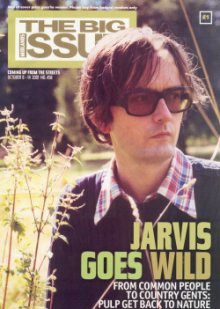

Pastures New: The Big Issue Interview with Jarvis

Pastures New: The Big Issue Interview with Jarvis

Words: Tina Jackson, Photographer: Eva Vermandel and Rankin

Taken from The Big Issue, No. 458, 8-14 October 2001

Pulp's Jarvis Cocker spent his whole life wanting to be famous, and hated it when it finally arrived. Pop's shabbiest superstar tells us how a long walk in the countryside helped get his head together.

The Serpentine Gallery's outdoor cafe in Kensington Gardens is a shambles. Pulp's Jarvis Cocker has only just got his coat off and he's flailing around like a hapless, hyperactive baby giraffe. It's the chairs: they look bleached-linen cool but when you hang your coat of the back, they collapse and Jarvis' jacket goes for a burton. The wind tunnel effect caused by intentional gaps in the cafe's aluminium structure sends it skeetering across the floor. Worse to come. Britain's longest, lankiest pop star folds himself into the traitorous chair and picks up a bottle of orange juice. It cascades into a pulpy puddle on the floor. The two napkins placed by a hopeful Jarvis in the middle of a bright-orange mess only mop up a fraction. All windmilling arms and legs, he goes into a frenzy of cleaning up, grabbing a handful more napkins, stooping to place them carefully into the wetness; stamping firmly on each.

It's his own fault. Pulp's new album is called We Love Life, and it's about nature. So he wanted to meet in a park. This one, with its statue of Peter Pan, is appropriate for Cocker, 38, who was in the band for 15 years before Pulp made it massive in the mid-1990s. When Different Class and its hit single Common People came out, he was in his 30s, a specky, overgrown Northern oddity who wrote some of the best pop songs the country had ever heard. Then he mooned at Michael Jackson at 1996's Brit Awards and at 33, became the common people's hero.

Even in his fourth decade, though, he wasn't old enough to deal with the fame he'd spent his life dreaming of, and working towards. "I didn't want to be famous," he says, owl-like behind huge trademark glasses; the result of childhood meningitis. "People see fame as glamorous. I was quite shy as a kid and I wanted to do something where people would pay me attention without actually having to go out and say, 'Notice me'. It's easy to feel you're insignificant and don't mean anything, and you think being famous will make people pay attention to you."

Pulp weren't just enormously popular, they were hugely cool, too. Jarvis was adopted by the fashion crowd as their personal pin-up. For a while, he dated hip US actress Chloe Sevigny. For someone who'd been defined for most of his adult life as a misfit and an odd-ball, a crooner clad in the Northern-camp glamour of charity-shop chic, it must have been a weird shift in self-perception. "It was a bit difficult and a bit crackers," he offers laconically. He is, obviously, still shy.

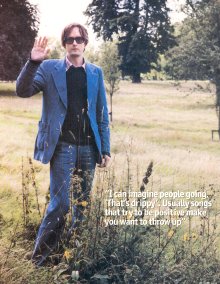

But maybe pop's Peter Pan is growing up. The man who made crimplene and polyester into staples of pop-cultural cool in the 1990s is having, with We Love Life, his pastoral phase. Titles like Weeds, Trees and Sunrise reflect a nature theme running through the record. "I can imagine people going 'That's drippy'," says its creator. Of course it isn't; no one plants a telling image into pop lyrics with such lethal precision as Cocker. We Love Life contains priceless gems. 'We are weeds, vegetation / Dense undergrowth / Through cracks in the pavement / There we shall grow / Places you don't know', he sings on Weeds. "Usually songs that attempt to be positive are horribly sentimental and gooey, make you want to throw up," says Cocker. "So any optimism has been hard-won."

It's a life-affirming, lush concoction after the bleak, burned-out brilliance of The Is Hardcore, which catalogued post-celebrity crash-and-burn. A sense of loss pervaded that album, which referenced hard pornography, hard drug-use and losing the plot. "It's an accurate representation of where we were at, at that time, but you don't want to live your life in that kind of mental state, do you?" says Cocker. Fame wasn't all it was cracked up to be. "It's not all that inspiring. I got very little inspiration from it. But I'm not on Prozac, you know what I mean?" he says. Despite the outfit - possibly the worse flared denim suit on the planet combined with shiny new Kickers and hair that needs a wash - he is adorable: softly-spoken and down-to-earth.

This Is Hardcore came out in 1997, and there's a good reason We Love Life took four years to follow it. "People always want repair-jobs, or escape-jobs to be instant, like joining religious sects, but they can't be. You have to be patient. You take your car in, or your washing machine - and people expect themselves to get fixed that quickly. But you can't." In Cocker's case, too, it was exacerbated by the fact that when you're famous, everything's meant to be perfect. "Most people are fucked-up in some way," he says. "And if you're famous you think, 'Why the hell should I be fucked up'". Bob Lind, on the new album, is explicitly about this particular dilemma.

Back in the real world, though, it's getting better: "I've got more money than I've ever had in my life. I've got no right to moan. And I'm not moaning anymore." A rogue gust of wind blows an empty polystyrene cup off our table. Cocker catches it and adds it to the orange juice/napkin creation at our feet. It's starting to look like an artistic installation. Combining romance and realism We Love Life has some swooning moments. But Jarvis isn't sure if he's a romantic. "If you asked any of my girlfriends they'd say 'No, he's not'. It's something I get criticised for quite a lot. I do avoid being sentimental. But it's dealing with emotions. It's slightly sad because when you write about things, they're dead, but by writing about them, you bring them back to life. It's the nearest thing to a diary that I've got. I don't keep a diary. Maybe I don't need to."

Produced by legendary Scott Walker - the first time the legendary 1960s singer/songwriter has ever produced another act's work - We Love Life's thrillingly warped jaggedly romantic tracks are lush and potent with Pulp's dramatic mixture of beautifully-drawn vignettes, sly social comment and unabashedly personal stories of sex, love and loss. Innocence irrevocably gone, We Love Life is about the triumph of hope over optimism. In places, it's very dark. One song, Weeds, is about asylum-seekers and the underclass. "There are sectors of society that are looked down upon," says Cocker. "Like prostitutes. But they're exploited by others for entertainment. Most vital ideas come from the street, and people further up the food-chain exploit them."

We talk about globalisation and commodification. Cocker wants to point out that when it comes to exploitation, Pulp themselves feel ripped off. "Coca-Cola wanted to use Sunrise (the album's coda) for this TV ad and I guess they expected us to say yes. But I thought, 'It's about some kind of new dawn. Do I want to hear that song and think about Coke?' So I said they couldn't use it. And they got a load of musicians to write a new song which is uncannily similar. But I'm glad we didn't let them have it. It would have been against my beliefs."

What has he been doing with himself between albums? "Trying," he says. "Living in me house. Having weekends away. I haven't done anything spectacular. Staying in one place helps, because we'd been touring a lot and you end up not knowing your friends so well." Like a big teenager, Jarvis likes living with a crowd of mates; two of the people who share his London home went to school with him. "It's a bit of a reality check. People's tell you when you're being a prick. Although you have to find out for yourself." He admits, that yes, in the 1996-97 off-the-rails days, when he was drunk most of the time and practically to be seen at the opening of an envelope, he was a bit much.

"I've been really unreasonable, at certain points, but you don't realise it at the time." He points out that he's not the only one who's lost the plot. "Everyone goes off the rails once or twice. You'd get too bored otherwise." He smiles a mischievous smile, but his next words are more contemplative. "In a way, it can make you a nicer person. You're not so arrogant. You realise you're not so great, you're capable of making mistakes... you're not so fantastic."

"I've been really unreasonable, at certain points, but you don't realise it at the time." He points out that he's not the only one who's lost the plot. "Everyone goes off the rails once or twice. You'd get too bored otherwise." He smiles a mischievous smile, but his next words are more contemplative. "In a way, it can make you a nicer person. You're not so arrogant. You realise you're not so great, you're capable of making mistakes... you're not so fantastic."

That time still obsesses him. But he disliked not being able to live a normal life. "When you go through that sacred portal where you get right famous, it gets hard to go out. I've always hated being stuck in the house, I can't bear it. But I thought, 'I can't go to the pub any more, so I'll go to those parties'. That phase - it was crap." In its aftermath, Pulp still count. "Their popularity isn't what it was at the height of Britpop," comments Face editor Jonny Davis. "But there's not a British lyricist to touch Jarvis. He's what makes Pulp cool."

After Pulp's long years as outsiders, Cocker is "proud that we still stick out like a sore thumb." His interests outside the band are eclectic: he's part of a DJ collective called Desperate (there's a badge pinned on his sweater which says, 'I'm desperate'); he takes part in a variety of odd, arty events, and a couple of years ago, he presented a Channel 4 series on Outsider Artists. But he's not sure the word 'arty' applies to him. "I did go to art college and I do take notice... I'm interested in people expressing themselves, but I find a lot of the time people are desperate to express themselves and haven't got anything interesting to express. The lifestyle's become a cliché. But I do like creativity. I'm not a philistine." He finishes a helping of pasta salad, and adds the plastic bowl to the food sculpture he has methodically constructed out of the contents of the tray on the table in front of him.

But does this new-found identification with the natural, normal world, the comedown after the unnatural excesses of haute-fame, mean Cocker's turning into a hippy? You'd expect the erstwhile Mr Nylon to disagree, but he doesn't. "I could never be a hippy," he says thoughtfully. "I've got this thing about trying to interact with nature because I've been brought up in cities. But there's some good things about hippies. They make fools of themselves, but at least they're having a go. At least they're bothered." The next reference seems very close to home. "It isn't just getting hammered and not giving a thought to things. It's having a go rather than mindless hedonism."

Pastures New: The Big Issue Interview with Jarvis

Pastures New: The Big Issue Interview with Jarvis

"I've been really unreasonable, at certain points, but you don't realise it at the time." He points out that he's not the only one who's lost the plot. "Everyone goes off the rails once or twice. You'd get too bored otherwise." He smiles a mischievous smile, but his next words are more contemplative. "In a way, it can make you a nicer person. You're not so arrogant. You realise you're not so great, you're capable of making mistakes... you're not so fantastic."

"I've been really unreasonable, at certain points, but you don't realise it at the time." He points out that he's not the only one who's lost the plot. "Everyone goes off the rails once or twice. You'd get too bored otherwise." He smiles a mischievous smile, but his next words are more contemplative. "In a way, it can make you a nicer person. You're not so arrogant. You realise you're not so great, you're capable of making mistakes... you're not so fantastic."