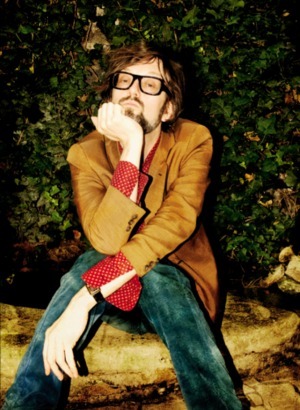

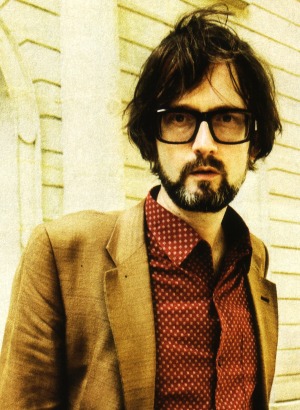

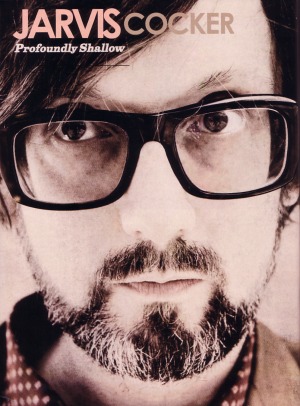

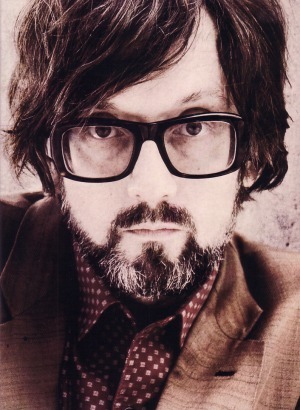

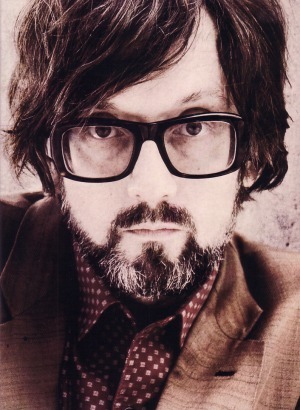

Jarvis Cocker: Profoundly Shallow

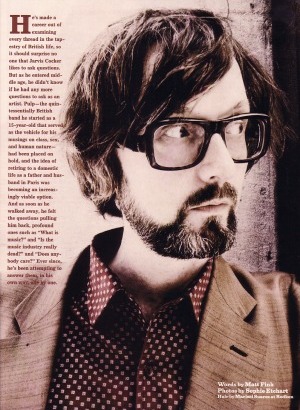

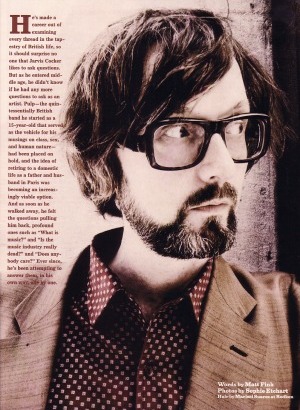

Jarvis Cocker: Profoundly ShallowHe's made a career out of examining every thread in the tapestry of British life, so it should surprise no one that Jarvis Cocker likes to ask questions. But as he entered middle age, he didn't know if had any more questions to ask as an artist. Pulp - the quintessentially British band he started as a 15-year-old that served as the vehicle for his musings on class, sex, and human nature - had been placed on hold, and the idea of retiring to a domestic life as a father and husband in Paris was becoming an increasingly viable option. And as soon as he walked away, he felt the quetions pulling him back, profound ones such as "What is music?" and "Is the music industry really dead?" and "Does anybody care?" Ever since, he's been attempting to answer them, in his own way, one by one.

Today, though, sitting in his hotel room in Barcelona, Spain, waiting to go see Lightning Bolt perform at the Primavera Sound Festival, Cocker is more interested in talking about how much his knee hurts from all the stomping he has been doing during band rehearsals. "These are the perils of being an older performer," he says drolly. If he ever thought he was invincible, he no longer suffers from such delusions, and the man who crashed the stage at the 1996 Brit Awards to disrupt a particularly self-aggrandising Michael Jackson performance, isn't about to take himself too seriously.

"When people form bands, they often have that thing, like, 'This fucking band is going to change the universe. I can see things that no one else can see.' I don't know if I'm mellowing, but I think you have to get over yourself," he says. "Obviously, everybody in the band has got ego, and that's part of why you get on the stage. You're saying, 'C'mon, listen to me. I'm fucking great.' Generally speaking, if I've got a skill, it's to do with observation and what I write about. I do tend to be obsessed with trivia, therefore, I am profoundly shallow," he laughs.

"But people are always bigging themselves up with songs, and I think it would be nice to write a song that said, 'I'm a useless piece of shit.' There was a Leonard Cohen quote that I really liked that said, 'It's easy to show a scar. It's harder to show a pimple.' Everybody likes to say, 'Yeah, I've suffered. I'm fucking deep. Hear my anguish.' That's easy. But to show something that you're embarrassed about or that doesn't show you in a good light, it's braver to do that and run the risk of looking foolish," he says soberly. "I've always liked to do that, because if you manage to get away with it, it's quite satisfying." With Further Complications, Jarvis Cocker shows his blemishes.

Further Complications is not the first time Cocker has written about sex, nor is it the first time he has told an embarrassing story about himself. He already proved his mastery of these topics on 1994's His 'n' Hers, the fourth Pulp album but first to register with listeners in any significant way. Already 30, he sounded at least 10 years younger, writing songs from the perspective of a neurotic and frustrated man, someone whose sexual obsessions never resulted in conquest, only betrayal.

Now 45, Cocker has nearly become the confident sexual adventurer that the conflicted and awkward storyteller on His 'n' Hers dreamed of becoming. Presenting himself as a raw streak of humanity, he is neither self-pitying nor defiant on Further Complications. At times ugly and uncomfortable, the sex he writes about is largely guilt-free and without attachment or repercussions, the story of a horny older man going for one last swipe at youth. Like Serge Gainsbourg or Leonard Cohen before him, Cocker presents himself as a middle-aged man who desperately wants to get his groove on, preferably with a 23-year-old woman. He does just that on Angela, announcing 'I can feel the sap rising tonight' before describing himself as 'a dry stick at the end of a branch.'

Even more perverse is Fuckingsong, a track designed as a sexual apparatus of sorts, a sonic strap-on that can penetrate every woman who hears it. "It could be the ultimate in safe sex," he explains. "In singing that song, you reach more women than you ever could in real life. But what I'm saying on the flipside of that is that for the woman involved, it's much better for her to have a relationship with that song than it is to have a relationship with me. Because I'm human and fallible and I'll get drunk and not turn up when I'm supposed to turn up, whereas that song, every time you put it on, that CD will perform exactly how you want it. It will always do its best. So you're better off with the song version of me than you are with the actual real person. That's basically what I'm saying."

Further Complications also isn't the first time that Cocker has written songs with a self-effacing tone. Having claimed a spot in the burgeoning Britpop movement with His 'n' Hers, he turned to more everyday themes with the anthemic Different Class, the 1995 release that became an instant classic, and one whose success touched off the few years of doubt and self-searching that culminated in 1998's darkly enveloping This Is Hardcore. That album, a study in fear, regret, and the lingering dissatisfaction that accompanies getting what you want and not being content with it, added yet another dimension to Cocker's persona, demonstrating that he was capable of not only astute social commentary, but personal catharsis as well. He wrote about wife-beaters, bad friends, and ruined relationships, all the while cutting himself with jokes about his inability to do anything about it all. At least on the surface, the Jarvis of Further Complications seems to be far less, well, complicated.

For a songwriter of Cocker's stature, a poet and chronicler of British life in the same way that Ray Davies was for an earlier generation of English pop fans, a song like I Never Said I Was Deep is simultaneously puzzling and strangely fitting. A four-and-a-half minute soul ballad wherein Cocker slowly attempts to convince his listener that he's morally defective, lacking in cleverness, and 'not looking for a relationship, just a willing receptacle,' it's also the centrepiece of the album, the summary statement for a resolutely libidinous and lecherous song cycle. He might have made his career writing about common people and common problems, but Cocker never seemed quite like us. He was always too smart, too fashionable, too graceful. He never said he was deep, but he's fighting long odds to convince us that he isn't.

"But that's how I see myself," he says of I Never Said I was Deep. "Like I said, I think I may have that phrase on my tombstone. I also hope it's amusing. I think it's funny to say that thing about yourself. But often what happens with me is that I'll say something that's kind of funny but that is, unfortunately, also true," he laughs. "I like it when it's both things at the same time. I like it when you're not sure if it's serious or not. But it is a problem with me. There is real emotion in that song. It's not like Jon Bon Jovi emotion. But it wouldn't work if it didn't have a kernel of truth in it. If it was just a joke, what's the point, because once you've heard a joke once or twice there's no need to hear it again. Generally speaking, for my music, it has to have that emotional core to it, because otherwise why would you get on stage night after night and sing that song? There's got to be something that you get from it. I don't think it should be purely a cathartic exercise and smear your blood all over the stage and fuck everybody else. But I also think that the fact that you're on a stage means that you are an entertainer and you have to accept that, as well."

Even so, some people aren't ready for a songwriter of Cocker's status to spend an album trawling for flesh. Though Further Complications isn't without nuance, it is a startlingly straightforward statement for an artist who has written probingly about class identity, cultural decay, and political power. But Cocker appears to be neither conflicted nor confused about his myopic hedonism, and aside from Slush, a meditative elegy for an Earth soon to be destroyed by global warming, there are virtually no songs that appear to warrant a beneath-the-skin reading.

"Particularly in the UK, this record got some weird reviews," he says. "Some people really liked it, and then other people-some of them people I know, journalists that I've met in the past-really seemed to be offended by it," he says, laughing. "And I kind of liked that, because I don't want to make a record that's exactly what you expect from a Jarvis Cocker record. Because just either listen to the last one or go and listen to one of your old Pulp records. I cannot see the point. Now some of the lyrical subject matter might be a bit dodgy. Saying that you're not looking for a relationship, you're looking for a willing receptacle is... kind of gross," he says somewhat apologetically. "I was brought up in a very female-dominated environment, and I generally try to respect women and try to take notice of them and treat them as equals. It's never really come to mind not to treat them as equals. So that statement in that song is my intention to grapple with unsavoury thoughts. Everybody has unsavoury thoughts, don't they? I just think that rather than deny them, grapple with them, and maybe you'll work through that thought and go somewhere else. Conflict or iffyness and dodginess or whatever you want to call it is generally more entertaining than everybody being nice to each other. People love to see people getting blown away in films, but it doesn't mean that people really approve of murder, does it? It's just that that's what turns people on, and I'm no different."

Cocker admits that he was only "dimly aware" of Steve Albini before Steve Mackey, a Pulp alumnus and member of Cocker's new band, suggested that they make some exploratory recordings at Albini's Chicago studio while in town for 2008's Pitchfork Music Festival. Having noticed that many of the songs from his 2006 solo debut had become tighter and more dynamic after performing them every night, Cocker decided that he'd like his next effort to be a more spontaneous, live-in-the-studio affair. That album, the musically sophisticated and thematically diverse Jarvis, was exactly the kind of album he didn't want to make as a follow-up, and when making a recording based around the sounds of a band playing in a room, there's no one you'd rather record with than Albini.

"That sounds very simple and maybe people think that's how all records are done," Cocker says of Albini's hands-off recording style. "But it seems very rare that that actually happens now, and it's weird, because that's the most natural thing in the world, isn't it? It's as if saying, 'Oh yeah, we decided that we were going to play the songs to people before we recorded them' is some kind of major new innovation. Well, when people invented music, it was a long time before recordings were invented. People were playing music a long time before that for people. I guess that's the weird thing, that in the modern age, the artefact has in some ways taken the place of the actual thing that it's there to be a record of."

Recording outside of the UK for the first time, Cocker found that Albini held steadfast to his working rules, insisting that the band be present for mixing and rarely giving any feedback on decisions that he believed were better decided by the band. The result is the loudest album Cocker has ever made, one with guitars that careen and squawk, drums that crash and lurch, and vocals that catch elbows in the mouth trying to get to the centre of it all. For Cocker, a songwriter who has always prided himself on being a pop artist first and foremost, the album has the distinction of being both his most melodically direct, yet least sonically sophisticated.

"I couldn't say that I'm a particularly sophisticated person," he says. "I don't think it's a particularly sophisticated record, and I didn't want it to be that sophisticated. I kind of wanted to make a fairly light-hearted record, but not a throwaway record. Something like Angela I was pleased with because it was under three minutes. I was always disheartened with Pulp, where I thought I was writing pop songs, and yet they always seemed to clock in at the 4:45 mark. And I thought, why? That's not right. Pop songs should be three minutes or under. So I've worked on cutting out the unnecessary bits of songs, and that might sound like a dry academic exercise, but I was absurdly pleased that Angela was under three minutes. So that was quite a big factor in having it as the lead track off the record," he says, sighing. "I never said that I was deep."

He might not be deep, but such discussions naturally connect back to the questions Cocker has been asking since he placed Pulp on hiatus. At the start, he wasn't sure what answer he was searching for, but he suspected that music - if not art, in general - was becoming little more than another lifestyle choice, something that was passively experienced instead of vigorously engaged. He addressed the question while writing in The Observer Music Monthly, gave lectures on the topic, and created multimedia shows as curator of the 2007 Meltdown Festival in London. He made Further Complications because he wanted to get his hands dirty in the recording process, to be an active participant in every phase of its creation. During the first week of May 2009, he moved one step closer to finding his answer.

Setting up in Paris' Galerie Chappe for a week, every day from noon to 6:00pm, Cocker and his band made an exhibition of themselves. They performed shows for children; they provided the soundtrack for yoga, aerobics and Pilates classes. They allowed visitors to write suggestions on note cards that were used for improvisation and encouraged attendees to bring their own instruments to jam with the band. They tried to see how quietly they could play, they played for dancing, and they played songs from Cocker's new album. The point of the exhibition was clear: Music is everywhere, and if it's part of your life, you might as well participate with it.

"It's kind of weird that while we're saying that the industry is dead, it seems to be more widespread," he explains. "You buy a phone and you get free downloads and people can carry around so many songs on their MP3 player - more songs than they could probably ever listen to. So I was trying to think about what music was for me, because I do think that I've heard songs that have changed me or have changed my view of the world. And if it's surrounding you all the time, and you spend your whole life on shuffle, it's kind of weird. I realised that when I got a computer, and I started putting songs on it, there are certain songs that you don't want to stumble across on shuffle. There are certain songs that you put on for a specific purpose, either you're really down or you're really up. You don't want to have them just randomly come into your life. You want to actually choose to listen to them, so I erased quite a lot of them. I've had a computer for 10 years, and yet I've still only got 2,297 songs in my iTunes library. So it flabbergasts me that some people have 15,000 or 30,000 songs. I don't know how they do it. I work in the music business - music is my life - and yet I've only managed to put that many songs onto my hard drive. It kind of mystifies me. For me, since the MP3, that's kind of turned music into the equivalent of stamp collecting, in that it's just like filling albums up, filling your collection of books up, rather than actually valuing the thing for its own properties. I'm probably exaggerating that, but I think there's an element of that."

If Cocker seems like a modern anachronism, an idealist who can't keep up with the pace of the changing times, don't be deceived. As much of a contributor as he is a critic of pop culture, he's just as likely to praise the democratising effect of MySpace as he is to lament the loss of significance of the British pop charts. He's living proof that culture is a constantly flowing stream, and that we're all wading in it. We might as well learn to swim.

"That was the point of that thing that we recently did with occupying this gallery in Paris," he says. "I think it's important to get across that you don't have to be a spectator. You can participate, as well. It's kind of like the consumer society has moved into areas that it shouldn't be. I guess that's what I was getting into with that song Cunts Are Still Running the World a couple of years ago. That to apply the free market capitalist system to every aspect of life can't work, because it might work as a market system, but to apply it to activities with a moral dimension is inappropriate, because there's no moral dimension to capitalism. It's just an economic system. But because it's the dominant system, people can't help but get sucked into it, so you think of culture maybe as just something that you consume. You see that in people's MySpace profiles where they just list all the bands that they listen to. It's like looking at someone's shopping list. So that's why there's the line in Further Complications: 'Don't write a novel / A shopping list is better.' That's why I think this current economic crisis, which everybody is sick of people talking about, I hope it will have a positive effect, because it has discredited the free market capitalist system. It cannot work unregulated, and it isn't the model for everything. That's good, because people will hopefully start inventing things for themselves because A) it's cheaper, and B) it's more fun, as well."

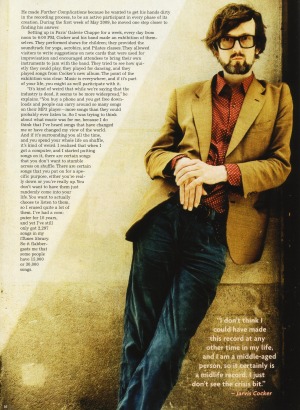

Jarvis Cocker wants you to know that Further Complications is not a breakup album. Although he might stomp through its 11 songs like someone hunting for rebound relationship flesh, Cocker says that his now well-publicised split from his wife did not influence the ribald tone of the writing. He might be going through a period of transition, and he might be noticing the aches and pains that accompany being 45 years old, but it's not a midlife crisis album, either.

"I've already had my midlife crisis," he says. "It was a record called This Is Hardcore. I've got that out of way already. I don't think I could have made this record at any other time in my life, and I am a middle-aged person, so it certainly is a midlife record. I just don't see the crisis bit," he laughs. "I think that's just because, unfortunately, around the time the record came out, then it came out that I had split with my wife. But that happened quite a while ago, really. But people like to think, 'oh, yeah, it's a breakup, album.' And they like to put that bit of biographical detail in there, but it's not really true."

Of course, perception often becomes reality, and it seems likely that the more people perpetuate the idea that Further Complications is Cocker's breakup album, the more it will pass into the lore surrounding the album. The temptation is understandable; it's an album begging for some sort of context, the "why" behind its cathartic growl and self-indulgent lust. To that end, Cocker is happy to keep things vague.

"Because I write about emotional things, it's always something that I'm worrying about, how much I'm exploiting relationships and the people in my life for material," he explains. "It's something that you have to be really, really careful with, because it can be really disrespectful to people. That's something between me and my conscious. I can't really go into the reasons why me and my wife split, because it's private... Even though it happened a bit ago, it's still too soon to really deal with that. It just wouldn't feel right to me. The way the record ended up is a combination, or the sound of it, is a combination of deciding to work with a band and maybe the fact that for the first time in my life I felt like I could play a type of rock music authentically or convincingly. The fact that I was 45, maybe I thought, fuck it, because in two years time, I might not be able to do it. As I said at the beginning of the interview, my knee is swelled up."

But, if the album isn't about Cocker, who is it about? Is it really all uncomplicated self gratification? How should we interpret Homewrecker!, an enormous song wrapped in a Stooges-playing-the-Batman-theme groove that warns of a man out on the prowl while his wife and kids are asleep? What should we make of Leftovers, a track whose protagonist admits he's no "eligible bachelor," but who can't keep himself from propositioning a woman with awkward puns? Read deeply, and Further Complications almost sounds like a condemnation of human nature, the kind of thing someone would write if they were feeling responsible for the end of a relationship, hiding pain under self-effacing jokes and skirt-chasing.

"Especially men," Cocker says. "Men are just jerks, aren't they? And men never really grow up. Maybe some do," he says, backtracking a bit." Not all men are jerks. But they're pretty ridiculous, aren't they? Always having to prove themselves, always having to cockfight. Even indie men cockfight. It's still competitive, and I'm part of that. I try to keep a lid on it, but like I say, all those things that are kind of irritating, at least they stop life from being boring. I think that the worst thing, really, is to be bored. That's just a waste of everybody's time. That's a sin. I hope I never bore people."

Jarvis Cocker asks questions but he doesn't really answer them. And the more he talks, the more it becomes clear that he's more interested in the search for the answers to his questions rather than the actual answers themselves. Ultimately, he's asking questions that are even bigger than the function of music or art. He's questioning nothing less than what it means to be human, and Further Complications is his answer, a greasy pimple that indicates that his struggles still lie beneath the skin, even as he moves into his fourth decade of music making.

"I dream of that day when I reach nirvana and all the issues go away, and you stop worrying about stuff and you can cook nice meals for people and they come around and you're the perfect host and you always say the right things," he says, turning sober. "I'd love that, and I aspire to that. I don't want to wallow in my shitness. But it just hasn't happened yet. I want to be good. I want to be a nice person. Please! And that's what I think about it. If I was resigned to being a cunt, I wouldn't bother singing about it, would I? I'd just get on with fucking everybody over. Basically, it's all about the struggle. It's that struggle between different sides of your personality, and once that struggle ceases, you're dead creatively or dead physically. Once people either give in to the dark side or become a Jehovah's Witness, there's no point in listening to the records anymore. Don't you think? It just kind of peters out. What I'm saying, and maybe this is a good conclusion, is that this record is a part of an ongoing process of accepting that struggle and actually revelling in it rather than seeing it as a problem."

Viewed through that lens, Further Complications suddenly becomes a strangely redemptive record, the story of a man who is adjusting to the changing landscape of his life and accepting everything that entails, knee pain and all.

"People expect too much," he says flatly. "They expect to be happy all the time. Well, you can't be happy all the time. That film was good, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. If that treatment existed, would people take it? If you said to somebody, take this pill, and you won't worry about anything or you won't have any bad memories, people probably would take it, because other parts of their life seem like that. People say, 'Get this fridge. You’ll never need to get another fridge again, because it's great.' So you think that maybe your interior emotional life should work like that. But, for me, then what's life for? Surely life is for living and trying to work things out. That's the beauty of it. You live it, and after you live it, you try to unravel it. You learn little bits and you get little insights, and other times you seem to go back. But that's what life is about," he says, sounding heartened by the idea that he has come to the answer to at least one of those questions. "You're just a tourist, and as I once said, everybody hates a tourist."