Words: Jonny Beardsall, Photographer: Louise Bobbé

Taken from Telegraph Magazine, 25 May 2002

From Sheffield to London, Jarvis Cocker has always been something of an urban legend. So how come he's started singing about birds and trees, and decided the best place to play gigs is a forest clearing? Is Pulp's frontman a tree-hugger in disguise?

I'm a country boy. As a rule I have never been drawn to cities, but coming from the North, I know Sheffield, vaguely. From the steps of the Crucible Theatre, I can see the Roxy, formerly the Top Rank where I saw the Stranglers in 1977, Silver Jubilee year. "Yeah, I saw them there too," says Jarvis Cocker in his south Yorkshire guttural. I glow. I feel cool and old at the same time.

Unlikely as it sounds, Jarvis and I are going for a walk. Right now, we are trying not to get run over, looking for a break in the humming traffic as we cross Arundel Gate, one of the busiest roads in the city. He doesn't so much walk as lope. He covers the ground like a giraffe, taking long purposeful strides. From the raised eyebrows, grins and sideways glances he draws from drivers and pedestrians, I sense that he is often clocked on his home turf where, 23 years ago, he formed Pulp.

I became a Pulp fan in 1995 when they released the mega-hit single Common People from their fifth album, Different Class. I also bought the dark and scary follow-up, This Is Hardcore, but it is their most recent album, We Love Life, that begs the most questions. The songs empathise with the natural world - animals, birds, grass, trees, weeds, sunrises - and, as usual, Cocker's love affairs. I wanted to know what has got into the mercurial Jarvis. Considering only a few years ago he was writing about being 'sorted out for Es and wizz', I felt the lush woodland metaphors needed an explanation. Why does Jarvis now sound as if he's itching to get his knees dirty? Has he become a tree-hugger? Does he like gardening? Will he be buying a pile in the country?

A walk in the sticks, I thought, might shed some light. It might help explain why Pulp have chosen to play this summer's gigs in Forestry Commission clearings; why their record sales - in conjunction with Future Forests, an environmental group that plants trees to offset carbon dioxide emissions - are funding the planting of an entire new forest of native trees in the north-east; and why Jarvis feels that the time is right for him to connect with nature after more than a decade living in London.

When I meet him, I'm slightly disappointed with his choice of walking wear. Given his obsession with retro clothing (his mum sent him to infant school in lederhosen), I expected him to turn up in something nostalgic, possibly a handknitted bobble hat circa 1932. Instead he looks like an unreconstructed pop star. Tall and whippet-thin, he's wearing a grey corduroy jacket - picked up in a second-hand shop in Sweden - a thin roll-neck sweater and black brushed-cotton flares.

He claims to own a pair of old walking boots but they are in his much-loved, temporarily disabled Toyota that features in the artwork on We Love Life, which explains why he is wearing Kickers. "They're new. The company sent them to me, actually. They just thought I'd like 'em and they were right." He looks younger than 38. As pale as the dead, there is no colour in his delicate features shaded by a tousled wedge of dark hair. I hope it doesn't rain because he hasn't brought a mac.

The choice of walk was his. It was to be a journey through his boyhood, taking in some of the sights, sounds and places that he evokes in Wickerman, a track on the album. Jarvis frowns then nimbly vaults a barrier into the road and, hugging the railing, walks with the traffic as cars pass dangerously close. If he distracts an admirer at the wheel, this could become a tragic news story.

Safe on a pavement again, he points out the half-demolished Sheaf Market. As a teenager, he worked part-time in the fish market near here. "It was a plan by my mother to toughen me up. It worked. If you walk around smelling of fish, everyone takes the piss out of you," he says as we cross the slow-moving Don at Lady's Bridge. Did you ever swim in it, I ask, fishing for early nature-boy credentials. "Urgh, no. I wouldn't swim in that."

There is a footpath on the south bank. "This is where the walk starts properly," he says, looking slightly relieved. To his surprise, there is even an arched wrought-iron sign marking the beginning of the Five Weirs Walk, a five-mile route which should take us along the banks of the river as far as Meadowhall on the outskirts of Sheffield. But there is soon a hitch; a 6ft-high fence prevents us from taking the walkway that will carry pedestrians under Wicker Viaduct. It is, as yet, unfinished, and extends into thin air beneath the arches.

The walk that Jarvis is trying to recollect, he confesses, "was more of a float" but he swears it was possible to walk the bank in several sections. He was in his early 20s when he and a girlfriend launched an Avon inflatable boat and drifted downstream. Now he tells me. Had I known, I could have brought mine and we would now be paddling instead of walking.

Jarvis leans over the bank's chainlink fence and disturbs a pair of birds. OK, so what are they, I quiz. Jarvis smiles and needs no time to answer. "That's a mallard - I can do a mallard - and a Canada goose," he shrugs, with confidence. The bank is skirted with scuzzy washed-up plastics soon to be lost amid the advancing dock leaves and cow parsley. "It's not so nice but the river itself doesn't look that dirty, does it?" he assesses. "I was always fascinated by this part of town." He gestures to the far bank and the Royal Victoria Hotel, or Holiday Inn as it is now also known. "I was always told they found lots of silver cutlery in this part of the river. I think staff couldn't be arsed to do the washing-up and would just lob it out the windows."

When he left home at the age of 18 he shared a 'very bohemian' caretaker's flat in the old Capital Steel Works in Sheldon Row, a now-demolished building a stone's throw away. Before that he had lived with his mother and sister in Intake, an insalubrious district on the outskirts of the city. However, despite the fact that Jarvis's songwriting is preoccupied with class and background, his family were not 'common people', certainly not by northern standards - they even had holidays in Ibiza and Majorca. They lived next door to his maternal grandparents (his grandfather was a joiner-undertaker and also ran a DIY shop).

"My grandparents' house was quite grand, actually. It was the sort of manor house in the area before other houses were built. We lived in what had been the stables or something next door which had an orchard in the back garden." His grandmother, now 86, lives with his mother in Nottinghamshire. "She's like all grandmas; she says I don't shave often enough 'n' stuff," he says as we try to pick up the path further along the river bank.

Moments later, with the route still evading us, a motorist recognises Jarvis, pulls over, leaps out and asks for his autograph. Jarvis scribbles in the delighted man's chequebook. 'What are you doing here?' the man asks. I wonder too. I need this stranger. To be precise, I need his car. 'Get in, Jarvis,' I urge. I ask the driver, a marketing director who does not look like a kidnapper, to whiz us back into town as walking much further looks futile. He agrees and, with the pop star in the front seat, we've made his day.

I turn off the tape-recorder and think, 'Lordy, what to do next?' And then I think of Stanage Edge, the four miles of gritstone crags 20 minutes' drive away in the Derbyshire Dales. It's arrestingly beautiful countryside. If there's a genuinely rustic Jarvis waiting to burst forth, this is where I'll find him. "Yeah, I like it there, been there many times," he says. Phew.

Jarvis is a sensible grown-up with a driver's licence so, this being his neck of the woods, I suggest he drives me. Although he would rather use his beaten-up bicycle or the Tube than drive when in London, his hired Fiat is soon nosing into swirling afternoon traffic and heading east for the hills. I can't boast about my own driving, but Jarvis's style at the wheel is idiosyncratic; at 6ft 4in, he crouches low over the dashboard with his eyes pressed close to the windscreen, peering through the heavy black frames of his Cutler & Gross specs.

"I had a friend who worked there so I got a discount," he says. "I'm really short-sighted so I have to wear them all the time. I've two identical pairs, just in case I tread on them. I can't see without 'em. I wear contacts on stage because I got fed up with losing my glasses. At one concert in Sheffield I spent 10 minutes looking for them. They'd gone in the bass drum kit. After that, I thought it was high time I got some contacts, it was undermining the performance."

Feeling guilty, I stop distracting him as, mapless, we try to find our way out of a town that has changed beyond all recognition since Jarvis last found his way around it. We go twice round a roundabout, just to be sure. He sounds more certain when he points out the children's hospital where as a five-year-old he had meningitis. "You had to be in isolation. I was in a whole row of glass-walled rooms. You could see other kids but couldn't talk to them. It was quite strange. I'd been to the swimming baths and remember eating a packet of crisps - the ones that had a clear star on the front - and starting to feel really ill." He remembers the needles which 'they stuck in wrong first time so did it twice' and the lie 'you can see mum if you don't cry'. He didn't cry but when he asked they said, 'Oh, your mum's gone home.'

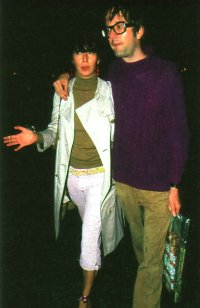

Two years later, when Jarvis was seven, his father left home and emigrated to Australia. It was his mother, a former art student, who held the family together. "Because of my parents' marriage splitting up and other marriages around me going wrong I never thought I'd get married," he says. But it seems he has had a change of heart. In July he is marrying the chic Parisienne, Camille Bidault-Waddington - and they may even settle in France. The lithe 32-year-old stylist is in demand from the likes of Marc Jacobs, Pucci and Emanuel Ungaro.

Two years later, when Jarvis was seven, his father left home and emigrated to Australia. It was his mother, a former art student, who held the family together. "Because of my parents' marriage splitting up and other marriages around me going wrong I never thought I'd get married," he says. But it seems he has had a change of heart. In July he is marrying the chic Parisienne, Camille Bidault-Waddington - and they may even settle in France. The lithe 32-year-old stylist is in demand from the likes of Marc Jacobs, Pucci and Emanuel Ungaro.

The couple first met in 1998 when Camille was styling the sleeve of This Is Hardcore. "There was nothing between us then," he says. Their eyes met again a year later across the floor at Pulp bassist Steve Mackey's birthday party. "More like, our eyes met on the floor," Jarvis sniggers. They have been living together for several months in her rented house in London Fields not far from his own home in Hoxton, east London. And, killingly ironic for a man once gripped by class, Camille appears uber-posh. "Well," he sighs, "it's hard to tell with the French. She does have an English strand to the family - some of them moved to France during the Industrial Revolution."

Does Camille know what she's getting and has he had to adjust his domestic habits?

"Well, you have to know what you're getting, don't you? As for making any changes, well, yes, I bath more." She ought to know about his moths. "They're in my wardrobe," he groans. "I know exactly where they came from as well. I bought this second-hand suit in New Zealand."

Next week, he has to see the doctor, part of the pre-marital rigmarole required by French law. "You've got to have blood tests and stuff - y'know, to make sure you've not got any horrible diseases. It doesn't mean you can't get married if it turns out you've got a horrible disease, it's just so your partner is aware of it. I suppose it's quite sensible, really. They check if you can have kids too. I'm having that bit done on Tuesday. It costs a fortune - it's 90 quid."

So what about children? His betrothed already has a child, six-year-old Otto, from a previous relationship and Jarvis, it is said, is rather good with him. "I've never thought much about kids. Well, you kind of worry you might end up like your father so you shy away. But I hope not. I am far older than my parents were when they had kids."

Gradually, the town gives way to steep valleys, in places flooded with a reservoir and skirted with a patchwork of fields, dry-stone walls and conifer forestry enclosures. It has taken us 45 minutes to reach the little car park below Stanage Edge where half a dozen other cars and an unremarkable ice-cream van are lined up. The last time Jarvis was scampering around up here was on New Year's Day 2000 with his younger sister, Saskia - with whom he is staying in Sheffield tonight. "The whole of the Derwent valley had been full of mist," he says. "It was a poetic sight to see at the beginning of a new century." He pauses, his long, slender, squeaky-clean fingers reaching to answer a bottom-of-the-line Nokia mobile phone in which his management persuaded him to invest. "They were fed up of not getting hold of me," he mutters. Famously frugal, he uses pay-as-you-talk cards. "Well, I'm from south Yorkshire, aren't I?"

As we start to pick our way up the track, he seems more aware of the colour of his socks ("they're blue, they don't match") than the spindly, twisted silver birch ("yeah, I'm pretty rubbish on tree names") that are growing in Stanage Plantation among the boulders. "To expect the trees to tell you things is a bit much, isn't it?" he says, when I ask him about The Trees, a track on We Love Life. He sings about trees being 'useless' which, until he expounds, would not advance his woodland integrity. "In a romantic situation, people carve names on them and stuff, 'cos, I guess, you get some kind of permanence by doing it. But go back five years later and you can't read it 'cos trees don't grow uniformly - you're left with a distorted blob. The idea is, trees keep growing long after a relationship has gone down the pan."

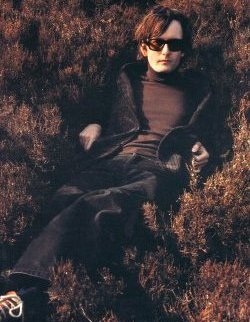

This path takes us out of the trees and on to the edge of the moors. It is sunny but it's an unreasonably nippy spring afternoon and Jarvis is looking underdressed, his charity-shop-chic kit clashing starkly with the garish breathable fabrics worn by others passing this way with maps in plastic cases hung around their necks. But what else would you expect?

"Brrrr... it's a lazy wind... one that can't be bothered so it blows through you," he calls out, matter-of-factly, while he dances about on the rocks trying to keep up. We have reached an obvious turnaround place - a bungalow-size rock - and huddle beneath it for a few minutes. By this time Jarvis has had enough of my countryside quiz. "Rather than building up a catalogue of what's what in the countryside, I'm just building up a feeling for it all. I want to spend more time in places like this; you get a bit of space, not just physically but mentally as well," he says, turning his back to the fresh wind.

His fingers shake and his teeth chatter as he attempts to light a Silk Cut Extra Mild. Trying to be helpful, he remembers that he has successfully grown a cutting he took from a fig tree in Bunhill Fields, the famous cemetery near Hoxton, so I can, at least, assume he has green fingers. The tree he pruned is massive and grows near a stone commemorating William Blake, who is buried somewhere in a pauper's grave. "I snapped a branch off, put it in a glass of water for a few months, then planted it. Now it's about 18 inches - it's the first thing I've grown from scratch," he marvels. "The forest we're planting is at Coatham Wood, near Teesside. I haven't been there but I'd like to."

And he is considering getting a dog. "I'm thinking it would be good if I move to Paris; a good excuse to go walking and explore places. If you see a road and you like the look of it and walk down it, people think you're a burglar but if you've got a dog with you, they think, hmm, he's just exercising his dog."

Had it been wet on our walk, I am not sure how we would be faring. "Yeah, I don't like the modern outdoor gear, I prefer the more traditional look," says Jarvis. He makes a reference to Lindsay Anderson's Seventies film O Lucky Man!, the odyssey of a trainee salesman. In it, there's a sequence where the character is lost on a moor in a gold lamé suit. "It was so inappropriate but it looked really good," says Jarvis.

Out of the wind, he moves from the rock and lolls on his back in a patch of crisp heather. He touches on a Ted Hughes short story, The Rain Horse, in which another man in a suit revisits the countryside where he was brought up. It is raining and, as the man takes shelter, he is worried by a horse. "It attacks him. He's lost touch with the landscape that spawned him. But in the end, he makes a connection again. He chucks a stone at the horse but ends up with his suit all ripped."

Jarvis is not really a suit man, although Vic Reeves once described him as 'the weed in tweed'. He smiles. "I had a suit made by a Sheffield tailor 'cos I'd been to the Outer Hebrides and bought some Harris tweed - it was a holiday. I had another made by Timothy Everest five years ago but I lost it after three weeks."

Come on, how do you lose a suit?

Come on, how do you lose a suit?

"I think I left it at Top of the Pops or something. It cost a fortune an' all. I thought, that's no good."

In hill-walking terms, this has been no extreme hike and just about scrapes in as a stroll, a very gentle ramble. But if we don't get a hot drink, one or both of us may die. We jig-jog down to the car park where the ice-cream seller is still parked up but doing no trade. I rap on the window and we both push wind-blown heads inside. 'Nah, I don't do teas,' he informs, before starting to bob up and down uncontrollably. Star-struck, his face lights up as he stares at the pop star and then addresses me as if Jarvis - inches from his nose - does not speak English. 'It's 'im, i'n't it? It is 'im... erm, y'know, 'im wot sang that... er, that song about, er... something 2000.' Jarvis sighs, then helps him out with a low-volume burst of Disco 2000: "Won't it be strange when we're all fully gro-oh-oh-own... But how about some tea?" No, definitely no tea.

The two accents are similar but Jarvis's is softer. When he first moved to London, he admits his vowels became even broader. This was an affectation. "I over-compensated because I didn't want to change," he explains. "I don't like change. You see, it's considered the ultimate crime in Sheffield to have ideas above your station; it's a real mindset. I quite like it 'cos it does undermine any pretentiousness."

Jarvis Cocker has never been accused of trying to be someone he isn't. On our interrupted schlep, he hasn't pretended he's a frustrated backwoodsman or closet tree-hugger or that he knows too much about nature - unless you count his fig tree - but in his own self-effacing, thoughtful way, he is working on it. Perhaps it will take a chateau in the French countryside. "I dunno about a chateau. I'm now thinking I could live in the country - but I might just like a hut or something," he murmurs.

Two years later, when Jarvis was seven, his father left home and emigrated to Australia. It was his mother, a former art student, who held the family together. "Because of my parents' marriage splitting up and other marriages around me going wrong I never thought I'd get married," he says. But it seems he has had a change of heart. In July he is marrying the chic Parisienne, Camille Bidault-Waddington - and they may even settle in France. The lithe 32-year-old stylist is in demand from the likes of Marc Jacobs, Pucci and Emanuel Ungaro.

Two years later, when Jarvis was seven, his father left home and emigrated to Australia. It was his mother, a former art student, who held the family together. "Because of my parents' marriage splitting up and other marriages around me going wrong I never thought I'd get married," he says. But it seems he has had a change of heart. In July he is marrying the chic Parisienne, Camille Bidault-Waddington - and they may even settle in France. The lithe 32-year-old stylist is in demand from the likes of Marc Jacobs, Pucci and Emanuel Ungaro. Tree Hugger In Disguise

Tree Hugger In Disguise Come on, how do you lose a suit?

Come on, how do you lose a suit?