody actually want working in a call centre?

Are you much aware of what's going on in Sheffield at the moment?

A: Gas Club, they've got some good songs.

J: I've not seen any bands playing in Sheffield for years, I left in 1988. I did this Observer Music Monthly thing [Jarvis edited an edition last month and organised guest writers including Hawley interviewing Lee Hazlewood] and Russell [Senior] who used to be in the band went out and did a Friday night in Sheffield and he said venues were now advertising for bands, as if there almost not enough bands to go round which it the opposite of what is was it were when I was there.

For bands at the moment it seems there's an opportunity available to them, a door's opened but it might not last long?

H: I disagree. I think Sheffield has now been put on the map forever. Like Liverpool and Manchester, it's a city where there is a guaranteed source of talent. As long as musicians in City believe that and don't get the passion hammered out of them like's happened in the past. Clock DVA is a great example, that first album of theirs has got to be the best Sheffield album, no offence to anybody. That album is the bollocks; it was out there, right extreme, especially at the time it was made. It's called First, especially a track called 4 Hours, you'd love it, Alex, it's very important.

Jarvis, you took a bit of a break from song writing at one point, how was it when you started again?

J: Me? Yes I did. Analysing your own song writing is a bit weird but I did think about it when I came to this record because I thought maybe I'm not going to do another one so, with starting again, I was thinking what am I good at then? So you start writing songs again and the first ones I wrote were a bit vague, like Don't Let Him Waste Your Time and Heavy Weather, they're not so specific and then I 'found my voice' or whatever, seemed to come round to doing what I can do and other people can't do. I don't know how the other guys do their song writing but I'm not really one of them who can sit there and play guitar and come up with something. A little phrase or a tune will come into my head and if it's still there a day later I'll stick it on a tape recorder.With lyrics do you tend to take notes?

J: Yeah, I've usually got a notebook with me just in case.The Sugababes cover of Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor is brought up, it debuted publicly at the NME awards show, Alex looks distinctly bemused.

A: Oh man, when that come on... (He looks skywards but won't comment)

Do they not have to ask you permission to cover it?

J: No. As long as they don't change the words. I had it with that William Shatner thing [a cover of Common People]. I don't actually mind that cover version because Star Trek I used to watch a right lot when I was a kid so it's an honour, but then it gets to the chorus and then Joe Jackson appears out of nowhere and then a children's choir comes on near the end and it gets a bit daft. But I knew nothing until someone sent me an e-mail and said I must go and check out this link.

A: We fancy Bang To Rights [from Hawley's first mini-album]; I thought it'd be courteous to mention it.

H: That's very respectful, have you worked the chords out yet?

A: Yeah, think so, is it G, Em...?

H: Then back round again, that's it.

Alex, you lot seemed to have steered clear of all the celebrity, haven't done all the interviews. Is it a deliberate plan or just that you don't like doing them?

A: That's it. Simple as that, like. The way it's worked for us is that we haven't had to do that. There's no feeling of mystique.Alex has to head back off to the studio. Before he goes he arranges to come to Jarvis' show the next night.

H: It's a brilliant story int'it? And to meet 'em they're sound as fuck. With downloads it's that thing of an artefact against something that doesn't exist, why are record companies so paranoid?

J: It's only if your album is crap that people aren't going to buy it, if they hear it before and think, 'hmm, he's lost it. If it's any good they'll go and buy it.'

H: It's the modern equivalent of the record booths in the 50s. You'd take about 20 records into the booth and you'd buy the one you liked.

On a wall near the café is a piece of graffiti: Myspace is for losers. While the web company's willingness to take credit for the Arctic's success is questionable - the initial free downloads of the early demos were from fan sites and chat forums, like The Libertines - the ubiquity of myspace is unquestionable. Being established musicians, how does Jarvis see it?

J: I didn't want to get into this guilt of not replying because I used to have that. When Pulp were quite famous we used to get fan mail and I couldn't bring myself to chuck them away. So I never replied to them and had them in a bag under me bed. I felt 'you fucking bastard, all these people write to you and you can't even be bothered to write back?' It really did me head in. This binbag was under me bed for years and eventually I burned them. I made a pact with myself so I write a blog every couple of weeks because I think you've got to keep some sort of personal thing going. But it was also really, really handy for me because I'd written that Cunts Are Running The World song and there was no way of getting it out and it was never going to get played anywhere so just putting it on there meant that people could hear it. It got put up on a Sunday afternoon with no publicity or anything and by the end of that day maybe 100 people had been on, three days later it was 1000s and it's had 400,000 now.

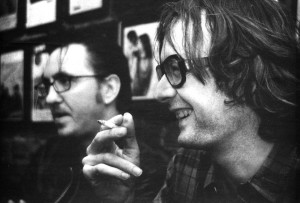

As we head outside to get a last few photos of Jarvis and Hawley, a bloke charges up to Jarvis, grabs his arm, and loudly tells him he's God for 'that Jacko stuff and yer music' as well as introducing him to his baffled Czech girlfriend. It happens really quickly and even though it involved only Jarvis, I found it unsettling, intimidating. What if he'd belted Jarvis? It's a reminder (as is the DJ sticking on a Pulp song when we have a pint in a pub later) that Jarvis' fame went beyond that of music fans. For the record Jarvis treats the fan with a kind of neutral amiability and says he doesn't mind it when it happens. Alex can still go to football matches without attracting attention and Hawley loves the sort of pubs where he can have a pint without being bothered, Jarvis remains something larger.

These are the most visible musical Sheffielders Sandman knows, nice blokes, sane and unpretentious, the tip of a great creative iceberg.