The Geek Can See Clearly Now

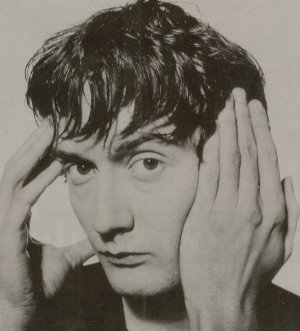

The Geek Can See Clearly NowOn the very night when Prince Charles proudly exited the Ritz with Mrs Parker Bowles on his arm, I went home with Jarvis Cocker. Okay, I admit that I wasn't snapped in the act by a hundred paparazzi. But the entire population of the Top of the Pops bar saw us leave together and I'll bet I was more excited than Camilla. There is something rather illicit about climbing into a black Mercedes at midnight with one of Britain's most celebrated pop stars. And not just a boy-band pop star, but Jarvis Cocker of Pulp, king of cool, geek icon, the man who single-handedly saved a generation of skinny English males from years of body paranoia.

Our meeting was set for 8.30pm at the Top of the Pops studio in Elstree, Hertfordshire, but speeding through the night I discover that the filming is - of course - running behind schedule. Eventually, Cocker takes the stage. Rake thin, he undulates and leaps, singing: "Walk like a panther, fly like an eagle." At 36 he may be 10 (or even 20) years older than the other performers, but his charisma and energy eclipse them all. And, unlike the others, he requires only one take. "Just a quick drink before we leave," he says brightly when he re-emerges. "Wind-down chat, not formal." We adjourn to the bar, where the Top of the Pops posse are knocking back the booze. I keep catching people's eyes. Eventually I realise why - they are all watching Jarvis. "I don't go to pubs now, 'cos I feel on show." He says wistfully.

His fame began in the summer of 1995 when he and his band had a hit with Common People ("I want to sleep with common people like you..."). The scrutiny intensified when, in a protest at Michael Jackson's self-congratulatory show at the 1996 Brit Awards, Cocker stumbled onto the stage and mooned at the 'king of pop'. "Are you coming for supper?" one of his band asks him. "No, I'm heading straight home," says Jarvis, giving me a meaningful look and not telling them who I am. We walk out of the bar together. Am I just flattering myself or is he passing me off as his latest bird?

Once I've got him to myself, I ask whether the age of his colleagues and fans makes him feel too old to carry on for long. "I suppose I'll go on till I feel uncomfortable," he says after one of his rather unsettling trademark pauses. "Pulp haven't got to this point the way you're supposed to, where you start playing music when you are 17 or 18 and you get famous by 20 and you're burnt out by 24. We never had a sniff of the charts until I was in my thirties."

So does he want to be a wrinkly rocker? "No, I most certainly don't." he grimaces. " The thought of being a 45-year-old prancing around on the stage horrifies me, and I hope that if I felt a fool on stage, then I would stop. I do think there should be an age limit on jiggling around - although Mick Jagger is trying to disprove that. Does he ever feel embarrassed when he realises he is old enough to be the father of the girls dancing in front of him? "No", he replies. "Most of the time I can't see 'em. I don't wear me glasses and there's a spotlight shining in me eyes." His accent varies from a neutral London twang to the Sheffield cadences of his childhood.

At the NME awards last week Cocker argued that Labour's champagne socialism had metamorphosed into the even more unattractive "cocaine socialism" - the title of a song on his recent album, This Is Hardcore - so called because of its selfishness. "Sometimes I think new Labour is okay," he says. "Then I heard the other day than Tony Blair had said we are all middle class now, and that horrified me. Being middle class is having two Sunday newspapers in your house and a Dyson vacuum cleaner. It is a certain materialistic way of furnishing your own coffin as comfortably as possible, a terrible blandness. Nobody should aspire to that."

Is he middle class? Grimly, he concedes that he is "more middle class than he used to be" - joking later that he's "saving up for the Dyson". But despite his success, Cocker seems determined not to regularise his life. It is, he admits, beyond him to wear contact lenses. "You've got to be quite organised about where you sleep, for all the cleaning fluids and stuff," he says. "I did have 'em, but they caused me a lot of trouble. Once, I slept over at someone's house and put them in the lids of some herb jars. The next morning, when I put them in, my eye went so red I had to go to hospital. One of the lids was off the chilli powder jar and I'd got chilli in my eye. Also, I kind of like wearing glasses."

His glasses have become a key part of his nerd-chic, but does he perhaps also hide behind them? "No. You can't hide behind them but you can chose whether you want the world to be in focus or not," he says. "When it all gets a bit too much, you can take your glasses off and the world shrinks down to a 6in radius around you. It all goes a bit blurry, people look more attractive. It's like seeing the world through a soft focus lens." There was a time, though, when Cocker had no need for that comforting blur. Throughout his childhood and adolescence in Sheffield he longed to be a pop star, through long years on the dole, and even while he was at St Martin's School of Art in London studying film he dreamt of being famous as a singer. Was it worth it?

"Nothing is ever what it is cracked up to be," he says. "It's like reading a holiday brochure, deciding on a certain hotel, getting there and finding that the water doesn't work. People construct fantasies - like, if I win the lottery everything in my life will be all right. But it's usually not right, you know." It sounds, I suggest, as if he has reached modern culture's holy grail and found it wanting. He disagrees. "It's so easy to become famous now," he argues. "You don't have to have invented a great boon to help mankind, you just need to look right, have a nice pair of tits - look at Emma Noble."

But I counter, he didn't look right - quite the contrary, he was skinny and pale and started his band so that he might have a chance of getting a girl. He was 20 when he lost his virginity. "That's true," he concedes. "I got famous the hard way. You know, you can take a helicopter to the top of Mount Everest, or you can climb it. The problem is, once you have climbed the highest mountain, there's no other mountain left." Nobody could accuse Cocker of not sampling the pleasures of fame. He went to so many showbiz parties that he ended up top of The Sun's "liggers" league. Eventually he tired of it. "It''s lazy, it's easy just to go with what's laid on." Did the celebrity circuit become its own rat run? "Yeah. You are a VIP with a grey ticket, or a pink ticket, or maybe a silver ticket, which means you go to the top room, where you sit with five other people with nothing to say to each other. You have to find another aim."

What is he aiming for now? "That's a good question," he says. Long pause. "My aim is to be a reasonable human being. Before, I was so intent on making it that I belittled the importance of certain things." What things? "I'll sound really sentimental - but quite small things, you know." Like family, I suggest. Cocker was brought up by his mother - "the nearest Sheffield gets to a bohemian" - as his father, a musician, vanished to Australia when he was seven. "Yeah, yeah. They're not bad." Or his new house in Hoxton, east London? "Yeah, houses are okay now. I resisted buying one for seven years because I thought that being a homeowner condemned you to a life of Batchelor's Savoury Rice." What about love? "Always a boon," he quips. Any love at the moment? "Looking, always looking." A girlfriend? "I couldn't say I really have one, no" he replies. Does that mean he has several? "No, no, not that. I just couldn't say that I had an official one. It's easy to meet girls but it is much harder to find girls who don't want to find you in the first place."

Cocker's latest project is certainly a departure from girls, pop and parties. He has spent the past few months travelling the world making a channel 4 documentary called 'Journeys Into The Outside' about people who devote their lives to creating art - by covering their houses in mosaics, for instance. - "without wanting to be celebrated or fated in any way". They are the antithesis, perhaps, of what he has been. "It sounds like something your grandma might say, but I've learnt - or that I'm trying to teach myself - that it is the actual doing of something which is important, the process that is the interesting thing. Not the ultimate destination."

About time, too.