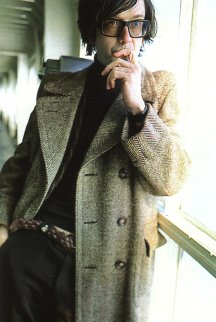

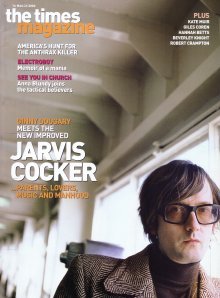

Words: Giny Dougary, Photographer: Mike Persson

Taken from The Times Magazine, 16 March 2002

Something weird is happening to Jarvis Cocker. After years going gloriously off the rails, the lead singer of Pulp has expressed a desire to grow up and live like normal people. Here, he tells Giny Dougary about finding his father after 30 years, the truth about his infidelities - and why he no longer wants to be a celebrity.

Jarvis Cocker - pop star, DJ, and aficionado of Outsider Art - has impeccable manners, which may come as a surprise to those people who dimly associate him with the incident some years ago at the Brit Awards when he mounted the stage and stuck out his bottom in protest at Michael (aka The Messiah) Jackson's peculiarly American brand of saccharine sanctimoniousness.

He first blazed into view in 1995 with Pulp's mega hit single - Common People, Cocker's angry articulation of class division - "You'll never fail like common people, you'll never watch your life slide out of view, and dance and drink and screw because there's nothing else to do" - invoking comparisons with an earlier working-class songwriting hero, John Lennon. His was the voice of youthful rebellion. Despite at 31 being not all that youthful himself, castigated by the defenders of public morality for his rave anthem Sorted for E's and Wizz, which if you actually listen to the lyrics is about the horrors of coming down from a night on Ecstasy.

There was his encounter with the tabloids when a fling with a make-up artist led to lurid headlines about Cocker's sexual prowess which might have been more flattering had he not been involved in a long-term relationship at the time. And then at the height of the mid-Nineties Cocker went off the rails - relentlessly partying with a wiped-out expression on his face, culminating in a dash to New York where he almost went out of his mind alone in a hotel room.

This Is Hardcore, the bleak follow-up to Different Class, was a nervous breakdown of a record - a first-hand documentation of the perils of fame in which Cocker compared celebritydom to a form of pornography. The cover was of a beautiful naked woman who appears to be dead. That was more than three years ago. In the intervening time, Cocker went to ground in an attempt to sort himself out and learn how to be happy without doing himself in. He has renewed a relationship with his estranged father in Australia, rediscovered his childhood pleasures of cycling and country walks, and has a firmer grip on how he wishes to harness his talents.

Pulp's latest album, We Love Life, produced by the reclusive legend Scott Walker, certainly has a sunnier, more life-embracing disposition than its predecessor, despite an occasional detour into death and lost love affairs; and as if to endorse its tide, for every CD sold a penny will go towards the planting of trees in a forest somewhere in England.

In the old days, Cocker insisted on meeting journalists in pubs and caffs but today his management has picked a West End restaurant recently acquired by Marco Pierre White. He arrives only late, for which he is assiduously apologetic, and orders mineral water and crab lasagne after checking that I've been looked after - "Ladies first". A constant refrain of his in die past has been his concern that he suffers from emotional coldness. This is dearly something which must apply to his personal relationships because on a casual acquaintanceship there is nothing remotely chilly about him. In fact, he is strikingly thoughtful and engaged. Unlike most interviewees, he asks as many questions as he provides answers; not as a way of avoiding being put on the spot but because he seems genuinely curious about what other people think. He is fascinated by almost any subject: class, high culture and pop culture. film, art, landscape, what it is to be a man, how to learn to love properly, cooking (he uses Linda McCartney's vegetarian cookbook), housework and looks.

Much has been made, of course, of Cocker's own idiosyncratic looks. He has been pleasantly plagued by his reputation as an unlikely sex god; unlikely because he is excessively tall and gangly and wears thick horn-rimmed spectacles. He is very sexual on stage in a twisted kind of way, kneeling down and moaning and sighing into the mic or gyrating across the stage like a manic puppet who has just learnt to pull his own strings. When we walk through the streets of Soho after the interview I feel like a snail trying to keep up with a lolloping giraffe, although he hardly appears to be rushing at all. Close up, he looks a great deal younger than his 38 years. He has dear pale skin, dark speckled eyes, small teeth, and a certain boyish delicacy about his features.

But the main reason why he is so attractive to women is probably that he is so interested in how they think and what they have to say; an inheritance, he suggests himself, from an upbringing spent almost exclusively in female company. He always maintained that he felt more comfortable with women than men, but he says that he's getting on better with men than he used to do: I think I'm getting more male as I'm getting older," he says.

But the main reason why he is so attractive to women is probably that he is so interested in how they think and what they have to say; an inheritance, he suggests himself, from an upbringing spent almost exclusively in female company. He always maintained that he felt more comfortable with women than men, but he says that he's getting on better with men than he used to do: I think I'm getting more male as I'm getting older," he says.

After his break-up with his steady girlfriend, Sarah, the psychiatric nurse he was involved with at the time of his liaison with the make-up artist, Cocker has squired a number of raffishly glamorous young women, including the American actress Chloé Sevigny. Now the official line is that he is single, although he breaks off at one point during lunch to respond to what is evidently an exciting text message on his mobile phone. There is something about his look of rapt concentration, coupled with a slightly idiotic grin, that gives the game away. Is it romantic, possibly? I ask. "Probably," he says. So are you writing something romantic back? "Trying to, yeah," he replies, typing in the letters. "Sorry, I'll be finished in just a second." Are you in love with someone right now as we speak? "I might be."

He is understandably coy about the identity of the woman since whatever it is that is between them seems to be at a formative stage. He won't even be drawn on what she does for a living, so I try a few outlandish guesses: politician? "No"; traffic warden? "Definitely not"; hairdresser? "No way"; therapist? "No, no, no"; make-up artist? "Oh, get lost. No." Was he mortified by that tabloid exposure? I wonder. "Yeah, for me who's a person likes it all to be a bit surreptitious and secret, it was pretty devastating really. And also because I was still going out with someone so, yeah, it was awful" he says.

I have the feeling, not from what he says so much as the mournful expression which descends on his face, that the relationship with Sarah, the nurse, and its untimely end, was terribly important to him. When I ask him outright, he admits it was. Is he someone who falls in love easily? "No. I've not had that many major relationships, I've not had very many at all." He says that he has only been chucked once in his life and he couldn't bear the rejection: "Because no matter how badly you behave or whatever, you always think, 'God, but I'm brilliant really, aren't I?' And then if someone says, 'No, you're not, you shit, goodbye', it hurts your pride. I mean, it does your head in." Might it not be good for you to be at the receiving end for a change? "Yeah, it can shock you into realising something about yourself, you know, jolt you into a form of awareness."

Has he managed now that he is approaching 40 to thaw his emotional coldness? "I'm working on getting warmed up at the moment," he says. It's not a question of who he's involved with, he says: "More that you have to think to yourself why are you like that? You have to try and get over it, don't you?" When I ask him whether he would consider doing therapy, he says he doesn't know but he's probably too mean to fork out the money. He agrees that failure is more interesting to write about than success, in love as with everything else, but he has an ambivalent attitude to most writers' self defence mechanism that the more painful the personal setback, the stronger the creative material. "I don't know whether that's good because in some ways it seems slightly inhuman to think like that. Do you know what I mean?" he asks. But isn't that sliver of ice an intrinsic part of being a writer; a sort of insulation from the buffets of life? "It is, but if it stops you from forming meaningful attachments, then that's bad, isn't it? Isn't it just a way of keeping the world at arm's length?"

Cocker has said that past lovers have felt pretty bitter about featuring so prominently in his songs, since his lyrics are so nakedly autobiographical. The rich Greek girlfriend, and fellow student of Cocker's at St Martin's College of Art, certainly cannot have known what she was unleashing when she asked the bloke with the northern accent to show her what common people do. I wonder whether it's part of the fame trap that the people who were once in your life feel aggrieved and exploited when you move on and become successful on what they see as the back of their stories.

But, no, he says, "It happened mostly before we got famous with this one particular girl that I went out with. Because - and I can understand it - it is true that if in your personal life you don't really discuss things that much and then you are quite personal when you come to writing, then I guess that person that you're with has got quite a big right to get upset with you." But would he say that the song is more important than the person who prompted it? "It depends on the person, really, I think. The thing about creating things is that it's often inadequacies or things that you feel are wrong or just little quirks or whatever that make you express yourself in that way," he says.

"Often that's why people do create, because they feel that something is missing from their life or that they can't do something in their normal life so they have to do it another way. Maybe in a way that they feel is safer. Because to express an emotion on a stage, to have dramatised it by putting some music behind it... and to play to an audience when you don't really see individuals but just a mass of people, is a very self-aggrandising way of expressing stuff; it's kind of trying to make it more noble. You know, it's always easier to do a grand gesture than it is to sit in a room with one person and just discuss exactly what it is that is bugging you. It's like in the foreword to - I think it's that Beautiful Losers book that Leonard Cohen wrote, where he said it's much easier to show a scar than it is a pimple. A scar is something from a battle where a pimple is just a fault, and I do think there's something in that. That if you are serious about ever having a proper relationship with somebody you have to find some way round that."

I wonder whether Cocker was ever embarrassed by some of the things he did and said when he was razzling around town. Even quite recently, referring back to that time, he was quoted in a men's magazine saying, "I had access to the finest quality fanny available", which hardly chimes with his claim to me that given the way he was brought up, there's no way that he could think of a woman as an object. "It just came out," he says looking suitably chagrined, "and I knew as soon as I said it that it would probably end up in the headline. I don't know how it slipped out. But I did add - what was it? - that it didn't seem to really satisfy me or make me happy, so that was meant to undermine what I said."

I wonder whether Cocker was ever embarrassed by some of the things he did and said when he was razzling around town. Even quite recently, referring back to that time, he was quoted in a men's magazine saying, "I had access to the finest quality fanny available", which hardly chimes with his claim to me that given the way he was brought up, there's no way that he could think of a woman as an object. "It just came out," he says looking suitably chagrined, "and I knew as soon as I said it that it would probably end up in the headline. I don't know how it slipped out. But I did add - what was it? - that it didn't seem to really satisfy me or make me happy, so that was meant to undermine what I said."

For an introverted young man who grew up believing that he was a spectacular turn-off, one can imagine how it went to his head when models and actresses started to throw themselves at him. Was it like being in a sweet shop and being told that you could take your pick? "Yes, but if you went into the sweet shop and stuffed your face, you'd eventually throw up, wouldn't you?" he says.

He used to talk a lot about his inability to cope with being famous - once comparing it to a nut allergy - but now he's reluctant to dwell on it because he doesn't want to sound like a "moaning minny". Cocker was already in his early thirties when he hit the big time; one might think that having a grounding in normality should have helped to protect him from the pitfalls that beset younger pop stars who become celebrities before they've had a chance to grow up. "No, I think it made it worse," he says. "If you're only 19 and you haven't really got a life, you can think, 'Oh yeah, this is what my life's going to be like now.' But at the age of 32, you have got a life and suddenly you're presented with another one - so it's like all your experiences up to that point don't count for anything. It's quite a weird feeling."

At one point during lunch, we talk about our shared fascination with the polar regions. What sends him, he says, is the vision of an infinite, empty landscape "where you've got no evidence of man ever having had any influence". The pleasure of his visit to the Arctic Circle was somewhat challenged, however, by his hotel having curtains like tissue paper despite the perpetual daylight: "I ended up getting the duvet cover off the duvet, tacking it up and it still wasn't dark enough. So then I got the mattress off the bed, put it on its side and kind of wedged my head underneath it. Then it was quite dark. But it was a very uncomfortable way to sleep."

He tells me how it made an impression on him when he heard a polar explorer on Desert Island Discs talking about how his wits began to turn as he made his solitary trek to the South Pole. "I don't know whether he was making it up, but he reckoned - because it was completely blank and he was walking over rules and miles of white all the time - that he started hallucinating after the fourth or fifth day. Because there was no outside stimulation coming in, it was like the brain creates something because it can't handle nothingness. And he reckoned that during that walk to the South Pole, he remembered every single thing that had happened to him in his life up to that point."

Cocker's own private journey to Antarctica took place in that hotel room in New York, which he describes as the most frightening experience of his life. Apart from the drugs he was taking, he was also drinking so heavily - this was before the tabloid revelation that his father had been an alcoholic - that his hangovers had taken on the form of a psychosis: "I really thought I was losing my mind," he says. The horrid irony was that although his flight to New York had been a desperate essay to restore his sanity, it only served to tilt him over the edge. "I was attempting to get back into my head after a long period of getting out of it, and I went thinking that I could go there and not so many people know me but I can still talk the language. That was my logic. But what I failed to think of was the fact that my social skills which were never very good anyway - had dwindled to virtually nothing. And so I ended up cowering in my hotel room and a bit like the man at the South Pole, going off my head."

There's a song on This Is Hardcore, called A Little Soul, which is strikingly different from the brittle sleaziness of the rest of the record. It has a melancholy, Dylanesque feeling about it; the lyrics are a bitter, self-pitying lament from a failed father to his son. "Everybody's telling me you look like me but please don't turn out like me... Yeah, I wish I could be an example. Wish I could say I stood up for you and fought for what was right. But I never did. I just wore my trenchcoat and stayed out every single night... I did what was wrong, though I knew what was right. I've got no wisdom that I want to pass on... I have run away from the one thing that I ever made."

Cocker wrote the song, which fairly smarts with anger fuelled by a feeling of double-abandonment, after the Mail on Sunday tracked down his father in the hippy outpost of Darwin at the tip of Australia's Northern Territory. At the time Jarvis said that he found it hard to understand how his father had chosen to talk about his son to a British tabloid reporter when he had not bothered to make any contact with the family he left behind in Sheffield when his only son was seven years old.

In Sydney in the Eighties, the coolest DJ on the hippest radio station, ABC's Triple Jay, was a guy with a Sheffield accent called Mack Cocker. I was living there at the time and loved the eclectic records he played and his dry; slightly grumpy delivery. Because of the name and the Sheffield background, everyone assumed that he was Joe Cocker's brother, and Mack Cocker apparently didn't go out of his way to disabuse people of that impression. In fact, the closest he got to any kinship with the singer was playing a one-off gig with him in some northern club.

One evening, I was sitting with some friends in a pub not far from Triple Jay's office and heard the unmistakable voice of my favourite DJ. Being a daft twentysomething, and having just seen Clint Eastwood's directorial debut in which he plays a radio DJ who is stalked by a female fan, I asked the barman to send Cocker a pint with a note which read, "Play Misty For Me". I didn't dare look to see Cocker's reaction but if I had, the first thing I'd have noticed was his extreme height and skinniness. Thrown off by the false Joe Cocker connection, it wasn't until I read Jarvis's cuts that I realised that his father was the same man on whom I'd played my childish prank all those years ago. "That's it, is it?" Jarvis says when I finish the story I thought you were gonna tell me something that'd make me throw up me dinner... like that you'd gone home with him or something," he laughs with palpable relief.

It was writing the song about his dad which made him decide that he had to fly to Australia to see him. "I thought, 'Well, if I've written a song about it, it must mean that it's on me mind in some way.' So pretty soon after that I said to my sister, Saskia, 'I'll pay for us to go over,' because I don't think I could have gone on me own." Their mother was fine about it, he says, because she understood her children's need to find out about their father for themselves. "I mean, it was probably just a selfish impulse on me part to want to go. A friend of mine's dad had been really ill just before then and that got me thinking, 'Well, if I don't make an effort to get to know him a bit now, if I leave it and he dies, then I'll feel really... well, I'll probably regret it in later life.'"

Naturally I want to know what happened to Mack Cocker in the last decade. Did he go off the rails like his son, and at about the same time? What on earth prompted him to leave a sophisticated city like Sydney where he had a huge following, and move to such a remote place? How bad was his drinking? But Jarvis cannot provide an answer to any of these questions: "I don't really know what happened, to he honest," he says. "There's lots of things about him that I don't know. He did have a bit of a thing with drinking, so maybe he had to move away because of that - but I'm not really sure." It's rather sad that it wasn't until I told him that Jarvis had any idea that his errant father had made such a success of himself - at least professionally. How tough to have a stranger fill in the gaps of your family history.

It's hard to imagine what that reconciliation must have been like; to come face to face with someone who looks just like you, after an absence of 30 years, in damp, subtropical Darwin. Did Jarvis actually like his father? "Well, it's very strange when you meet somebody who obviously in terms of a blood tie you're very close to, but haven't seen for quite a bit� I mean, you don't actually know them, so it is a very strange feeling." Did he have any memories of being with him as a small boy? "I remember having a bath with him, and daft things like him watching rugby on the telly drinking a can of beer, or the way when he burped he always used to say 'Archbishop of Canterbury,'" he chirrups.

It's hard to imagine what that reconciliation must have been like; to come face to face with someone who looks just like you, after an absence of 30 years, in damp, subtropical Darwin. Did Jarvis actually like his father? "Well, it's very strange when you meet somebody who obviously in terms of a blood tie you're very close to, but haven't seen for quite a bit� I mean, you don't actually know them, so it is a very strange feeling." Did he have any memories of being with him as a small boy? "I remember having a bath with him, and daft things like him watching rugby on the telly drinking a can of beer, or the way when he burped he always used to say 'Archbishop of Canterbury,'" he chirrups.

Was he overwhelmed by feelings of resentment that his father had stayed away from him for all that time? "Yeah, but at the age at which we went - I was 35 and my sister would have been 32 - although you can't help having those feelings, you're already formed as a person. So really the time when that person could have given you a great deal has gone. I mean, obviously you can get on with them and it would be nice to get on with them rather than not to get on, but in terms of aiding your development or whatever, it's too late."

Cocker always used to describe himself as somewhat emotionally arrested. Even now, he lives a life more conventionally suited to a student than someone who is hedging towards his middle years, sharing his flat in Hoxton with a group of guys and one woman. But I felt when we spoke that there was a sense of urgency about his desire to grow up and tackle the challenges of life in a more mature way. His new-found resolve was reflected on several levels. We didn't really talk about drugs and he certainly didn't come over all Nancy Reagan, but he did say that he thought cocaine was dangerously deceptive: "The horrible thing about it is that people think it makes them more sociable and outgoing but the end result is that it makes you really introverted. And you're really not bothered about what other people say because you just gab on all night. Everyone's talking but nobody's listening"

So does he think there are more useful things to do with his spare time now? "I hope I've realised that now, yeah." Do you feel that you're out of that thicket? "I bloody hope so."

But the main reason why he is so attractive to women is probably that he is so interested in how they think and what they have to say; an inheritance, he suggests himself, from an upbringing spent almost exclusively in female company. He always maintained that he felt more comfortable with women than men, but he says that he's getting on better with men than he used to do: I think I'm getting more male as I'm getting older," he says.

But the main reason why he is so attractive to women is probably that he is so interested in how they think and what they have to say; an inheritance, he suggests himself, from an upbringing spent almost exclusively in female company. He always maintained that he felt more comfortable with women than men, but he says that he's getting on better with men than he used to do: I think I'm getting more male as I'm getting older," he says. Jarvis Gets Real

Jarvis Gets Real I wonder whether Cocker was ever embarrassed by some of the things he did and said when he was razzling around town. Even quite recently, referring back to that time, he was quoted in a men's magazine saying, "I had access to the finest quality fanny available", which hardly chimes with his claim to me that given the way he was brought up, there's no way that he could think of a woman as an object. "It just came out," he says looking suitably chagrined, "and I knew as soon as I said it that it would probably end up in the headline. I don't know how it slipped out. But I did add - what was it? - that it didn't seem to really satisfy me or make me happy, so that was meant to undermine what I said."

I wonder whether Cocker was ever embarrassed by some of the things he did and said when he was razzling around town. Even quite recently, referring back to that time, he was quoted in a men's magazine saying, "I had access to the finest quality fanny available", which hardly chimes with his claim to me that given the way he was brought up, there's no way that he could think of a woman as an object. "It just came out," he says looking suitably chagrined, "and I knew as soon as I said it that it would probably end up in the headline. I don't know how it slipped out. But I did add - what was it? - that it didn't seem to really satisfy me or make me happy, so that was meant to undermine what I said." It's hard to imagine what that reconciliation must have been like; to come face to face with someone who looks just like you, after an absence of 30 years, in damp, subtropical Darwin. Did Jarvis actually like his father? "Well, it's very strange when you meet somebody who obviously in terms of a blood tie you're very close to, but haven't seen for quite a bit� I mean, you don't actually know them, so it is a very strange feeling." Did he have any memories of being with him as a small boy? "I remember having a bath with him, and daft things like him watching rugby on the telly drinking a can of beer, or the way when he burped he always used to say 'Archbishop of Canterbury,'" he chirrups.

It's hard to imagine what that reconciliation must have been like; to come face to face with someone who looks just like you, after an absence of 30 years, in damp, subtropical Darwin. Did Jarvis actually like his father? "Well, it's very strange when you meet somebody who obviously in terms of a blood tie you're very close to, but haven't seen for quite a bit� I mean, you don't actually know them, so it is a very strange feeling." Did he have any memories of being with him as a small boy? "I remember having a bath with him, and daft things like him watching rugby on the telly drinking a can of beer, or the way when he burped he always used to say 'Archbishop of Canterbury,'" he chirrups.