From gauche to River Gauche

From gauche to River GaucheThe sleeve of his debut solo album reads just Jarvis - no surname. If only for the fact that it instantly serves to remind us that we have long been on first-name terms with the sometime Pulp frontman, it's an assured move. After all, who else would you call out if new Family Fortunes host Vernon Kaye asked you to name a famous Jarvis? A chain of hotels? Martin Jarvis? Until recently Cocker would have been inclined to agree. "It was funny," he explains, unsmilingly. "I flew to Sheffield recently, and the guy at the car-rental desk recognised me. He said: 'Have you got a name for your new album yet?' And I said, 'Not really, but I'm just thinking of calling it Jarvis. And he said: 'What you need to do is call it "The Jarvis Cocker", because when I said that you'd been here the other week, everyone said: 'What? The Jarvis Cocker?'" Cocker takes a sip from his Evian bottle. "You see, that made me think that there might actually already be more than one Jarvis Cocker in people's lives."

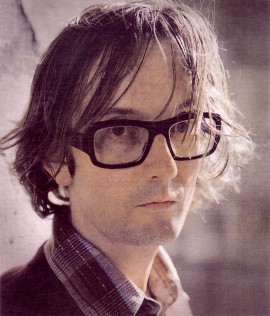

Now 43 and living in Paris with his French wife Camille and son Albert, Cocker says he is at a level of celebrity that feels comfortable. Like Stephen Fry, Quentin Crisp and John Peel (who gave Pulp their first airtime, back in 1981) before him, his is the toasty, friend-of-the-family level of recognition afforded to great living Englishmen. His spur-of-the-moment decision to sabotage Michael Jackson's cod-messianic 1996 Brits performance is undoubtedly a factor here - although, of course, the irony is that the notoriety it conferred upon him almost drove him insane.

But, until that moment, Cocker had rather enjoyed being a pop star. When I interviewed him in 1995 - after Common People had become a hit but before the release of the album Different Class - he sounded like a man on a mission. "I was very aware," he said, "that people are going to listen to these new songs. And you know, it would be terrible to hang around for all these years trying to grab people's attention and forget what it was you wanted to say in the first place. Not that I've any profound message for mankind, but two-thirds of Different Class was written when Common People was still in the charts, and I think it shows." Scan the lyrics now and, at times, it reads like a state of the nation address. People who once volleyed abuse at him for his Mr Muscle looks were the subject of his ire in Mis-Shapes, while the psycho-sexual class warfare of I Spy - "I will take you from this sickness, dinner parties and champagne/ I'll hold your body and make it sing again" - still sends shivers up the spine.

Cocker has been a fixture in our cultural fabric for so long that it's hard to remember how much his rise to glory seemed like the result of a massive clerical error in pop heaven. In the 1980s, when Pulp were an oddball indie outfit struggling to get attention outside their native Sheffield, a cursory listen to many of their records suggested that their frontman was more likely to end up in an institution than on Top of the Pops. A case in point was Pulp's second album, Freaks, written while Cocker was living "in this weird place above an old silk factory where all the strange characters of Sheffield used to gather. There was one bloke who was going to build a helicopter from bits gathered from army surplus stores. And another bloke with a monk's outfit and a pet rat that used to shit everywhere. He eventually died of a heroin overdose.

"It was a laugh at first, but it just seemed that we were all becoming freaks, that we weren't legitimate members of society - and I hated that."

This being 1986 - the year in which Dire Straits' Brothers in Arms outsold every other album in Britain - people would have thought you nuts to suggest that Cocker might ever end up on the cover of Smash Hits, dressed as an astronaut. By the time it finally happened though, in 1995, Cocker was in no mood to revel in it. "For a long time, Pulp was our fantasy world where we could make the rules and decide how it all worked. But when you get famous, that gets taken out of your hands." Within a 12-month period Cocker had felt both extremes of tabloid attention - vilification over the diagram of a drugs-wrap on the sleeve of Sorted for Es and Wizz and adulation over his ad hoc usurping of Michael Jackson at the Brits. Even his estranged father - an Australian DJ called Mac - reappeared, blithely telling reporters just how proud his son had made him.

A memory of standing beside Cocker as he queued for the lavatory at a Belle & Sebastian show in 1997 lingers primarily because it was impossible to sustain any kind of conversation with him over a rising crescendo of Jacko- related "well-done"s. Amid persistent rumours of a heroin "scene" centred on the artier Britpop axis of Pulp and Elastica, Cocker's inability to escape his own ubiquity was detailed chillingly when Pulp finally resurfaced. This is Hardcore confirmed that Cocker no longer desired the fame he had sought so assiduously. One B-side entitled The Professional went: "Just another song about single mothers and sex... OK, you've heard it before/ It's nothing special, but it's a living, can't you see?/ I'm a professional."

Beneath the panic and the paranoia, however, Cocker's bone-dry sense of humour seemed to stay just about intact. With two days to go before Pulp began touring This is Hardcore, Cocker enlisted the help of Gareth Dickinson, a student who had pretended to be him on Stars in Their Eyes a year previously. "I had got into my head," explains Cocker, "that I could no longer be the person that people wanted me to be, so I came up with what I thought was a fantastic brainwave. I would employ him to be the me that people wanted to see. So each gig would start with him lit up from the back, striking some classic 'Jarvis' poses. Meanwhile, I would be doing the singing, hidden behind a speaker stack because his voice was awful. I mean, I'm not saying mine's brilliant, but at least I sound like me. He didn't sound like me at all. Anyway, it worked quite well. The only problem was that he was a bit chubbier than me and he ended up ruining my best velvet suit after doing a particularly extravagant leg movement. I never really forgave him for that."

That his doppelgänger can no longer make a living pretending to be him is, says Cocker, good: "Being at that level of fame where you have professional lookalikes isn't especially enjoyable." After Pulp bowed out with 2002's redemptive swansong We Love Life, Cocker told himself he was retiring. "What with approaching 40, it seemed the dignified thing to do," he reasoned. Prior to that he had never considered fatherhood as an option, partially because of the writer Cyril Connolly's celebrated contention that "there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall". But if Cocker planned never to make another record that would no longer be a problem.

As it turned out, the pram in the hallway hastened the creation of several of the songs that finally made it on to Jarvis - most notably Disney Time, which attempts to establish common ground between porno films and what Cocker calls the "pornographically cosy depiction of family life in Disney films". However, he's swift to add that he has a lot of time for earlier animations, such as Dumbo and Bambi - "the only problem is that, because we never had DVDs or videos when I was Albert's age I had never seen a lot of these films. When it got to the bit in Dumbo where his mum gets taken away and put on a railway cart and there's a sign with 'Mad Elephant' on it, it destroyed me for 20 minutes."

You can't help thinking that at some unconscious level there may have been an element of creative self-preservation in Cocker's relocation to Paris. He has always seemed more comfortable anonymously gazing out at society from its margins - and, speaking on Desert Island Discs last year, it seems that he finally got his wish. "I don't know anyone in Paris apart from my wife," he told Sue Lawley. I've always been furtive," he elaborates now. "And moving to Paris has allowed me to indulge my furtiveness. Not for any sinister reason, I might add. I just find that that's where I get my ideas from."

Certainly, it isn't hard to trace a line from the reluctant freak of 1986 to the altogether more reconciled one of Jarvis. Only Don't Let Him Waste Your Time sounds like a bona-fide chart contender - and he wrote that for Nancy Sinatra's self-titled comeback album three years ago. By contrast, bleak 21st-century vignettes such as Fat Children and Big Julie - not to mention his Live 8-inspired download hit (Cunts are) Running the World - suggest the completion of a circle.

With Albert now 3, it surely won't be long before Cocker rummages through his archive and shows him that Smash Hits cover? That's surely something to be proud of, isn't it? "I wouldn't show him that one," he says, flatly. "It's too embarrassing." Embarrassing? Why? Cocker takes a deep breath. "Well, a psychiatrist would have a field day with this, but as a kid, I wanted more than anything to be an astronaut. So, really, you would think that being asked to dress up as one would be one of the pinnacles of my pop career. "The thing is, I wouldn't have minded if they'd got a proper space suit like the old Nasa ones, but it was really poor. They got a pair of silver trousers which were tapered - and I never wore tapered trousers - with a silver shirt and a plastic space helmet that they'd obviously got from the fancy-dress shop. It was laughable. So, because they did it so crappily, it was like somebody taking your dream and just making it rubbish. And in a way that's what can happen with pop stardom itself."