Cocker Of The North

Cocker Of The NorthJarvis Cocker has been chronicling the ironies and oddities of modern suburban life for 17 years, but only now is his band Pulp reaping the rewards.

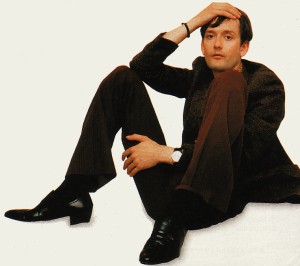

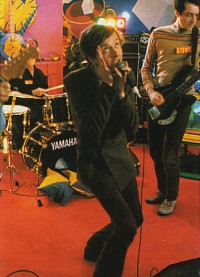

Twitching like a stick insect, Jarvis Cocker, Pulp popster, stalks across Glasgow's Barrowlands stage on the first night of his British tour. If you didn't know better, you might mistake him for an excitable geography teacher in his tweed jacket, burgundy cords, buttoned-up shirt and shiny tie. Six foot four and built like a Twiglet, Jarvis, at the tardy age of 31, cuts an unlikely dash as a teen idol. But a veritable idol he is. The tour sold out weeks ago. Common People, the first single from Pulp's new album, leaped to number two in the charts, followed by the equally successful single featuring Mis-Shapes and Sorted For Es and Wizz.

"Jarvis has sex appeal," says Nicola Logan, a pretty 19-year-old student in the crowd, then checks herself, as if caught fancying the school swot. "Well, charisma... He's not exactly good looking. I like him for his mind, he's really funny." Pop's Mr Sex, as he has been dubbed by some magazines, is characteristically modest. 'Anybody who is perceived to have got some sort of success becomes more attractive. People say that Angus Deayton's attractive which I can't see myself. Phil Collins gets girls, look at the state of him..."

He is just as surprised by the furious tabloid headlines and tut-tutting from the police that greeted the release of Sorted for Es and Wizz. The sleeve included diagrams of how to fold a 'wrap' for concealing amphetamines. 'Ban this sick stunt', demanded the Daily Mirror, accusing the band of offering a 'DIY kids' drugs guide', while Capital Radio threatened not to play it at all.

With the air of a hurt schoolboy unfairly accused, Jarvis painstakingly defends the song. "It's neither a condemnation nor a celebration of drugs. It's just a factual look. It's about a time when I went to a lot of warehouse things. It was completely different to going to a Roxy discotheque in the middle of town, people were so friendly. Then, of course, you realised that it was mainly because they'd taken loads of drugs and you became disillusioned with it."

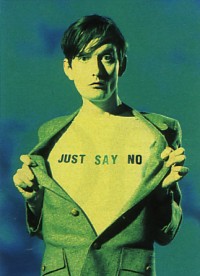

As for the 'wrap' illustrations, they were just a bit of origami, according to Jarvis, "and origami does not lead to drug addiction, as far as I know." The band agreed to remove the offending diagrams, but not without a few sly digs. The day after the explosion, Jarvis appeared on Top of the Pops reading a copy of the Mirror. At the following week's performance he produced an elaborate origami construction for the cameras. Meanwhile, he berated the Mirror in the music press, alongside pictures (presciently taken before the event) showing him po-faced in a Just Say No T-shirt.

On the Barrowlands stage the lights strobe, plunging the band into a swirl of lava lamp bubbles. Jarvis launches into Mis-Shapes, his anthem to nerd youth, a battle-cry to misfits everywhere, rallying us to take on the 'blokes with 'taches in short-sleeved white shirts telling you that you're the weirdo'.

Our champion knows a thing or two about blokes with 'taches. From an early age, growing up in Sheffield, he care fully researched his life as a proto-pop star. "The message that I got was that you were supposed to be an individual and express yourself through music and every other aspect of your life. I used to wear my Dad's Sixties suits, three sizes too big. I dyed a pair of my grandad's shoes turquoise with Lady Esquire shoe dye and had pink laces in them - stuff like that."

This, as Jarvis points out, was not a whimsical undertaking in his part of town. "If you look a bit different they'll think you're queer or something and want to do you physical harm. I've never been really badly beaten up, though I once got a kebab pushed into my face with quite a lot of force on a late-night bus."

Jarvis may have his tongue firmly in cheek as he pouts and poses for the cheering, moustache-free Glasgow crowd, but there is no doubting the sincerity behind the music. It has taken 17 years, from the band's inception during a school economics class, for them to make it. That must count as one of the longest gestations in pop history, reducing Blur, Oasis and the other 'Britpop' bands Pulp are bracketed with to mere blips on the evolutionary scale. All that time Jarvis carved away at his private seam, songs about frustrated housewives, dogs, buses and fumbled sex on nylon sheets; Larkinesque vignettes of life in the Sheffield suburbs.

"I didn't like the lyrics of most pop songs because they painted an idealised world: when I left school and started doing things mentioned in songs, like kissing girls, it didn't measure up, and so I decided to put some realism into my lyrics," he says.

But it is usually a tender version of reality, as in this wistful reflection of first love from Disco 2000, on Pulp's new album: 'You were the first girl at school to get breasts / Martyn said that you were the best / The boys all loved you but I was a mess... / Oh, Deborah, do you recall / I said, 'Let's meet up in the year 2000 / Won't it be strange when we're all fully grown? / Be there 2 o'clock by the fountain down the road' / I never knew you got married.'

In 1981, when Jarvis was still at school, the group had a coveted John Peel session on Radio 1, but not much happened after that. Pulp went through numerous incarnations, releasing several albums to muted interest, but Jarvis stuck it out. Why didn't the records find an audience? "The Eighties had something to do with it," he believes. "The 'I'm all right, Jack' mentality, the emphasis on material things, the surface look of things, the shiny Porsche and the lovely grey leather sofa. It didn't matter about content. In the same way Mike Leigh and Ken Loach were making films through the Eighties but being ignored. People wanted Merchant Ivory and Brideshead Revisited."

A self-confessed "social-security scrounger", he hung about Sheffield, spent a lot of time in bed and filled dull moments scouring charity shops and jumble sales, evolving his inimitable style. "If you've bought something and it only cost 20p you can experiment and throw it away if you don't like it." He is still keen on the charity shop look, but finds he hasn't the time to hunt out the gems these days. Instead he is making do with some clothes sent in by designers. "I've got a meeting with Katharine Hamnett and I've managed to get Gucci to send me some shoes", he grins, pleased with himself. "I do think there are some quite good clothes designers around at the moment."

Jarvis generally sports a suit, teamed, perhaps, with jelly shoes or bright green loafers. He wouldn't dream of slipping into something more comfortable. "I don't own any casual clothes," he says emphatically. "I don't like it when you see somebody in a band who has a reputation for wearing good clothes and then you see them in a tabloid newspaper with a jogging top on." As Nick Banks, Pulp's drummer for nine years, puts it, "Jarvis hasn't changed. He dresses the same wherever he is, only the twitches aren't as bad off stage."

Between songs at Barrowlands, Jarvis chats away to the audience as though we had all dropped in for tea. He mentions the local market: "Unfortunately we got here too late," he sighs. "I could do with a new pair of trousers." To enthusiastic shrieks from the girls in the audience he reels off his hip and waist measurements in case we spot a suitable garment, then declaims, "There's more to life than trousers, but not a great deal more," paraphrasing a Smiths lyric. There is more than a touch of the Morrisseys to Mr. Cocker but you suspect Jarvis can tell better jokes.

Lesser mortals, languishing unnoticed for so long, would surely have given up the rock and roll road years ago. It is not as if he didn't have a choice. The boy did well at school. He was interviewed for a place at Oxford, but came unstuck by pretending to have read a book which he hadn't. He was offered a place at Liverpool to do English, but kept deferring it until they finally stopped asking. "My mum wasn't very pleased," he laughs.

Despite herself, Christine Cocker seems to have contributed to the emergence of the pop star in her son. First she gave him that uncompromising name in a neighbourhood of Shanes and Waynes. Then she decided not to cut his hair, giving him a girlish charm, and, as Jarvis painfully recalls, sent him to school wearing lederhosen (a present from relatives in Germany). "I looked like an extra from Heidi."

He may not have shown it at the time, but he is grateful to her now. "I wasn't a planned pregnancy, she had to give up being at art college to have me. Then my father left when I was seven. She refused to go on supplementary benefit - she had to earn money, so she ended up with a job emptying fruit machines."

He grew up in a very female environment, which perhaps explains why Pulp's lyrics are so often addressed to women, and why at least half the audience tonight are female. "There was my mum, my sister and myself in our house. Next door was my grandma and grandad, and my auntie across the yard - her husband left about the same time as my dad - then my grandma's sister lived across the road. I was the oldest child, and all the other children who came after were girls until my little cousin, who was loads younger than me so I couldn't really play with him."

Cocker Senior was rarely mentioned at home, "Except when I did something bad," says Jarvis. He had disappeared to Australia where he managed to persuade a radio station in Sydney that he was Joe Cocker's brother (untrue) and secured a job as a DJ. "I don't know exactly what he's doing now," says Jarvis. "He had an illness and went on a kind of walkabout in the desert for a while. Now he's moved up to Darwin, which is one of the most remote parts of Australia, and plays in some kind of jazz funk band, part-time."

It is not hard to guess who Jarvis takes after. "I know that because of things his side of the family have said. Just the way I walk and the way I talk, which is weird because I haven't seen him since I was seven." He tells an eerie story of finding his father's picture on an old student ID card. "He was exactly the same age as me when I found the card. He had this little beard on the end of his chin, which is what I'd grown, yet I'd never seen the picture before."

His mother did her best to steer young Jarvis on to a more sober career path, sorting out a Saturday job on a fish stall, for instance. "That was part of her drive to make me sociable," he recalls, 'to get me out of the house because I used to stay in and listen to the radio all the time. Scrubbing crabs was my basic thing.' Alas, it did not have the desired effect on his social life, at least with the opposite sex. "When you're 16 or 17, if you've not got the looks on your side for getting off with girls, and then coupled with that there's a faint tang of fish...'

Jarvis talks constantly in a thick, gentle Sheffield accent, dropping a stream of bizarre anecdotes at every turn. Like the time in 1985 when he fell from a window ledge while trying to impress a girl with a Spiderman act and ended up in hospital for six weeks. Clive Solomon, who signed Pulp to his record label that year, fondly remembers Jarvis continuing to use his wheelchair as a stage prop long after he'd regained the use of his legs.

His songs are full of equally strange little tales. A teenage Jarvis hides in a wardrobe to watch an older girl in her bedroom with a boy; a rich art student wants to sleep with 'common people' and enlists our hapless friend...

Given the dash of Walter Mitty in his blood, it occurs for a minute that he might be making it all up. Jarvis looks affronted. "I embellish things, but the starting point is always true. It's me kind of dramatising my own life. I often get involved in ironic situations. But if people call my music ironic, and by that mean that I'm in some way detached from what I'm writing about, that really irritates me."

In 1988 he finally left Sheffield and, with Pulp's bassist Steve Mackey, took a film course at St Martin's School of Art in London. It was another six years before Pulp had their first real success in 1994 with the album His 'n' Hers, which made it to the Top Ten and was nominated for Mercury Music's album of the year award. Then in June this year came Common People, and suddenly everyone wanted to hear more.

He may have spent only a few months in the limelight, but up on the stage Jarvis holds the audience in the palm of his hand. Leonard Cohen meets John Cleese as he leads us through the odd, endearing, very English world of Pulp, whipping from one fizzing pop melody to the next. It is as though he's been doing it all his life - and in many ways he has.